Link to .pdf version of the memo

Bolivian Drug Control efforts:

Genuine Progress, Daunting Challenges

By Kathryn Ledebur and Coletta A. Youngers

Introduction

Following a landslide victory at the polls, Evo Morales became president of Bolivia in January 2006.[i] Head of the coca-growers’ federation, Morales was a long-standing foe of U.S. drug policy, and many observers anticipated a complete break in U.S.-Bolivian relations and hence an end to drug policy cooperation. Instead, both Morales and the George W. Bush administration initially kept the rhetoric at bay and developed an amicable enough bilateral relationship—though one that at times has been fraught with tension. Following Bolivia’s expulsion in 2008 of the U.S. Ambassador, Philip Goldberg, for allegedly meddling in the country’s internal affairs and encouraging civil unrest, and the subsequent expulsion of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), the White House upped its criticism of the Bolivian government and for the past five years has issued a “determination” that Bolivia has “failed demonstrably during the previous 12 months to adhere to [its] obligations under international narcotics agreements.”[ii] U.S. economic assistance for Bolivian drug control programs has slowed to a trickle. Nonetheless, in 2011 the two countries signed a new framework agreement to guide bilateral relations and are pending an exchange of ambassadors. Moreover, cooperation continues between the primary Bolivian drug control agency—the Ministry of Government’s Vice Ministry of Social Defense and Controlled Substances—and the Narcotics Affairs Section (NAS) of the U.S. embassy.

At the international level, Bolivia is seeking to reconcile its new constitution, which recognizes the right to use the coca leaf for traditional and legal purposes and recognizes coca as part of the country’s national heritage, with its commitments to international conventions. In June 2011, the country denounced the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs as amended by the 1972 Protocol and announced its intention to re-accede with a reservation allowing for the traditional use of the coca leaf. (The 1961 Convention mistakenly classifies coca as a dangerous narcotic, along with cocaine.) Unless more than one-third of UN member states object by the January 10, 2013 deadline, the Bolivian reservation will be accepted and the country will once again be a full Party to the Single Convention.

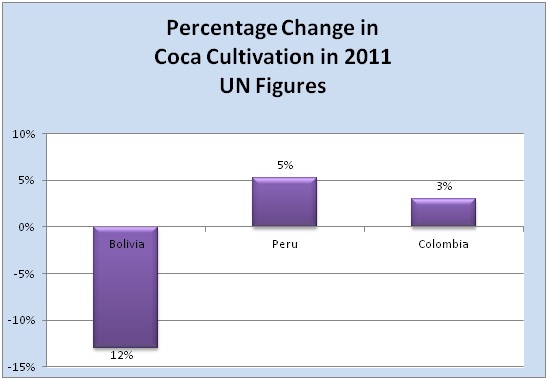

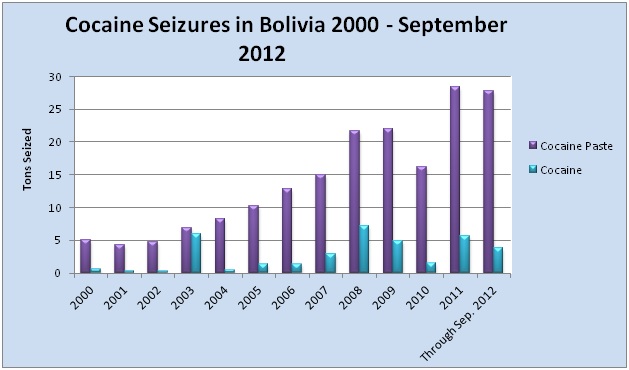

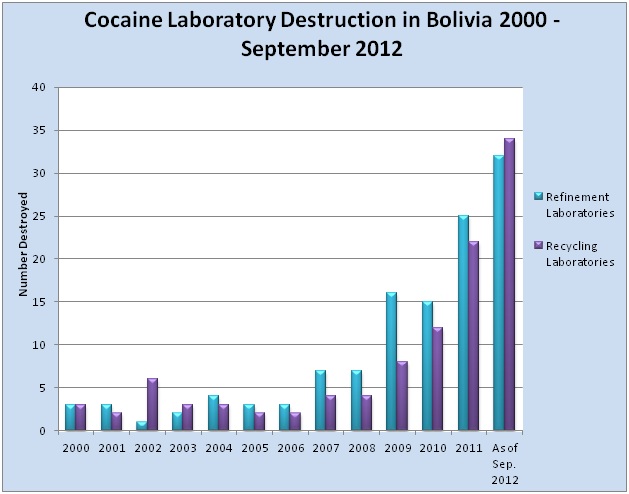

The approaching date for Bolivia’s potential return to the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs provides an opportune moment to evaluate the Bolivian government’s progress achieving its drug policy objectives. Moreover, the Morales administration has been in office for nearly six years, providing a clear track record to evaluate. Adopting a “coca yes, cocaine no” approach, Bolivia has sought to decrease the cultivation of coca—the raw material used in manufacturing cocaine—while increasing actions against cocaine production and drug trafficking organizations. In 2011, the land area devoted to coca cultivation in Bolivia dropped by 13 percent, according to U.S. government figures, in contrast to net increases in Peru and Colombia. Seizures of coca paste and cocaine and destruction of drug laboratories have steadily increased since President Morales took office. Yet despite the positive results achieved to date, the government faces increasing challenges as the amount of coca paste and cocaine flowing across its borders from Peru has increased, the production of cocaine in Bolivia itself has risen, and drug traffickers have diversified and expanded areas of production and transportation within the country.

The Bolivian government has made significant progress facing the ongoing challenges of drug production and trafficking, in part due to the assistance provided by the European Union (EU), the United States, and others. The U.S. government should now recognize this progress in its annual determinations. The string of negative determinations are increasingly disconnected from reality in Bolivia and retain little credibility with the Bolivian government or with other governments in the region, which continue to see the annual U.S. rating as offensive and politically motivated. The signing of the framework agreement marked significant progress in U.S.-Bolivian bilateral relations. Both governments should build on that success by using the accord as a venue to discuss areas of concern, friction, and consensus. While differences will undoubtedly arise, it is in the best interests of both countries to maintain an open dialogue.

