This article was originally published in Stability: International Journal of Security and Development. View full text and .pdf versions here.

From Conflict to Collaboration: An Innovative Approach to Reducing Coca Cultivation in Bolivia

Kathryn Ledebur* and Coletta A. Youngers1†

*Director of the Andean Information Network (AIN), Cochabamba

†Senior Fellow at the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA), United States

Upon his presidential election, Bolivian coca grower leader Evo Morales adopted a policy of promoting consensual coca reduction through social control, a sophisticated coca monitoring system, and economic development. That strategy is paying off. In 2011, coca cultivation decreased by 13 per cent according to the U.S. government. The Morales administration has also made significant progress facing the ongoing challenges of drug production and trafficking. Seizures of coca paste and cocaine and destruction of drug laboratories have steadily increased since President Morales took office. Despite continued tensions in bilateral relations, U.S.-Bolivian counter-drug cooperation continues and the signing of a new framework agreement in 2011 should lead to an exchange of ambassadors. Internationally, Bolivia has successfully gained acceptance of the right to the traditional use of coca within its own territory. But Bolivia’s efforts must be carried out in tandem with effective demand reduction strategies to shrink the global cocaine market.

Introduction

For decades, Bolivia faithfully carried out forced eradication of the coca leaf2 – the raw material used for processing cocaine – as required by the U.S. government to receive economic assistance and trade benefits. However, Bolivians paid a high price for waging Washington’s ‘war on drugs’. Forced coca eradication efforts generated social unrest, violence, and political instability. Human rights violations proliferated, including arbitrary detentions, mistreatment of the local population and, in some cases, torture and killings. Targeting poor farmers, the eradication strategy plunged families deeper into poverty.

However, the election of coca grower leader Evo Morales in January 2006 radically transformed that scenario.3 The Morales government adopted a strategy best summarized as ‘coca yes, cocaine no’, which is aimed at decreasing the cultivation of coca while increasing law enforcement efforts targeting cocaine production and drug trafficking organizations. The government’s policy of promoting gradual and consensual coca reduction through economic development and improved livelihoods is paying off. In 2011, the land area devoted to coca cultivation in Bolivia dropped by 13 per cent, according to U.S. government figures, in contrast to net increases in Peru and Colombia. And the violence and conflict that characterized past policy is largely a thing of the past. Seizures of coca paste and cocaine as well as the destruction of drug laboratories have steadily increased since President Morales took office. Yet despite the positive results achieved to date, the government faces increasing challenges as the amount of coca paste (pasta base) and cocaine flowing across its borders from Peru has increased, the production of cocaine in Bolivia itself has risen, and drug traffickers have diversified and expanded areas of production and transportation within the country.

As a long-standing foe of U.S. drug policy, many expected Morales to break ties with Washington and put a stop to drug policy cooperation. Instead, both Morales and the George W. Bush administration initially kept the rhetoric at bay and developed a workable bilateral relationship – though one that at times has been fraught with tension. Following Bolivia’s expulsion in 2008 of the U.S. Ambassador, Philip Goldberg, for allegedly meddling in the country’s internal affairs and encouraging civil unrest, and the subsequent expulsion of the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), the White House upped its criticism of the Bolivian government and for the past five years has issued a ‘determination’ that Bolivia has ‘failed demonstrably during the previous 12 months to adhere to [its] obligations under international narcotics agreements’ (The White House 2012). U.S. economic assistance for Bolivian drug control programs has slowed to a trickle. Nonetheless, in 2011 the two countries signed a new framework agreement to guide bilateral relations and are planning an exchange of ambassadors.

At the international level, Bolivia is seeking to reconcile its new constitution, which recognizes the right to use the coca leaf for traditional and legal purposes and that coca is part of the country’s national heritage, with its commitments to international conventions. In June 2011, the country denounced the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs as amended by the 1972 Protocol and announced its intention to re-accede with a reservation allowing for the traditional use of the coca leaf (List 1 of the 1961 Convention mistakenly classifies coca as a dangerous narcotic). A minimum of one-third of the 184 members of the treaty would have had to object to prevent Bolivia from rejoining the convention, yet only 15 countries did so. Bolivia has scored a historic victory for its people. However, coca remains illegal outside of the country and the historic error in the classification of the coca leaf has yet to be corrected.4

