On March 9th, 2013, the Bolivian government passed a new comprehensive and progressive law to combat violence against women. The law includes preventative measures, wide-ranging services to survivors of abuse, and severe penalties for violence against women. The law represents a great advance from previous legislation, which did not consider spousal rape a crime and dictated sentences of only 4-10 years. The impetus for the new law was in large part from several high-profile, brutal attacks over the past few months. While the law is a victory for women’s rights advocates, it real impact remains to be seen. Sources of funding for the ambitious new programs and services have yet to be defined, and compliance and enforcement of the new law will be an uphill battle.

Recent High-Profile Cases

On Monday, February 11th, a police lieutenant stabbed his ex-wife, journalist Hanalí Huaycho, 15 times. On the same night as Huaycho’s attack, a woman from Santa Cruz was stabbed 17 times by her husband. Just two days later, another female journalist was brutally assaulted by her boyfriend, also a police officer.

These attacks come in the wake of a December 2012 scandal that captured two members of the Chuquisaca Departmental Assembly on a security camera raping an employee who had passed out during an office Christmas party. The footage was widely broadcast by Bolivian television stations.

These incidents reveal the deep flaws in the legal system and its failure to protect Bolivian women against violence. Huaycho had denounced her ex-husband, Jorge Clavijo, 14 times since 2008. Huaycho reported that Clavijo beat her, cut the breaks of her car, and locked Huaycho and their six-month old son inside a vehicle and threw tear gas inside. However, her attempts to obtain protection from Clavijo only resulted in death threats to her and her lawyer. Minister of the Government Carlos Romero affirmed that Clavijo enjoyed police protection.

There was immediate public outrage over Huaycho’s death, including a demonstration in La Paz. Police tear-gassed protesters, among which were the wife of the vice-president, the president of the Chamber of Senators, the president of the Chamber of Deputies, the president of the Permanent Human Rights Assembly, and the Autonomy, Justice and Communications Ministers.

The attacks provided impetus for the government to pass a new, comprehensive law with preventative measures as well as harsh sanctions against offenders. It is important to note, however, that in Bolivia and around the world, countless cases of violence against women are invisible to the media.

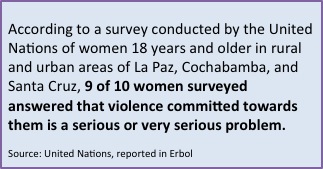

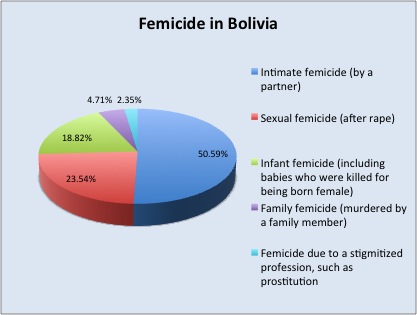

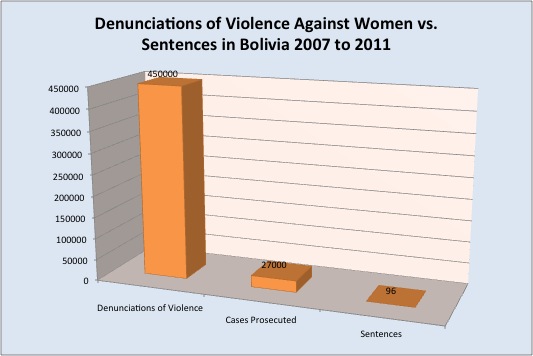

Scope of Violence Against Women in Bolivia

Source: Los Tiempos

Source: Los Tiempos

The Comprehensive Law to Guarantee Women a Life Free of Violence

President Morales passed the “Comprehensive Law to Guarantee Women a Life Free of Violence,” on March 9th, 2013. The law is extremely ambitious and comprehensive, with provisions for educational and awareness programs, practical measures to prevent reoccurring violence, plans to rehabilitate offenders, detailed descriptions of 15 different types of violence against women, and strict sanctions against offenders.

Highlights of the new law include:

- Increased and harsher sentences for violence against women

- Sentences increased from 4-10 years to 20-30 years.

- Spousal rape is now a crime, and adds five years to the standard rape sentence.

- Comprehensive sanctions against a wide range of types of violence against women

- The law defines 15 categories of violence against women, including violence in the media; violence against the honor, dignity, and name of women; patrimonial and economic violence; and institutional violence, which includes purposely delaying or denying access to services.

- Culturally sensitive and inclusive language, including:

- A guarantee of equal opportunities regardless of ethnic origin or sexual orientation

- An intercultural perspective

- Priority of service to rural areas, where incidents of violence are greater

- Training programs about violence against women in all public institutions and health institutions

- Media campaigns to inform and sensitize the population about the causes, types, and consequences of violence against women

- The media must provide a minimum, free broadcast space to the government.

- A sanction against holding public office for those with convictions related to violence against women

- New requirements for people in public posts or services related to women to have training and experience in either themes of gender, women’s rights, or human rights

- Participation of social organizations and civil society organizations dedicated to women’s rights in the design, evaluation, and management of public policies against violence

- Compliance and the adoption of prevention strategies for indigenous, Afro-Bolivian communities, and autonomous territories

- Curriculum about peaceful conflict resolution, human rights, and violence against women in the education system, including at the university level

- Sanctions for people in positions of authority who fail to report violence

- Access to job placement systems and training for women in shelters

- Rehabilitation of offenders, including therapy and conflict resolution training

- Comprehensive protocols for protecting women after an act of violence, including procedures to recover her possessions and secure safe housing

- Sanctions against “media violence,” including sexist language

- Sanctions against economic violence

- It is now a crime to hinder a women’s ability to generate income.

- Free medical certificates for women who require treatment for violence

Enforcements, Funding, and Lack of Clarity Complicate Law’s Implementation

While the new law is ambitious and progressive, there are several causes for concern. It includes problematic gray areas, which could provoke conflict. For example, the law states that it will regulate the media, but does not specify how, which could lead to protests of censorship. It also requires the media to adopt a self-regulated ethics code regarding portrayals of women, but does not specify its content or mechanisms for enforcement. In addition, the new law stipulates that workplaces must have a “system of flexibility and tolerance” for women in situations of violence, but fails to provide the means to evaluate these measures.

Furthermore, the question still remains of how the government will fund all the mandatory educational programs, sensitivity training, prevention mechanisms, rehabilitation programs, mass media campaigns, and increased law enforcement. The language regarding funding is extremely vague; the law states that necessary adjustments must be made in 2013 budgets, but does not say where institutions should obtain this money. Silvia Vega, a representative of the Integrated Feminine Education Institute (IFFI) explained that although there may be laws protecting women on paper, there is no budget to implement them, and because of this, the existing three laws and five decrees that legislate against violence against women have not been enforced.

Source: Los Tiempos

Source: Los Tiempos

In addition, although the law specifically states that indigenous communities, Afro-Bolivian communities, and those living in autonomous territories are also subject to this law, in most cases, these communities lack the resources and infrastructure to properly implement it.

In conclusion, while the law represents a significant advance in the fight against violence against women, its successful implementation faces tremendous challenges.