Coca Cultivation

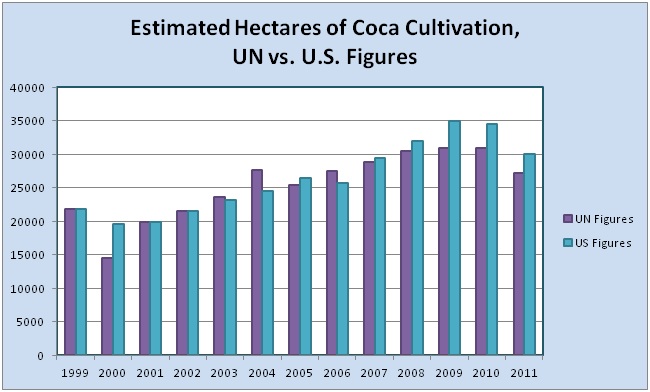

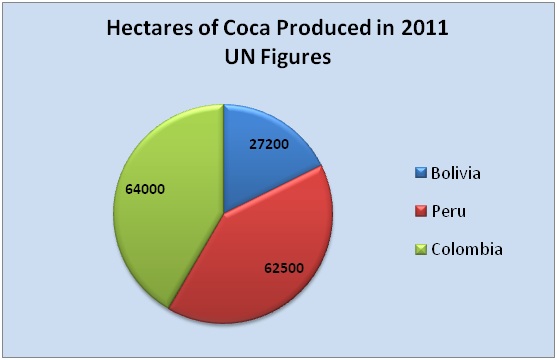

In September 2012, both the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and the U.S. government released their 2011 statistics on coca cultivation in Bolivia. The UN and U.S. estimates differed by only one percent (in stark contrast to statistics produced for other countries). The convergence of the coca cultivation estimates points to the effectiveness of the government’s coca crop monitoring strategy, which benefits from coca grower cooperation, a more concentrated coca crop, and technological advances in measuring cultivation. In short, the monitoring system in place allows for a far more accurate measurement than is the case with either Peru or Colombia, the primary producers of coca for the illicit market. (According to the UNODC, in 2011 Colombia cultivated 64,000 hectares of coca and Peru 62,500 hectares, representing three and five percent increases, respectively.) It also provides the Bolivian government and the international community with an opportunity to develop collaborative policies based on reliable information about coca trends.

Source: UN Crop Monitoring Reports

Source: UN Crop Monitoring Reports

Source: UN Crop Monitoring Reports

The UNODC’s 2011 Coca Cultivation Survey,[iii] released on September 17, 2012, indicates that coca cultivation in Bolivia fell to 27,200 hectares[iv] in 2011 from 31,000 hectares in 2010—a 12 percent decrease. The report notes that coca cultivation declined in every important coca-growing region in the country, bringing the overall area under cultivation to near the 2005 level. The UN attributes this “significant” decrease to “effective control” through cooperative coca reduction and eradication. The UN also reports a 13 percent reduction in overall coca leaf yields, down to 48,100 metric tons in 2011 from 55,500 metric tons in 2010. According to the head of the UNODC office in Bolivia, César Guedes, “The progress in Bolivia is undeniable. This year, Bolivia is the only country with a decrease in coca cultivation … The facts are sufficiently clear, not only with regards to coca cultivation but also with a long list of verifiable successes.”[v]

Similarly, the White House’s September 14 determination reports that the 2011 U.S. government coca cultivation estimate for Bolivia was 30,000 hectares, a 13 percent decrease in Bolivia’s coca crop.[vi] In a July 2012 interview, the U.S. Embassy in Bolivia’s Chargé d’Affaires, John Creamer, stated that there had been an “impressive net reduction in the number of hectares of coca in 2010 and 2011.”[vii] Nonetheless, the September determination—which concludes that Bolivia has “failed demonstrably during the previous 12 months to adhere to [its] obligations under international narcotics agreements”—downplays the significance of the coca reduction, referring to the 13 percent decrease as only “slightly lower” than the 2010 estimate of 34,500 hectares.

Source: UN Crop Monitoring Reports and U.S. International Narcotics Control Strategy Reports

Cooperative Coca Reduction and Social Control Begin to Show Results

The success of the Morales administration’s cooperative coca reduction strategy hinges on the voluntary participation of farmers from all coca-growing regions in the country and on balancing pressures from the international community with the demands of its coca-growing constituents. Successful collaboration between Bolivian authorities and those of neighboring countries, notably Brazil, and with international organizations and foreign donors has also contributed to improving the effectiveness of the monitoring effort.

Bolivia’s cooperative coca reduction strategy allows each Chapare farmer to grow one cato of coca,[viii] continuing a policy adopted by the Carlos Mesa government in 2004. Any coca grown beyond that is subject to elimination. The Bolivian government has expanded this approach into areas of the country, such as parts of the La Paz Yungas, where no significant coca eradication had previously occurred. As a result of the cato agreement, the violence and conflict generated by forced eradication in the Chapare has, with rare exceptions, ceased. It also was initially successful in stabilizing coca cultivation and 2011 marks the beginning of what Felipe Caceres, Bolivia’s Vice Minister of Social Defense and Controlled Substances, expects to be a sustained downward trend in coca cultivation.[ix]

Photo: Sara Shahriari

The relative success of the policy stems, in part, from the coca growers federations’ ability to enforce the agreement.[x] In turn, limited production maintains a stable and relatively high price for coca, a guaranteed subsistence base, and freedom from the repression that accompanied forced eradication. According to the UNODC 2011 report, the price for coca in the legal and illegal markets is the same, providing little comparative incentive to deviate from legal sales. The secure income generated from the cato of coca also allows for experimentation with other income-generating activities with complementary implementation of economic development programs through the National Alternative Development fund (Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Alternativo, FONADAL) and other programs that offer additional sources of income, often referred to as “integrated development with coca” (see below). Finally, the sanctions imposed by the federations for failure to comply with the one cato limit are severe, including the loss of the right to grow coca and, ultimately, land expropriation for repeat offenders.

As explained by federation leader Rolando Vargas, there is a two-pronged strategy for coca control: “the internal control of the union and state control,” which includes aerial surveillance and elimination of coca that is grown in violation of the cato agreement.[xi] According to Vice Minister Caceres, during the first year of the Morales government, 150 coca farmers lost their right to grow coca for one year. From January to September 2012, the number rose to 600 farmers.[xii] A second offense results in the permanent loss of coca growing privileges. To enforce this—or in cases where coca is grown in areas not covered by the cato agreement—the Bolivian government has formed the Grupo Surazo (named after a biting cold front that quickly descends in tropical regions), an elite military unit of the Joint Task Force that enters communities without warning and forcibly eradicates excess or unpermitted coca. However, the new units’ modus operandi raises concerns about the potential for abuses, particularly mistreatment of the communities affected, of the kind that characterized the past forced eradication campaigns.

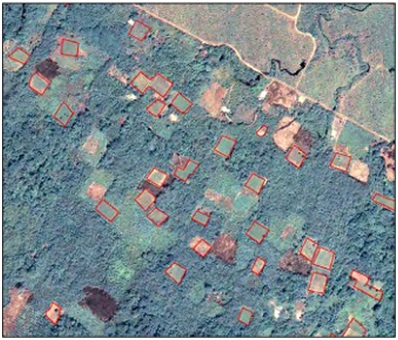

UNODC satellite imagery clearly delineates catos of coca in the Chapare

Finally, the Morales government has consistently met its annual coca reduction targets. According to the Vice Ministry of Social Defense and Controlled Substances, as of mid-November 2012, 10,201 hectares had been eliminated. The goal for 2012 is a reduction of 11,000 hectares.