Cooperative Coca Reduction Strategy Produces Results

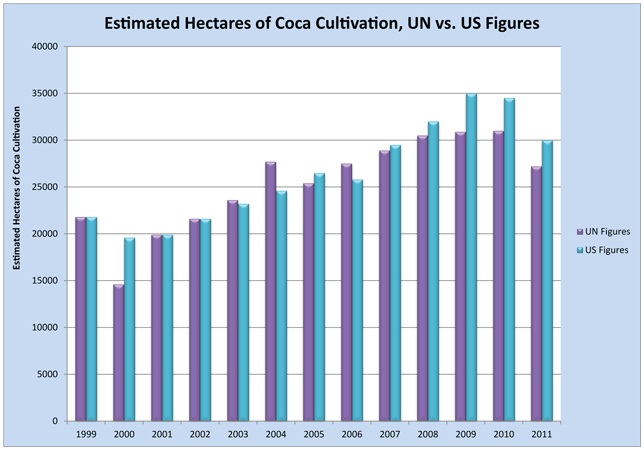

In September 2012, both the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and the U.S. government released their 2011 statistics on coca cultivation in Bolivia (Figure 1). The convergence of the coca cultivation estimates, which differed by only one per cent, highlight the effectiveness of the government’s coca crop monitoring strategy. The statistics also point to the effectiveness of the cooperative coca reduction strategy. In contrast, according to the UNODC, in 2011 Colombia cultivated 64,000 hectares of coca and Peru 62,500 hectares, representing three and five per cent increases, respectively.

Figure 1: Estimated Hectares of Coca Cultivation, UN vs U.S. Figures. Source: UN Crop Monitoring Reports and U.S. International Narcotics Control Strategy Reports

Figure 1: Estimated Hectares of Coca Cultivation, UN vs U.S. Figures. Source: UN Crop Monitoring Reports and U.S. International Narcotics Control Strategy Reports

According to the UNODC’s 2011 Coca Cultivation Survey, coca cultivation in Bolivia fell to 27,200 hectares5 in 2011 from 31,000 hectares in 2010 – a 12 per cent decrease (UNOCD 2012). The report notes that coca cultivation declined in every important coca-growing region in the country, bringing the overall area under cultivation to near the 2005 level. The UN attributes this ‘significant’ decrease to ‘effective control’ through cooperative coca reduction and eradication. The UN also reports a 13 per cent reduction in overall coca leaf yields, down to 48,100 metric tons in 2011 from 55,500 metric tons in 2010. According to the head of the UNODC office in Bolivia, César Guedes, ‘The progress in Bolivia is undeniable. This year, Bolivia is the only country with a decrease in coca cultivation…The facts are sufficiently clear, not only with regards to coca cultivation but also with a long list of verifiable successes.’ Similarly, the White House’s 14 September 2012 determination reports that the 2011 U.S. government coca cultivation estimate for Bolivia was 30,000 hectares, a 13 per cent decrease in Bolivia’s coca crop (Guedes 2012; Youngers and Ledebur 2012).

The Morales administration’s coca reduction strategy is based on the voluntary participation of farmers from all coca-growing regions in the country. Each farmer in the Chapare coca-growing region6 is allowed to grow one cato of coca,7 continuing a policy adopted by the Carlos Mesa government in 2004. Any coca grown beyond that limit, or in regions not covered by the cato agreement, is subject to elimination. The strategy’s relative success hinges on the ability of the powerful coca growers federations’ ability to enforce the agreement.8 The sanctions imposed by the federations for failure to comply with the one cato limit are severe, including the loss of the right to grow coca and, ultimately, land expropriation for repeat offenders. As a result of the cato agreement, the violence and conflict generated by forced eradication in the Chapare has, with rare exceptions, ceased.

The Bolivian government has expanded the cooperative coca reduction approach into areas of the country, such as parts of the La Paz Yungas, where no significant coca eradication had previously occurred. For many years, coca production in the Chapare region far exceeded that in La Paz Yungas, but the success of cooperative coca reduction in the Chapare has meant that the Yungas is now the country’s largest coca producing region, with 67 per cent of the national crop (UNODC 2012: 5). Prior governments were unable to reduce excess coca planting in this region, but the Morales administration has initiated reductions through extensive negotiation and integrated development efforts which seek to complement income provided by coca. Beginning in 2006, the government has implemented hundreds of infrastructure, economic development, institutional strengthening, and social development projects, primarily in coca-producing zones, with an emphasis on consultation with the participating families and food security (FONDAL 2011). Launching these participatory development initiatives before negotiating coca reduction has helped the Morales administration begin to implement the cato system in the Yungas and establish coca production ceilings for other areas of the Yungas. The UNOCD reported an 11 per cent reduction in coca cultivation in the Yungas in 2011.

