In late May 2012, conflict erupted in Colquiri, a mining district about 350km south of La Paz. Salaried and cooperative miners who work in different areas of the same mine struggled to control territory. Although the government, salaried workers, and cooperative miners reached an agreement on June 19th, conflict reemerged in September as cooperative and salaried workers continued to fight for control of the richest vein. Tensions flared after cooperative miners killed a salaried miner and injured seven others during a march in La Paz, and Colquiri threatened to be a repeat of an incident in 2006 in Huanuni, Oruro that left sixteen people dead and 115 injured in a conflict over access to the richest veins. The government issued a new decree that divided the mining rights equally between the salaried and cooperative miners, but tensions remain high in Colquiri.

Competition for mining rights

Violent competition for access to mining territory has become increasingly frequent in Bolivia. The government’s closure of hundreds of mines in 1985 and the subsequent privatization of the mining industry throughout the 1990s gave rise to competition between newly formed, private cooperatives and the small number of remaining state-employed, salaried miners. This dramatically changed the dynamics of mining and miners’ political power, there have since been many conflicts over access to resources. (For background see AIN’s 2007 update, “Cooperative Miners in the Nationalization Process: Explosive Politics.”)

Salaried miner during a protest in La Paz; “Cooperativists – pay your taxes!”

Photo credit: Gonzalo Ordóñez

The government mining agency, COMIBOL, and Sinchi Wari, a subsidiary of Swiss corporation Glencore jointly administered Colquiri up until late June. Cooperative miners are independent, artisanal miners whose income comes from the amount of minerals they extract rather than a fixed salary.

At the center of the conflict is the Rosario Vein, believed to be the richest in tin and zinc. However, the government recently admitted its production potential is unknown, since Sinchi Wari took the only documentation when the mine was nationalized.

Violence Erupts Over Rosario Vein

On May 30th, cooperative miners forcefully took over the mine, occupying it until June 8th. In response, salaried miners called for total nationalization. Critics claimed that the government favors the cooperative miners because the incumbent Movement Towards Socialism (MAS) views the cooperativists’ support in the upcoming congressional elections to be more important.

“100% Nationalization of the Colquiri mine for Bolivia now!”

Photo credit: Gonzalo Ordóñez

In June, the government, cooperativists, salaried miners, and Sinchi Wari signed agreements, some of which were contradictory and resulted in blockades, marches, and threats from both cooperative and salaried miners. In rejection of the government’s proposal to grant the most profitable vein to cooperative miners, salaried miners violently retook the mine on June 14th, leaving 22 people injured. Over the next several days, cooperative miners blockaded, marched, and took over another mine operated by Glencore affiliate, Sinchi Wayra.

Cooperative miners refused to relinquish the Rosario vein. On June 19th, the parties finally reached an agreement to nationalize the entire mine, but allowing cooperatives to still continue to exploit designated areas. The government allocated the majority of the Rosario vein to the cooperative miners and left a small portion for the salaried workers.

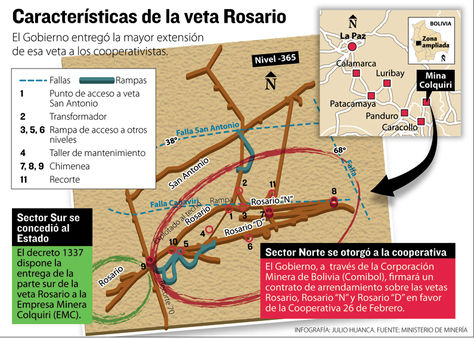

Source: La Razon

Caption: Characteristics of the Rosario Vein

- The government handed over the greater part of the vein to cooperative miners.

- A decree granted the southern sector to state mining company.

- The 26th of February Cooperative obtained the concession for the northern sector.

The agreement failed to satisfy cooperative or salaried miners, and tensions boiled over into another violent confrontation on August 9th. The armed forces confiscated explosives to prevent an escalation of violence.

After a brief period of peace, on August 30th, salaried miners forcefully took over the Rosario vein, demanding a reversal of the June agreement and threatening to detonate explosives and destroy the mine if their conditions were not met. Shortly after, salaried miners went on strike and blocked access to the Colquiri Mine, installing guards around the mountain who threatened to throw dynamite at anyone who tried to pass the blockade.

Throughout September, salaried workers maintained their strike and blockade of the mine while cooperative miners held road blockades countrywide. Both groups staged protests and marches in La Paz. On September 18th, cooperative miners marched to the headquarters of the salaried miners’ union where salaried miners were stationed. A confrontation ensued, and cooperative miners launched dynamite at the salaried miners, killing one and injuring at least seven more.

Salaried miner protest with the Bolivian Workers Central in La Paz

Photo credit: Gonzalo Ordóñez

Salaried miners retaliated in Colquiri by taking over cooperative facilities, blocking the entrance to the cooperative sections of the mine, burning two vehicles that belong to cooperative leaders, and threatening cooperative miners and their families. Families of salaried miners also joined the retaliation.

Government Response

As per usual in these types of conflict, the government’s reaction was tardy. After the death of the salaried miner, the government sent some 500 police officers to the area. Police confiscated dynamite from both cooperative and salaried miners on multiple occasions, including once when cooperative miners tried to transport dynamite in an ambulance to use in a march. Although the government responded late, it seems that government involvement may have helped avoid further violence; shortly after the death of the salaried miner in La Paz, cooperative miners arrived with eight buses of people, and salaried miners prepared to “resist the incursion,” but ultimately the cooperative miners decided against initiating a confrontation.

In the following weeks, there was strained dialogue between the government and both parties. Cooperative miners from other areas joined the Colquiri cooperativists in installing blockades around the entire country. The Bolivian Workers Central, the main union in Bolivia to which salaried miners belong, initiated a 72-hour strike in solidarity with the miners.

Salaried miner protest with the Bolivian Workers Central in La Paz

Photo credit: Gonzalo Ordóñez

In response to the death of the salaried miner, the government passed a decree criminalizing the possession and use of dynamite in protests.

On October 3rd, the government passed Supreme Decree 1368, which demarcated the zones of work for salaried and cooperative miners in the Rosario Vein and expanded the area miners are allowed to work.

For now, the conflict seems to have subsided. However, with such tension between both groups who are working in close quarters, it is likely reemerge.