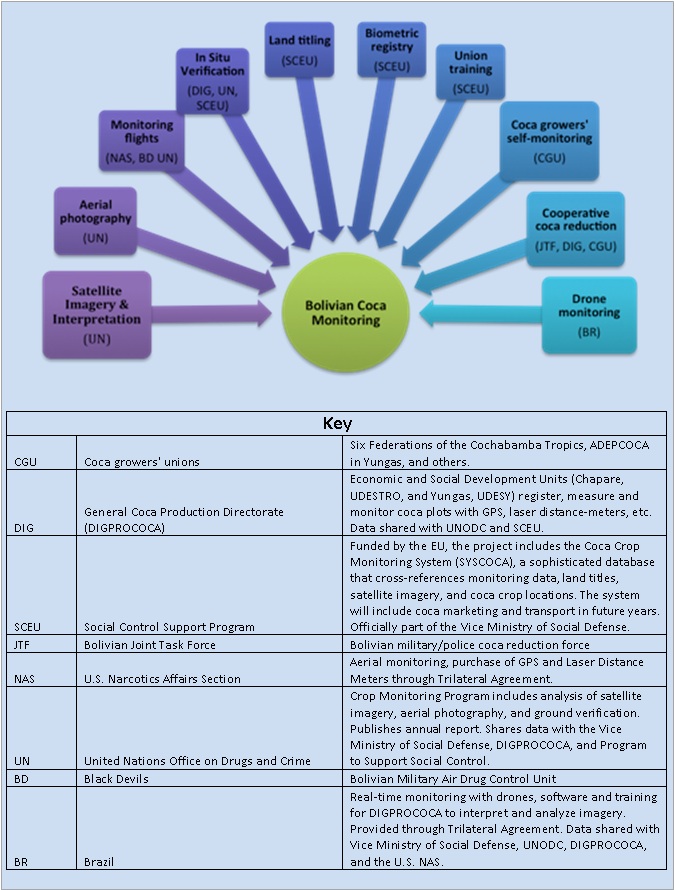

Coca Monitoring from Fields to Markets

The heart of these efforts is the coca monitoring strategy itself, which is carried out collaboratively by Bolivian state institutions. Bolivian cross-referenced coca monitoring is a unique model incorporating the active, voluntary participation and engagement of coca farmers with state institutions, as well as information sharing and engagement with international entities and agencies, including the United Nations, the European Union, the United States, and Brazil. The General Coca Production Directorate (Dirección General De Desarrollo Integral De Las Regiones Productoras De Coca, DIGPROCOCA) registers the catos and provides farmers with land titles. That registry is part of a sophisticated database, SYSCOCA, which cross-references the information with satellite images, aerial photography, en situ inspections, and measurements with GPS and laser distance meters and recently updated land tenure information. This information is then used to plan cooperative coca reduction. SYSCOCA is part of the EU-funded Coca Social Control Support Program, and the database is also shared with the UNODC’s Coca Monitoring Project. Most coca plots are monitored several times a year by satellite, ground verification by three different offices, and with aerial photography.

As a part of the monitoring effort, the EU has funded a biometric registry of coca producers, each of whom is to receive his or her own personal identification card. The registry of over 48,000[xiii] producers has been completed and the ID cards, which contain an electronic chip to facilitate government control, will be distributed to each authorized farmer. The SYSCOCA database described above provides Bolivian government officials with up-to-date information on the precise amount of coca planted, to whom it belongs, and whether it complies with national law. Through the electronic ID and the information obtained in the registry, government officials will be able to trace the harvest of the coca leaf and its sale in the legal local market. The idea is that government authorities will then be able to trace coca that had been diverted from the legal market with greater efficiency and will be able to determine who is not selling their coca to legal markets. [xiv]

Of particular significance, the Bolivian government plans to extend the biometric registry, with EU support, to control the transit, sale, and marketing of the coca leaf, from the field to the consumer. Social Control Support Program officials have already overcome what was potentially the most significant impediment to this system: the consent of coca farmers. The farmers have agreed, primarily because the registry validates their right to the cato. Eventually, anyone involved in the legal transportation or sale of coca will have an identification card and will thereby be entered into the system. Then the government will be able to monitor the transportation of coca by registered intermediaries to the two authorized wholesale markets and its distribution to individual vendors, all through the scanning of their respective biometric identification cards. When fully implemented, the system, which requires the technological equivalent of a smart phone, will represent a dramatic improvement over the current paper records, where registered merchants have stamped forms that allow them to transport coca. In contrast, the biometric registry will allow for more complete and rapid information sharing.

No system is foolproof and multiple obstacles still stand in the way of the effective implementation of the monitoring program, as drug traffickers are adept at adapting to new technological challenges, and corruption could undermine the effort, with opportunities for diversion to the illicit market all along the way. Nonetheless, it represents a pragmatic, ambitious, and potentially viable effort to control the diversion of coca to illicit markets. If successfully implemented, this effort will arguably provide the most precise coca monitoring system available in the region.

Economic Development in the Chapare

The success of coca reduction efforts depends in large part on the ability of coca farmers to diversify their sources of income. In the case of the Chapare coca-growing region, efforts are underway to improve the overall quality of life of the local population. Concrete data is hard to come by, but there are signs that farmers are taking advantage of a range of income-generating opportunities. The UNODC points to significant agricultural diversification in the core area of the Chapare region (excluding national parks) where cooperative reduction has been implemented since late 2004. According to its 2011 coca monitoring survey, bananas covered the largest area cultivated in the Chapare, followed by citrus fruit and palm hearts, and then coca. UNODC attributed this phenomenon to sustained, integrated development efforts.[xv] But it is also important to note that the guaranteed subsistence income provided by the small parcel of permitted coca also allows farmers to take risks with other crops.[xvi] A June 2012 report by the U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) came to a similar conclusion, noting that “USAID’s activities in Bolivia have contributed to improved poverty indicators, and hectares of principal alternative crops—such as bananas and citrus—have increased more than coca.”[xvii]

In interviews conducted by AIN and WOLA in late September 2012, Chapare municipal and national government officials, coca growers, and representatives of international organizations all agreed that the overall quality of life in the Chapare has improved due to increased government investment in education and health, and improved transportation. A generation of children of Chapare coca growers has now graduated from local universities, returning to the area with a range of technical skills to offer. Banana exports to Argentina have become a mainstay of the local economy and, in addition to the crops listed above, farmers are investing more in products such as honey, coffee, and chocolate, and some are investing in cattle. Others are getting involved in small-scale businesses, such as marketing or transportation services. As one female coca grower told AIN and WOLA, “We don’t want to be dependent on coca. That is why it is mandatory for members of our union to grow other things.”[xviii]

According to the mayor of Shinahota, Rimer Agreda, one of the most important advances in the region is the improvement in basic services, particularly transportation. “We now have roads and bridges to about 80 percent of the zone,” which allows for the transportation of other agricultural products. “Now many people have their cato, but they are also exporting bananas and driving a truck too.” Such economic diversification appears to be slowly increasing local incomes, though documentation as to how much is not available. Agreda also points out, however, that it is also the case that coca growers “are now accustomed to having their cato of coca.”[xix]

The Morales administration has also promoted the development of licit uses of the coca leaf as a means of generating additional income. The industrialization of the coca leaf is probably the weakest pillar in the Morales strategy, yet some advances have been made. Several years behind schedule, a coca-processing plant began operations in the Chapare in late 2011.The high price of coca, combined with difficulties in obtaining organic coca (which is required for every product), have slowed productivity. Dealing with the very high humidity in the zone also presents a challenge, as food products quickly go stale. Nonetheless, the factory has begun to manufacture a variety of products, including coca “chips” for the subsidized public school breakfast program, coca liquor, energy drinks, flour, ointments, and coca holiday cakes. When WOLA and AIN staff visited the plant in late September 2012, production had paused for a week so the machinery could be cleaned, but we were able to meet with the two technicians who run the plant. They said that about thirty local people are employed at the plant and that they are presently filling orders as they come in, with the hopes of moving to full-scale production over time.