According to the UNODC, in 2011 coca cultivation declined in all coca-growing regions, including national parks (resulting in the nationwide 12 per cent decrease noted earlier). As noted, in the Yungas, there was an 11 per cent decrease, in Apolo-Norte de La Paz seven per cent, and in the Chapare 15 per cent. National parks also saw a 15 per cent reduction, resulting from forced eradication. The UNODC data show that cooperative coca reduction through social control is the driving force behind declining coca cultivation. Still, the government faces the challenge of the continuing spread of coca into new areas, including national parks.

Promoting Equitable Economic Development

For the farmer, limited coca production maintains a relatively stable and high price for coca and a guaranteed subsistence base. According to the UNODC 2011 report, the price for coca in the legal and illegal markets is the same, providing little comparative incentive to deviate from legal sales. The secure income generated from the cato of coca also allows for experimentation with other income-generating activities so that farmers can diversify their sources of income, reducing their dependence on income generated from coca. Concrete data is hard to come by, but farmers appear to be taking advantage of a range of income-generating opportunities. The UNODC points to significant agricultural diversification in the core area of the Chapare region (excluding national parks). According to its 2011 coca monitoring survey, bananas covered the largest area cultivated in the Chapare, followed by citrus fruit and palm hearts and then coca. UNODC attributed this phenomenon to sustained, integrated development efforts (UNODC 2012: 47).

At the same time, the Morales government is implementing programs to improve the overall quality of life of the local population. In spite of a lack of available statistics, many actors agree that the overall quality of life in the Chapare has improved due to increased government investment in education, health, and transportation. A generation of children of Chapare coca growers has now graduated from local universities, returning to the area with a range of technical skills. Banana exports to Argentina have become a mainstay of the local economy and, in addition to the crops listed above, farmers are investing more in products such as honey, coffee, and chocolate, and some are investing in cattle. Others are getting involved in small-scale businesses, such as marketing or transportation services.

An Innovative and Comprehensive Approach to Coca Monitoring

Through its coca monitoring strategy, the government can ensure that the cato agreement is respected. It is a unique model incorporating the active, voluntary participation and engagement of coca farmers with state institutions, as well as information sharing and engagement with international entities and agencies, including the United Nations, the European Union, the United States, and Brazil. The General Coca Production Directorate (Dirección General De Desarrollo Integral De Las Regiones Productoras De Coca, DIGPROCOCA) registers the catos and provides farmers with land titles. That registry is part of a sophisticated database, SYSCOCA, which cross-references the information with satellite images, aerial photography, en situ inspections, and measurements with GPS and laser distance meters and recently updated land tenure information. This information is then used to plan cooperative coca reduction. SYSCOCA is part of the EU-funded Coca Social Control Support Program, and the database is also shared with the UNODC’s Coca Monitoring Project. Most coca plots are monitored several times a year by satellite, ground verification by three different offices, and aerial photography.

As a part of the monitoring effort, the EU has funded a biometric registry of coca producers, each of whom is to receive his or her own personal identification card. The registry of over 48,0009 producers has been completed and the ID cards, which contain an electronic chip to facilitate government control, will be distributed to each authorized farmer. The SYSCOCA database described above provides Bolivian government officials with up-to-date information on the precise amount of coca planted, to whom it belongs, and whether it complies with national law. Through the electronic ID and the information obtained in the registry, government officials will be able to trace the harvest of the coca leaf and its sale in the legal local market. This will also allow the government to be able to trace coca diverted from the legal market with greater efficiency (Hansmann 2012).