Beyond the Chapare

For many years, coca production it the Chapare region far exceeded that in La Paz Yungas. But the success of cooperative coca reduction in the Chapare has meant that the Yungas is now the country’s largest coca producing region, with 67 percent of the national crop.[xx] Prior administrations were unable to reduce excess coca planting in this region, but the Morales administration has initiated reductions through extensive negotiation and integrated development efforts, which seek to complement income provided by coca. Beginning in 2006, FONADAL—with funding from both the Bolivian national treasury and from the EU—has implemented hundreds of infrastructure, economic development, institutional strengthening, and social development projects, primarily in coca-producing zones, with an emphasis on consultation with the participating families and food security.[xxi] Launching these participatory development initiatives before negotiating coca reduction has helped the Morales administration reach agreements in spillover zones, implement the cato system in the Yungas,[xxii] and establish coca production ceilings for Yungas sub-regions. These factors largely explain the 11 percent reduction in coca cultivation in the Yungas in 2011 reported by the UNODC. Furthermore, for the first time, farmers within the traditional coca-growing zone of the Yungas have agreed to work with the Bolivian government to limit their production, although difficulties remain.[xxiii]

According to the UNODC, in 2011 coca cultivation declined in all coca-growing regions, including national parks (resulting in the nationwide 12 percent decrease noted earlier). In the Yungas, there was an 11 percent decrease, Apolo-Norte de La Paz, seven percent, and the Chapare, 15 percent. National parks also saw a 15 percent reduction, resulting from forced eradication. Nonetheless, the UNODC data show that cooperative coca reduction through social control is the driving force behind declining coca cultivation.

Still, the government faces the challenge of the continuing spread of coca into new areas, including national parks. According to UNODC estimates, between 2010 and 2011, there was a 30% increase in the price of coca leaf in authorized markets and a 16% increase in unauthorized markets.[xxiv] The significant price increases have led to coca planting in new regions, as people plant coca or migrate to new areas and plant as a means of generating family income. For example, coca reduction occurred for the first time in November in the Ayopaya Province of Cochabamba, where no coca had been previously detected.[xxv]

The Morales administration implemented forced eradication in the Isiboro Secure National Park Indigenous territory (El Territorio Indígena y Parque Nacional Isiboro-Secure, TIPNIS) in an effort to allay fears that the hotly contested highway planned through the region could provoke an explosion of coca and cocaine production there. This scenario is improbable. Settlers in the TIPNIS plant coca as a result of poor road infrastructure and access to markets for other crops, and traffickers already thrive in areas like TIPNIS with multiple waterways flowing toward Brazil. The road would clearly provide greater access for drug control efforts, but is highly criticized as it will provoke severe environmental damage and open the region to commercial agriculture and trade.

Efforts to Disrupt Drug Trafficking

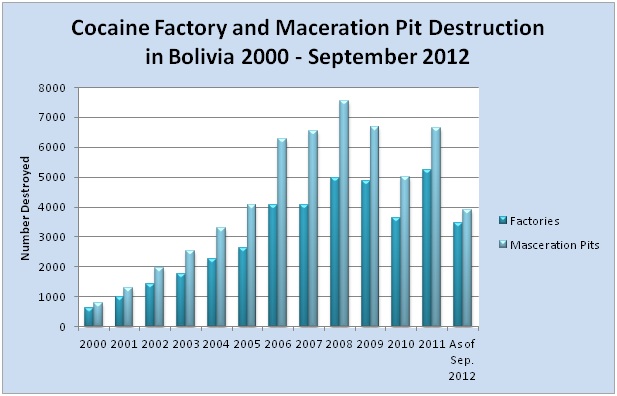

Even though coca production declined significantly in 2011, the Bolivian government confronts a growing drug trade in the country. The government’s stated political will and increased enforcement efforts have led to a steady increase in seizures of coca pasta and cocaine, as well as destruction of “laboratories”—mostly small-scale production sites—since the Morales administration took office in 2006. According to the EU’s Nicolaus Hansmann, going after the drug trade is “one of the top priorities of the government as they know that both internally and externally, the worst damage that they can do to [the Movement for Socialism party, MAS] is to associate it with drug trafficking.”[xxvi] Bolivian Foreign Minister David Choquehuanca emphatically states that “we are fully committed to the fight against drug trafficking … which threatens our children and grandchildren.”

Source: Vice-Ministry of Social Defense and Controlled Substances of Bolivia and Special Force against Drug Trafficking (FELCN)

Source: Vice-Ministry of Social Defense and Controlled Substances of Bolivia and FELCN

Bolivian authorities have repeatedly expressed concern about the presence of representatives of international drug trafficking organizations in the country, something they attribute to Bolivia’s central location in the continent, easy access to the corridor through Argentina and on to West Africa (now a major transshipment point for illicit drugs en route to Europe and other parts of the world), and proximity to the second largest cocaine market in the world, Brazil. In addition, Bolivia offers comparatively low operating costs due to significant fuel subsidies and the absence of sustained violence associated with drug trafficking in Mexico and Colombia. “Let’s face it,” notes police Colonel Gonzalo Quezada, “we’re strategically located for traffickers and Bolivia is a nice place to work without getting killed for emissaries from cartels who want to explore their options; but that doesn’t mean that we aren’t doing everything we can to stop them.”[xxvii] He claims that four Colombian drug trafficking groups have sent people to Bolivia; however, other nationalities are represented as well. Drug trafficking detention statistics confirm these dynamics. From January to September 2012, Bolivian police arrested people from 30 different countries.

Until the late 1990s, elite, geographically-concentrated families dominated drug trafficking in Bolivia. However, in recent years trafficking networks have diversified, tend to concentrate on one part of the drug trafficking chain and have spread throughout the country. The great bulk of drug production and trafficking in Bolivia is now carried out by small family “clans,” none of which has a significant share of the market. They can be broken down into four different groups: those who buy coca for illicit purposes; those who buy precursors; others who provide the labor and temporary infrastructure for making coca paste (maceration pits for making coca paste have become a thing of the past, as traffickers have adopted the easier “Colombian method” whereby the coca is ground up with weed whackers); and those who transport it to cocaine laboratories or across the border into Brazil where it is used for making paco, a highly-addictive cocaine derivative. [xxviii] The arrest and disbanding of one group makes a negligible dent, if any, in the drug trade as it is quickly and easily replaced.

Source: Vice-Ministry of Social Defense and Controlled Substances of Bolivia and FELCN

The influx of coca paste and cocaine from neighboring Peru poses another major challenge faced for Bolivian authorities; according to Col. Quezada, approximately half of the coca paste and cocaine seized in the country originates in Peru. As the price of a kilo of coca paste is US$200 higher in Bolivia than Peru, more and more cocaine paste is being brought from Peru into Bolivia. Bolivian police investigations show that most of the influx is coming from the VRAE region of Peru (now referred to as the VRAEM by the Peruvian government). While most is brought in to the country in smaller quantities by “mules,” or small-scale traffickers, it is also being transported by small airplanes into Bolivian territory for processing and then sent on to Brazil. This is a particular concern of the Bolivian police given the country’s very limited capacity to control the country’s airspace.

The U.S. government claims the expulsion of the DEA, which left Bolivia in January 2009, permanently impeded Bolivia’s ability to deal with drug trafficking, generating debate about the Morales administration’s political will to implement effective drug control policies. Other international officials are more supportive of Bolivia’s determination to address the problem. As noted by the EU’s Hansmann, there is a “great will [by Bolivian officials] to move forward on drug control policy … but this doesn’t necessarily conform to what the United States wants.” He also points out that the U.S. focus on eradicating coca has been detrimental to broader drug control efforts: “The rest was crippled, there is no experience, institutional reforms did not happen, they failed to pass good legislation.”[xxix]

The FELCN’s Col. Quezada agrees that institutional strengthening and a range of new laws are needed to strengthen the hand of enforcement in dealing with the drug trade. He also points out that his top priority right now is “not at the international level, but the domestic arena.” As the drug trade has expanded in Bolivia, so has micro-trafficking and other small-scale operations now found in communities around the country. “We are focused on operations that protect our citizens.”[xxx] The institutional challenges, however, remain formidable as Bolivia faces severe budget limitations and limited technical capacity in dealing with a complex criminal enterprise with virtually unlimited funds.

With the DEA’s departure, Bolivia has begun to work closely with its neighbors on a range of drug control initiatives and has signed bilateral agreements with Brazil, Peru, Argentina, Paraguay, Colombia, and others. Brazil is probably Bolivia’s most visible partner in drug control; the two countries have had frequent bilateral talks, have signed multiple agreements to strengthen border control, and Brazilian drones are used to identify cocaine paste production sites.[xxxi] The joint militarization of the shared border could, however, provide more challenges than successes. Longer than the U.S.-Mexican border and much less monitored, physically blocking the flow of drugs is impossible. At the same time, the border is not well defined and Brazilian troops have crossed over into Bolivian territory. As a result, the increased military presence along the border has at times fueled bilateral tensions.[xxxii]

Bolivia also signed two important trilateral accords: one with Brazil and the United States to support coca cultivation monitoring, and one with Brazil and Peru on border controls and interdiction. Most recently, on November 13, 2012, the Bolivian, Brazilian, and Peruvian governments formed a permanent working group to systematize drug control efforts and to develop protocols to secure the countries’ airspace in an effort to address the problem of over-flights described above. The plan includes the placement of radar on the nations’ borders in order to be able to shoot down flights identified as transporting illicit drugs.[xxxiii] Unfortunately, past shoot-down policies in other countries have been fraught with problems and have led to the deaths of innocent civilians.[xxxiv] Also of note, on November 25, 2012, the Brazilian military signed a $420 million contract for the first phase of the Integrated Border Surveillance System, including radar, drones, and sensors to be initially put into place along the border between Bolivia and Paraguay.[xxxv]

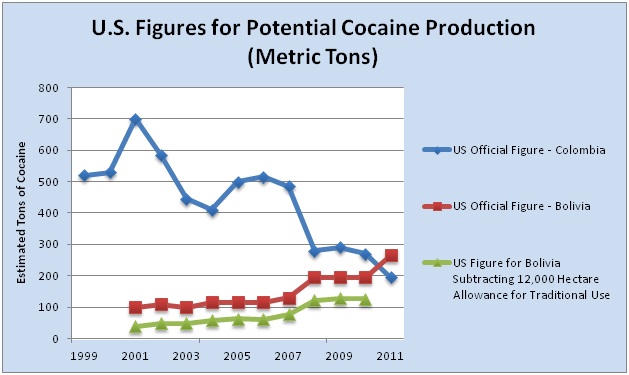

Varying Estimates of Potential Cocaine Production

Estimates of potential cocaine production are arguably a more important measure of the size of a country’s illicit production and trafficking than are estimates of the land under coca cultivation. Wide discrepancies between the UN and U.S. in cocaine production estimates in Bolivia—and a lack of transparency regarding U.S. estimation methods—have led to contention over how much cocaine is likely being produced in Bolivia. Despite reporting that the land devoted to coca cultivation has diminished in 2010 and again in 2011, in September 2012 the U.S. government announced a stunning increase in Bolivia’s potential cocaine production: from an estimated 195 metric tons, which held steady from 2008 to 2010, to a potential production of 265 metric tons for 2011. In other words, even with the U.S.-estimated 13 percent reduction in coca hectares and the 13 percent decline in coca leaf yield reported by the UN, the U.S. government asserted that Bolivia’s potential cocaine production increased by 36 percent. For its part, the Bolivian government estimates that approximately 80 metric tons could be produced in the country.

WOLA Senior Associate for Regional Security Policy Adam Isacson has calculated that 265 metric tons of cocaine from 30,000 hectares of coca amounts to an astonishing 8.83 kilograms of cocaine per hectare of coca, in stark contrast to Colombia where U.S. data shows 2.70 kilograms per hectare.[xxxvi] In other words, the U.S. figures imply that Bolivian coca leaf is yielding three times more cocaine than Colombian coca leaf. (Given that a sizable proportion of Bolivia’s coca yield is produced for traditional, legal purposes—12,000 hectares according to present Bolivian law—the coca-to-cocaine conversion ratio implied by the U.S. figures is even higher.) The U.S. government estimates that the amount of potential cocaine production in Colombia fell between 2010 and 2011 by 25 percent, from 270 to 195 metric tons. By contrast, the UN calculated Colombia’s potential cocaine production at 345 metric tons for 2011, using U.S. government data for the conversion from paste to cocaine.

Source: U.S. International Narcotics Control Strategy Reports

U.S. officials maintain that the increase in potential cocaine production in Bolivia is due to more efficient processing methods (ironically, the same methods used in Colombia) and to the maturity of existing fields, which contribute to higher yields. All agree that more cocaine can be produced with less coca in Bolivia today. Yet that would be unlikely to account for such a dramatic increase in potential production. Furthermore, the U.S. government announced a 50 percent increase in its estimates of Bolivia’s potential cocaine production in 2008, using the same argument—more efficient cocaine processing methods.[xxxvii] In short, U.S. officials claim that potential cocaine production more than doubled in three years, despite reductions in coca cultivation, each time pointing to the adoption of Colombian processing methods. Most disturbingly, the U.S. government provides no information whatsoever about how they derive these statistics, giving credence to allegations that the numbers are constructed for political purposes.