Of particular significance, the Bolivian government plans to extend the biometric registry, with EU support, to control the transit, sale, and marketing of the coca leaf. Eventually, anyone involved in the legal transportation or sale of coca will have an identification card and will thereby be entered into the system. Then, by scanning their respective biometric identification card, the government will be able to monitor the transportation of coca by registered intermediaries to the two authorized wholesale markets and its distribution to individual vendors. When fully implemented, the system, which requires the technological equivalent of a smart phone, will represent a dramatic improvement over the current paper records, allowing for more complete and rapid information sharing. Though no system is foolproof, and multiple obstacles still stand in the way of the effective implementation of the monitoring program, it nonetheless represents a pragmatic and ambitious effort to control the diversion of coca to illicit markets.

Disrupting Drug Trafficking

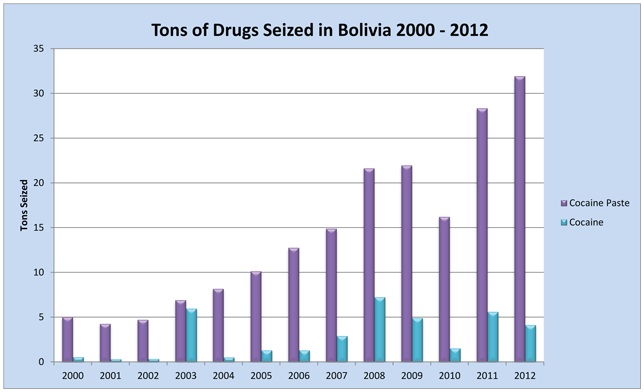

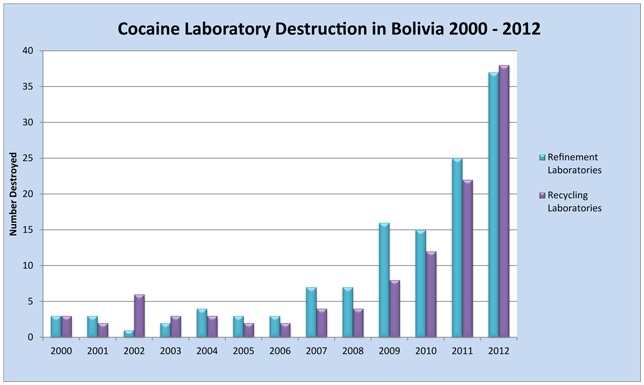

Even though coca production declined significantly in 2011, the Bolivian government confronts a growing drug trade in the country. The institutional challenges are formidable as Bolivia faces severe budget limitations and limited technical capacity in dealing with a complex criminal enterprise with virtually unlimited funds. Nonetheless, since the Morales administration took office in 2006, increased enforcement efforts have led to a steady increase in seizures of coca pasta and cocaine, as well as destruction of ‘laboratories’, mostly small-scale production sites (see Figures 2 and 3). According to the EU’s Nicolaus Hansmann, going after the drug trade is ‘one of the top priorities of the government as they know that both internally and externally the worst damage that they can do to [the Movement for Socialism party, MAS] is to associate it with drug trafficking’ (Hansmann 2012).

Figure 2: Tons of Drugs Seized in Bolivia, 2000–2012. Source: Vice-Ministry of Social Defense and Controlled Substances of Bolivia and Special Force against Drug Trafficking (FELCN)

Figure 2: Tons of Drugs Seized in Bolivia, 2000–2012. Source: Vice-Ministry of Social Defense and Controlled Substances of Bolivia and Special Force against Drug Trafficking (FELCN)

Figure 3: Cocaine Laboratory Destruction in Bolivia, 2000–2012. Source: Vice-Ministry of Social Defense and Controlled Substances of Bolivia and FELCN

Figure 3: Cocaine Laboratory Destruction in Bolivia, 2000–2012. Source: Vice-Ministry of Social Defense and Controlled Substances of Bolivia and FELCN

Bolivian authorities have repeatedly expressed concern about the presence of international drug trafficking organizations in the country, something they largely attribute to Bolivia’s geography. The country is in the center of the continent, is the most efficient corridor through Argentina and on to West Africa (now a major transshipment point for illicit drugs en route to Europe and other parts of the world), and borders the second largest cocaine market in the world, Brazil. In addition, Bolivia offers comparatively low operating costs due to fuel subsidies and provides a safer operating environment as it does not suffer from the violence associated with drug trafficking in Mexico and Colombia.