U.S. officials do say that Operation Breakthrough, initiated in Bolivia in 1993, provides the baseline methodology to calculate potential cocaine production in the Andes. (AIN was able to obtain the Operation Breakthrough methodology via a declassified DEA document.)[xxxviii] Yet current estimates, which reportedly continue to employ these methods, demonstrate some dramatic contradictions. First, Operation Breakthrough estimated in 2000 that the “Colombian cocaine processing method” is approximately 25 percent more effective than the maceration pit systems initially used in Peru and Bolivia.[xxxix] In addition, Operation Breakthrough identified “critical elements to estimate cocaine production”:

1) number of hectares under cultivation;

2) the coca leaf yield per hectare;

3) the coca leaf alkaloid content within the leaf;

4) the efficiency with which the cocaine alkaloid in the leaf is converted into cocaine base; and

5) the efficiency with which cocaine base is converted into cocaine hydrochloride (HCL) [xl]

The study provided the following formula:

mature coca leaf cultivation X coca leaf yield X cocaine alkaloid content X laboratory efficiency = cocaine base (MT)[xli]

Yet U.S officials acknowledge that they are presently unable to determine coca leaf yields and have no data to calculate the efficiency of the alkaloid extraction, both indispensable to calculate potential cocaine production. The U.S. government complained in March 2012 that they have been unable to carry out yield studies in Bolivia since the expulsion of the DEA in January 2009.[xlii] In other words, U.S. officials do not have the basic information needed to calculate potential cocaine production in Bolivia via the Operation Breakthrough methodology.

The UNODC’s 2011 coca cultivation report on Bolivia did not provide any data on potential cocaine production, although they reported a 13 percent decrease in coca yields, which would suggest a reduction, rather than an increase, in potential cocaine production. Concerns that the previous methodology is out of date and may not produce accurate statistics led the UNODC to revamp its data collection and analysis. The organization developed a new methodology, which includes gathering information from incarcerated drug traffickers to determine cocaine-manufacturing methods in order to replicate them in different areas to estimate coca yields and potential cocaine production. This will both improve statistics at the national level and facilitate comparisons between countries. The new methodology is already being implemented in Peru and Colombia, and in September 2012 the UNODC and Bolivia signed an agreement to allow its implementation in Bolivia. The UNODC hopes to release the new data in mid-2013.[xliii] Calculating potential cocaine production is always a challenging task. In Bolivia alone, there are at least eight ecosystems that will lead to different coca yields. However, the new methodology developed by UNODC, if implemented accurately and completely, offers the possibility for more reliable, transparent, and credible statistics on potential cocaine production.

U.S. Policy toward Bolivia

The debate sparked by the White House’s September 2012 “determination,” and in particular its claims regarding potential cocaine production in Bolivia, has strained what has been fairly steady bilateral collaboration on drug control programs. Despite the expulsion of the DEA, the Bolivian Ministry of Government’s Vice Ministry of Social Defense and Controlled Substances and the U.S. embassy’s Narcotics Affairs Section (NAS) maintain daily cooperation on the ground. In October 2011, Assistant Secretary of State for International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs William Brownfield told a congressional committee:

In Bolivia, eradication efforts are a highlight of a sometimes-difficult bilateral relationship and actually exceeded the 2010 target of 8,000 hectares. These efforts appear to have stopped the expansion of coca cultivation … Furthermore the U.S. estimate actually showed a 500-hectare decrease in land under coca cultivation. In Bolivia, U.S. assistance, including support for training and canine programs, has resulted in Bolivian seizures of coca leaf that are 19 times higher than they were a decade ago.[xliv]

The NAS continues to fund drug and coca control efforts—albeit with a reduced budget—and coordinates with the Bolivian government on a daily basis. U.S. Chargé de Affaires John Creamer[xlv] confirmed on July 15, 2012 that despite rumors to the contrary, “NAS is staying … [Its] mission is changing as a result of the Bolivian’s government’s nationalization of the drug war, an initiative we welcome … so we are approving less operating costs and emphasizing training more.”

A framework agreement that formally renewed bilateral relations was signed in November 2011 and the governments announced their intention to reinstate ambassadors. Although since that time both countries have reiterated this point, it is unclear how long this process will take (and even after the U.S. government announces a candidate for the post, significant delays in the U.S. Senate’s confirmation process could occur). The framework agreement includes recurring dialogue on drug policy. In January 2012, Bolivia, Brazil, and the United States signed a trilateral coca cultivation monitoring agreement. At the 2012 Summit of the Americas, President Obama observed, “The recent agreement between the U.S., Brazil, and Bolivia to go after (excess) coca cultivation in Bolivia is the kind of collaboration we need.”[xlvi]

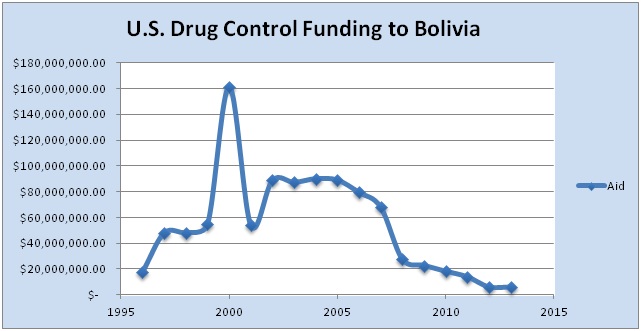

U.S. economic assistance to Bolivia has declined steadily since President Morales came into office. This is largely due to overall budget cuts, vocal opposition on the part of key Republican members of Congress to Morales’ relationship with Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez and Cuba’s Raul Castro, and in protest of the expulsion of the DEA. However, from the Bolivian government’s point of view, less aid is better than more aid with strings attached. As noted by Foreign Minister Choquehuanca, “We want to have good relations with all countries. But relations based on respect. I have found understanding in the United States. We are not afraid of the United States as previous governments were. We are a small country, but one with dignity.” He concluded that comprehension of the situation in Bolivia on the part of some U.S. officials is what allowed for the signing of a framework agreement based on “mutual respect,” adding, “We would rather have good relations without economic assistance than economic assistance whose use is dictated by the United States.”[xlvii]

Source: U.S. International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) reports via Just the Facts.

However, two issues in particular have put significant strain on the bilateral relationship. The continuation of the unilateral U.S. drug control “determination” (previously called “certification”)—in which the United States judges which countries are effectively meeting international drug control obligations—is widely criticized across Latin America, further eroding U.S. credibility in a region now openly questioning the prevailing drug policy paradigm. The Obama administration has continued the practice of its predecessor of giving Bolivia a failing grade (along with Venezuela and Myanmar) each September. However, in the case of Bolivia, the numerous errors and inaccuracies—particularly evident in the 2012 determination—give the impression that the decision is based on political motivations rather than an accurate assessment of drug control efforts on the ground. For example, the 2012 determination stated that the UNODC had reported a slight increase in coca cultivation in 2011, when in fact three days later the UNODC announced a 12 percent decrease. It also asserted that “Bolivia remains one of the world’s largest producers of coca leaf for cocaine and other illegal products.” As noted previously, Bolivia’s coca crop is significantly smaller than either Colombia or Peru (together, these are the only three countries that produce and export significant quantities of coca ), particularly when coca used for legal purposes is taken into account.

The White House’s September 14 determination concludes that Bolivia has “failed demonstrably during the previous 12 months to adhere to [its] obligations under international narcotics agreements,” basing this assertion on a dismissal of the gains made via declining coca cultivation and what appear to be exaggerated estimates of potential cocaine production.[xlviii] The lack of transparency about how U.S. officials calculate cocaine production estimates, as described above, combined with the contention that Bolivia is producing more cocaine than Colombia—despite having far less land under coca cultivation than Colombia or Peru—further erodes U.S. credibility in Bolivia. Moreover, it is not lost on the Bolivian government that every year Peru is lavished with praise from Washington, despite significant and steady increases in both coca cultivation and estimated potential cocaine production in that country.