Traditionally, elite, geographically-concentrated families dominated drug trafficking in Bolivia. In recent years, however, trafficking networks have diversified, tend to concentrate on one part of the drug trafficking chain, and have spread throughout the country. The great bulk of drug production and trafficking in Bolivia is now carried out by small family ‘clans’, none of which has a significant share of the market. The arrest and disbanding of one group hardly makes a dent in the drug trade as it is quickly and easily replaced.

Another major challenge for Bolivian authorities is that approximately half of the coca paste and cocaine seized in the country originates in Peru. As the price of a kilo of coca paste is US$200 higher in Bolivia than Peru, more and more coca paste is being brought from Peru into the country, where it is either processed into cocaine or transported directly to Brazil where it is converted to paco, a highly addictive cocaine derivative.

The U.S. government claims that the expulsion of the DEA, which left Bolivia in January 2009, permanently impeded Bolivia’s ability to deal with drug trafficking and calls into question President Morales’ political will to implement effective drug control policies. With the DEA’s departure, however, Bolivia has begun to work closely with its neighbors on a range of drug control initiatives and has signed bilateral agreements with Brazil, Peru, Argentina, Paraguay, Colombia, and others. Moreover, according to an analysis carried out by Bolivian authorities, since the DEA left Bolivia cocaine interdiction has increased by 234 per cent, the number of illicit drug laboratories destroyed has increased three-fold, and drug control operations have increased significantly (Incautación de cocaine 2013).

U.S. Policy toward Bolivia

Despite the expulsion of the DEA, the Bolivian Ministry of Government’s Vice Ministry of Social Defense and Controlled Substances and the U.S. Embassy’s Narcotics Affairs Section (NAS) maintain daily cooperation on the ground. The NAS continues to fund drug and coca control efforts – albeit with a significantly reduced budget – and coordinates with the Bolivian government on a daily basis. In November 2011, bilateral relations were formally restored through the signing of a framework agreement that includes regular drug policy meetings and the governments announced their intention to reinstate ambassadors. In January 2012, Bolivia, Brazil, and the United States signed a trilateral coca cultivation monitoring agreement.

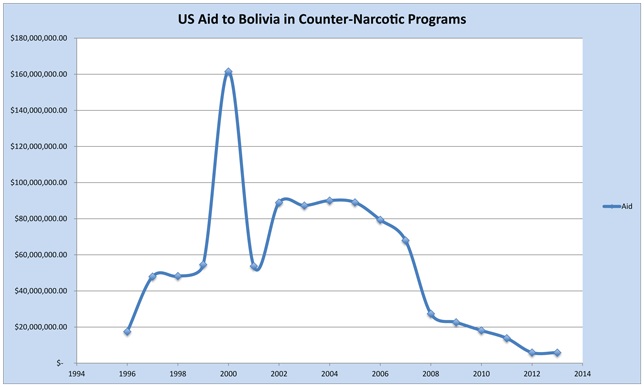

As demonstrated in Figure 4, U.S. economic assistance to Bolivia has declined steadily since President Morales came into office. This is largely due to overall budget cuts, vocal opposition on the part of key Republican members of Congress to Morales’ relationship with former Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez and Cuba’s Raúl Castro, and in protest of the expulsion of the DEA. However, the Bolivian government prefers less aid to greater funding with strings attached. As noted by Foreign Minister Choquehuanca, ‘We would rather have good relations without economic assistance than economic assistance whose use is dictated by the United States’ (Choquehuanca 2012).

Figure 4: U.S. Drug Control Funding to Bolivia (US$). Source: U.S. International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) reports via Just the Facts

Figure 4: U.S. Drug Control Funding to Bolivia (US$). Source: U.S. International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) reports via Just the Facts

However, two issues in particular have put significant strain on the bilateral relationship: the annual U.S. ‘determination’ and U.S. opposition to Bolivia’s re-admission to the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. The continuation of the unilateral annual U.S. drug control ‘determination’ (previously called ‘certification’) – in which the United States judges which countries are effectively meeting international drug control obligations – is widely criticized across Latin America. The Obama administration has continued the practice of its predecessor of giving Bolivia a failing grade (along with Venezuela and Myanmar). However, in the case of Bolivia, the numerous errors and inaccuracies – particularly evident in the 2012 determination – give the impression that the decision is based on political motivations rather than an accurate assessment of drug control efforts on the ground.

The White House’s 14 September 2012 determination concludes that Bolivia has ‘failed demonstrably during the previous 12 months to adhere to [its] obligations under international narcotics agreements’, basing this assertion primarily on what appear to be exaggerated estimates of potential cocaine production (The White House 2012). Despite reporting declining coca cultivation in 2010 and 2011, the U.S. government announced a staggering increase in Bolivia’s potential cocaine production: from an estimated 195 metric tons, which held steady from 2008 to 2010, to a potential production of 265 metric tons in 2011. In other words, even with the U.S.-estimated 13 per cent reduction in coca, Washington asserted that Bolivia’s potential cocaine production increased by 36 per cent and that the country is now producing more cocaine than Colombia, which has more than twice the amount of coca under cultivation. The Bolivian government itself estimates that approximately 80 metric tons could be produced in the country. The UNODC’s 2011 coca cultivation report on Bolivia did not provide any data on potential cocaine production, although they reported a 13 per cent decrease in coca yields, which would suggest a reduction, rather than an increase, in potential cocaine production.

U.S. officials maintain that the increase in potential cocaine production in Bolivia is due to more efficient processing methods (ironically, the same methods used in Colombia) and to the maturity of existing fields, which contribute to higher yields. All agree that more cocaine can be produced with less coca in Bolivia today. Yet that would be unlikely to account for such a dramatic increase in potential production. Furthermore, the U.S. government announced a 50 per cent increase in its estimates of Bolivia’s potential cocaine production in 2008, using the same argument – more efficient cocaine processing methods.10 In short, U.S. officials claim that potential cocaine production more than doubled in three years, despite reductions in coca cultivation, each time pointing to the adoption of Colombian processing methods.

Most disturbingly, the U.S. government provides no information whatsoever about how they derive these statistics, giving credence to allegations that the numbers are constructed for political purposes.11 It is not lost on the Bolivian government that every year Peru is lavished with praise from Washington, despite significant and steady increases in both coca cultivation and cocaine production in that country.

Bolivia and the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs

Since President Nixon first launched the U.S. ‘war on drugs’, U.S. drug policy officials have maintained that eradicating the coca plant – perceived as the weakest link in the drug trafficking chain – will lead to reduced cocaine production. Decades later, coca cultivation in the Andean region has remained relatively constant (though it has shifted between countries) while cocaine production has increased, in part due to improved processing methods. Yet despite clear evidence that forced eradication has failed to achieve the desired results – while causing a great deal of collateral damage for the poor farmers whose crops are destroyed – the U.S. government has remain wedded to forced coca eradication.

The U.S. government has also remained opposed to any modifications of the international drug control treaties which it had a major role in crafting. Hence, another point of contention in bilateral relations is U.S. opposition to Bolivia’s re-admission to the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs as amended by the 1972 Protocol. In taking that action, Bolivia was reconciling its new constitution with its international commitments. Article 384 of the 2009 Constitution states, ‘The State shall protect native and ancestral coca as cultural patrimony, a renewable natural resource of Bolivia’s biodiversity, and as a factor of social cohesion; in its natural state it is not a narcotic. Its revaluing, production, sale, and industrialization shall be regulated by law.’ The Constitution allows for a period of four years for the government to ‘denounce and, in that case, renegotiate the international treaties that may be contrary to the constitution.’

Bolivia failed to amend the Single Convention by deleting its provision obligating that ‘coca leaf chewing must be abolished’ within 25 years (Article 49). The U.S. government led opposition to Bolivia’s proposed amendment, even though it is quite clear that the elimination of coca chewing is not feasible and that that the practice is widely accepted in many sectors, in Bolivia and internationally.

Hence, in June 2011, the country denounced the 1961 Convention and announced its intention to re-accede with a reservation permitting the traditional use of the coca leaf within its borders. More than one-third of the 184 members of the treaty had to object by 10 January 2013 to block the Bolivian reservation. The U.S. was the first country to object formally. Fourteen other countries followed its lead, well below the number needed to block the Bolivian initiative. As a result, on February 10, Bolivia again became a full Party to the Single Convention. The formal recognition of the reservation is a significant political victory for Bolivia and for efforts to recognize the need to right the historic wrong in the classification of the coca leaf in the 1961 convention.