Bolivia and 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs

Another point of contention in bilateral relations is U.S. opposition to Bolivia’s re-admission to the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs as amended by the 1972 Protocol. Bolivia is seeking to reconcile its new constitution with its international commitments. Article 384 of the 2009 Constitution states: “The State shall protect native and ancestral coca as cultural patrimony, a renewable natural resource of Bolivia’s biodiversity, and as a factor of social cohesion; in its natural state it is not a narcotic. Its revaluing, production, commercialization, and industrialization shall be regulated by law.” The Constitution allows for a period of four years for the government to “denounce and, in that case, renegotiate the international treaties that may be contrary to the constitution.”

Hence, in June 2011, the country denounced the 1961 Single Convention and announced its intention to re-accede with a reservation allowing for the traditional use of the coca leaf. Unless more than one-third of UN member states object by the January 10, 2013 deadline, the Bolivian reservation will be accepted and it will once again be a full Party to the Single Convention.

The U.S. government’s July 2012 formal letter of objection states:

The United States considers the Convention to be one of the cornerstones of international efforts to prevent the illicit production, manufacture, traffic in and abuse of drugs, while ensuring that illicit drugs are available for medical and scientific purposes. The United States is concerned that Bolivia’s reservation is likely to lead to a greater supply of available coca, and as a result, more cocaine will be available for the global cocaine market, further fueling narcotics trafficking and related criminal activities in Bolivia and the countries along the cocaine trafficking route.[xlix]

But in seeking the reservation, Bolivia has been following established Convention guidelines. It also took this action after its effort to amend the Single Convention by deleting its provision obligating that “coca leaf chewing must be abolished” within 25 years (Article 49). The U.S. government led opposition to this amendment, even though it is quite clear that the elimination of coca chewing is not feasible and that that the practice is widely accepted in many sectors, in Bolivia and internationally. In contrast, with regard to Bolivia’s intent to re-accede to the Single Convention with a reservation, U.S. officials claim that they are not organizing opposition to Bolivia’s actions and that they do not expect more than one-third of UN member states to object. At the time of this writing, only the U.S. government had presented a formal objection, although others have indicated that they would also do so.

The Bolivian government is optimistic that they will be returning to the Convention in January 2013. Foreign Minister Choquehuanca did a tour of European countries in October 2012 to press the government’s case. According to Vice Minister of Coca Dionicio Nuñez, “The international campaign has gone well. We are optimistic that we will be able to return to the convention.”[l] One sticking point with European governments is the release of an EU-funded study on the traditional uses of coca, which is intended to provide the baseline for how much coca should be produced in Bolivia for legal purposes. It is now years behind schedule, but Bolivian authorities have stated that they are finishing some complementary components of the study and that it will be released in the first half of 2013.[li]

The Bolivian government registered a diplomatic advance at the November 2012 Ibero-American Summit held in Cádiz, Spain. At that summit, a special communiqué was adopted on the traditional use of coca chewing in which the presidents unanimously stated:

Conscious of the importance of conserving the ancestral and cultural practices of indigenous peoples, in the framework of respect for human rights and the fundamental rights of indigenous peoples, in accordance with international instrument … We recognize that the traditional use of coca chewing (akulliku) of the coca leaf is a cultural and ancestral manifestation of the people of Bolivia and Peru and should be respected by the international community.[lii]

In other words, Bolivia now has at least tacit support from all Latin American countries, as well as Spain and Portugal, for eliminating the international stigma presently—and erroneously—associated with the coca leaf.

Conclusions

Critics of Bolivia’s UN coca initiative are forced to balance concerns of the precedent set by allowing a country to re-accede to the 1961 Single Convention with a reservation against the implications of Bolivia’s permanent withdrawal from the international drug control system. Staunch defenders of the conventions fear that permitting Bolivia to re-enter the Single Convention with a reservation upholding traditional uses of the coca leaf could potentially open up a Pandora’s box, with other countries proposing changes that call into question the fundamentals of the current treaties. However, the 51-year old international drug control regime must prove that it can adapt and adjust to the changing dynamics of the drug trade. The inclusion of the coca leaf in the 1961 Convention was a historic error whose correction is long overdue. Moreover, regardless of whether or not Bolivia returns to the Single Convention, coca cultivation will continue in Bolivia, and the UN conventions should be adapted to align with that reality.

The Bolivian government has made clear its intention to continue to engage with the U.S. government, the European Union, and neighboring countries on drug control and has significantly reduced overall levels of coca cultivation and has increased drug seizures, among other drug control actions. In other words, Bolivia clearly wishes to continue playing by the established rules of the game to address illicit drug trafficking.

The Bolivian government has in fact made significant progress facing the ongoing challenges of drug production and trafficking, in part due to the assistance provided by the EU, the United States, and others. The U.S. government should now recognize this progress in its annual determinations. The string of negative determinations is increasingly disconnected from reality in Bolivia and retains little credibility with the Bolivian government or with other governments in the region, which continue to see the annual U.S. rating as offensive and politically motivated. Along the same lines, the potential cocaine statistics presented by the U.S. government in last year’s determination were met with disbelief in Bolivia. Given the ongoing doubts about the reliability of such estimates, the U.S. government should be transparent about exactly how it performs these calculations.

The signing of the framework agreement marked significant progress in U.S.-Bolivian bilateral relations. Both governments should build on that success by using the accord as a venue to discuss areas of concern, friction, and consensus. While differences will undoubtedly arise, it is in the best interests of both countries to maintain an open dialogue.

Bolivia faces daunting challenges from drug production and trafficking. While the government has an innovative national strategy for addressing these challenges, the increasing militarization of its borders and proposed air interdiction raise a variety of concerns. Moreover, the continued growth in regional and global cocaine consumption means that Bolivia cannot and should not be expected to solve the problems associated with cocaine production and trafficking, even within its own borders. Bolivia’s efforts must be carried out in tandem with effective demand reduction strategies to contain and eventually shrink the global cocaine market.

Kathryn Ledebur is the Director of the Andean Information Network (AIN) based in Cochabamba, Bolivia. Coletta A. Youngers is a Senior Fellow at the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA). WOLA Senior Associate John M. Walsh, WOLA Program Assistant Adam Schaffer, and AIN Program Assistant Jessica Robinson also contributed to this report.

This report was made possible with the generous support of the Open Society Foundations.

[i] Morales won the December 2005 elections with 53.7 percent of the popular vote. He was reelected in December 2009.

[ii] The White House. White House Presidential Determination: Memorandum of Justification for Major Illicit Drug Transit or Illicit Drug Producing Countries for Fiscal Year 2013. Washington, D.C.: September 14, 2012.

[iii] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia: Monitoreo de Cultivo de Coca, September 19, 2012. https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/frontpage/2012/September/coca-crop-cultivation-falls-significantly-in-bolivia-according-to-2011-coca-monitoring-survey.html

[iv] One hectare is roughly 2.5 acres.

[v] Authors’ interview. September 28, 2012.

[vi] Coletta A. Youngers and Kathryn Ledebur. WOLA and AIN. “Washington in Wonderland.” http://www.wola.org/commentary/washington_in_wonderland

[vii] “La paradoja es que hay menos cocales pero hay más cocaína,” Página Siete, July 14, 2012.

[viii] A cato is 1,600 square meters, or about a third of an acre, in the Chapare, and 2,500 square meters in the Yungas (where farmers argue the coca plant yield is less than in the Chapare).

[ix] Authors’ interview, September 26, 2012.

[x] In the Chapare region, there are six coca grower unions that together form the Six Federations of the Cochabamba Tropics (Seis Federaciones del Trópico de Cochabamba).

[xi] Authors’ interview, September 24, 2012.

[xii] Authors’ interview, September 26, 2012.

[xiii] See http://www.mingobierno.gob.bo/pdf/vicemindefsocial.pdf for more information.

[xiv] Authors’ interview with Nicolaus Hansmann, Attaché to the Cooperation Section of the European Union in Bolivia, September 28, 2012.

[xv] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia: Monitoreo de Cultivo de Coca, September 19, 2011, 47.

[xvi] For many small farmers, coca is the family’s only source of cash income.

[xvii] USAID reported supporting the cultivation of 39,834 hectares of alternative crops and the creation of 22,386 jobs in Bolivia in fiscal years 2006 through 2010. At the time of this writing, USAID’s results for fiscal year 2011 have not yet been finalized. See U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO). Counterdrug Assistance: U.S. Agencies Have Allotted Billions in Andean Countries, but DOD Should Improve its Reporting of Results, GAO-12-824, June 2012. 17.

[xviii] Authors’ interview, September 24, 2012.

[xix] Authors’ interview, September 24, 2012.

[xx] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia: Monitoreo de Cultivo de Coca. September 19, 2012, 5.

[xxi]Información Institucional. FONADAL. http://www.fonadal.gob.bo/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=44&Itemid=92

[xxii] As noted earlier, in the Yungas the cato is measured at 2,500 square meters, or one-quarter of a hectare, rather than 1,600 square meters in the Chapare, where yields are higher.

[xxiii] Authors’ interview, Dionicio Nuñez, September 27, 2012.

[xxiv] United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia: Monitoreo de Cultivo de Coca, September 19, 2012. 5.

[xxv] “FELCN y FTC inician operativos en Cocapata” Los Tiempos, November 14, 2012. http://www.lostiempos.com/diario/actualidad/nacional/20121115/felcn-y-ftc-inician-operativos-en-cocapata_192426_409446.html

[xxvi] Authors’ interview, September 27, 2012.

[xxvii] Authors’ interview, September 27, 2012 with Col. Quezada,Director of the Special Force to Fight Drug Trafficking, FELCN, Bolivia’s drug control police.

[xxviii] Authors’ interview with Nicolaus Hansmann, September 27, 2012.

[xxix] Authors’ interview with Nicolaus Hansmann, September 28, 2012.

[xxx] Authors’ interview, September 27, 2012.

[xxxi] Carlos Valdez. “Bolivian official says Brazilian drones aid in locating illegal cocaine labs,” Associated Press, June 21, 2012.

[xxxii] “Brasil espera una respuesta boliviana sobre acción militar,” La Razón, April 30 ,2012; “Bolivia refuerza control militar en la frontera donde lincharon a brasileño,” EFE, August 18, 2012; and “Brasil cierra su frontera con Bolivia por supuestos excesos,” El Diario, November 26, 2012.

[xxxiii] “Bolivia, Brasil y Perú proyectan crear un fondo para la lucha antidroga con dineros de la extinción de bienes,” La Razón, November 14, 2012. http://www.la-razon.com/nacional/seguridad_nacional/Bolivia-Brasil-Peru-extincion-antidroga_0_1724827563.html

[xxxiv] The Transnational Institute. “The Drug War in the Skies.” November 17, 2005. http://www.tni.org/article/drug-war-skies

[xxxv] “Empresa aeronáutica diseña vigilancia para frontera brasileña con Paraguay y Bolivia,” La Razón, November 26, 2012. http://www.la-razon.com/mundo/Empresa-aeronautica-vigilancia-Paraguay-Bolivia_0_1731426897.html

[xxxvi] “UN and U.S. Estimates for Cocaine Production Contradict Each Other.” Just the Facts. July 31, 2012. http://justf.org/blog/1?page=1

[xxxvii] “Excess coca leaf is being diverted to the production of cocaine hydrochloride. Compounded by improved processing methods, the United States Government estimates potential cocaine hydrochloride production increased in Bolivia during 2008 by 50 percent to 195 metric tons.” U.S. Department of State. Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs. 2010 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report, March 1, 2010. http://www.state.gov/j/inl/rls/nrcrpt/2010/vol1/137190.htm .

[xxxviii] Special thanks to Jeremy Bigwood for providing documentation on Operation Breakthrough.

[xxxix] “Using a water-pit, leaf-stomping technique, both the Peruvian and Bolivian ‘chemists’ were capable of extracting some 45 percent of the cocaine alkaloid from the leaf … Colombian cocaine base processors use and entirely different production method … it is reasonable that Colombian ‘chemists’ may be capable of extracting as much as 70 percent of the cocaine alkaloid from the leaf.” DCI Crime and Narcotics Center and the Drug Enforcement Administration. Colombia: Coca Cultivation and Preliminary Results from Operation Breakthrough, May 2000, 8. http://www.drugpolicy.org/docUploads/bigwood_coca_op_breakthrough.pdf .

[xl] U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration Intelligence Report. Operation Breakthrough: Coca Cultivation & Cocaine Base Production in Bolivia, July 1994, DEA-94032, 1.

[xli] Ibid. 16.

[xlii] International Narcotics Control Strategy Report: Bolivia, March 7, 2012.

[xliii] Authors’ interview with César Guedes. September 28, 2012.

[xliv] Testimony of Ambassador William R. Brownfield, Assistant Secretary of State, Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs before the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations Subcommittee on the Western Hemisphere, Peace Corps, and Global Narcotics Affairs Hearing on “A Shared Responsibility: Counternarcotics and Citizen Security in the Americas,” March 31, 2011.

[xlv] “La paradoja es que hay menos cocales pero hay más cocaína,” Página Siete, July 14, 2012.

[xlvi] Williams Farfán. “Obama destaca el pacto antidrogas con Bolivia y Brasil,” La Razón, April 14, 2012. http://www.la-razon.com/nacional/seguridad_nacional/Obama-destaca-antidrogas-Bolivia-Brasil_0_1595840433.html

[xlvii] Authors’ interview, September 28, 2012.

[xlix] The Secretary-General of the United Nations. United States Of America: Objection To The Reservation Contained In The Communication By The Plurinational State Of Bolivia, July 3, 2012. Reference: C.N.361.2012.TREATIES-VI.18.

[l] Authors’ interview, September 27, 2012.

[li] “Difundirán en mayo estudio de la coca, base de futura ley antidrogas,” Los Tiempos, November 26, 2012. http://www.lostiempos.com/diario/actualidad/nacional/20121126/difundiran-en-mayo-estudio-de-la-coca-base-de-futura-ley_193581_412158.html

[lii] Authors’ translation from original Spanish.