Recommendations

Staunch defenders of the Single Convention fear that Bolivia’s return with a reservation upholding traditional uses of the coca leaf could open up a Pandora’s Box, with other countries proposing changes that call into question the fundamentals of the current treaties. However, the 51-year old international drug control regime must prove that it can adapt and adjust to the changing dynamics of the drug trade. Fundamental reform of the international drug control conventions is needed to adapt to the realities of today’s drug markets. A first step forward is for the international community to remove the coca leaf from List 1 of the 1961 convention.

With regards to U.S.-Bolivian bilateral relations, the signing of the framework agreement marked significant progress. Both governments should build on that success by using the accord as a venue to discuss areas of concern, friction, and consensus. While differences will undoubtedly arise, it is in the best interests of both countries to maintain an open dialogue.

The Bolivian government has in fact made significant progress facing the ongoing challenges of drug production and trafficking, in part due to the significant assistance provided by the EU and, to a lesser degree, the U.S and others. The U.S. government should now recognize this progress in its annual determinations. The string of negative determinations is increasingly disconnected from reality in Bolivia and retains little credibility with the Bolivian government or with other governments in the region, which continue to see the annual U.S. rating as offensive and politically motivated. Along the same lines, the potential cocaine statistics presented by the U.S. government in the 2012 determination were met with disbelief in Bolivia. Given the ongoing doubts about the reliability of such estimates, the U.S. government should – at the least – be transparent about how it derives these numbers.

Bolivia has developed and implemented a cooperative coca reduction strategy that has largely eliminated the conflict. Yet the country faces daunting challenges from drug production and trafficking. Bolivia cannot and should not be expected to solve the problems associated with cocaine production and trafficking, even within its own borders, on its own. Bolivia’s efforts must be carried out in tandem with effective demand reduction strategies to contain and eventually shrink the global cocaine market.

———————————————

Notes

1 The authors would like to thank AIN Program Assistant Jessica Robinson for her assistance.

2 The coca leaf grows in Bolivia, Peru, and Colombia and has been used for centuries. In its natural form, coca is a mild stimulant that alleviates altitude sickness, stomach pains, and hunger. In fact, for decades the U.S. Embassy in La Paz served coca tea to visitors. Many Andeans chew the coca leaf or brew it in tea. The stimulus from the coca leaf is comparable to a cup or two of strong coffee. The leaf is also an essential element of many Andean religious ceremonies.

3 Morales won the December 2005 elections with 53.7 per cent of the popular vote. He was re-elected in December 2009.

4 For additional analysis and information on the issues in this article see, Kathryn Ledebur and Coletta A. Youngers, Bolivian Drug Control Efforts: Genuine Progress, Daunting Challenges, http://www.wola.org/publications/bolivian_drug_control_efforts

5 One hectare is roughly 2.5 acres.

6 Bolivian law considers two regions as ’traditional coca-growing zones’: part of the La Paz Yungas and one small region in the Cochabamba department. From 1988–2004, the government permitted 12,000 hectares for traditional use. After October 2004 the policy changed allowing approximately 7,000 hectares in the Chapare region, distributed into catos, which had previously been subject to complete forced eradication. The Morales administration further extended this cato policy to parts of the La Paz Yungas, outside the traditional zone where coca production had also been considered as ‘illegal’, such as La Asunta. Coca production is forbidden and subject to forced eradication in national parks.

7 A cato is 1,600 square meters, or about a third of an acre, in the Chapare, and 2,500 square meters in the Yungas (where farmers argue the coca plant yield is less than in the Chapare).

8 In the Chapare region, there are six coca grower unions that together form the Six Federations of the Cochabamba Tropics (Seis Federaciones del Trópico de Cochabamba).

9 See http://www.mingobierno.gob.bo/pdf/vicemindefsocial.pdf for more information.

10 ‘Excess coca leaf is being diverted to the production of cocaine hydrochloride. Compounded by improved processing methods, the U.S. Government estimates potential cocaine hydrochloride production increased in Bolivia during 2008 by 50 per cent to 195 metric tons.’ U.S. Department of State. Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs. 2010 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report, 1 March 2010. http://www.state.gov/j/inl/rls/nrcrpt/2010/vol1/137190.htm

11 For additional information see: Coletta A. Youngers and Kathryn Ledebur. “Washington in Wonderland.” http://www.wola.org/commentary/washington_in_wonderland

References

Guedes, C (Head of the United Nations Office of Drug Crimes) interviewed by Coletta A. Youngers and Kathryn Ledebur 28 September 2012.

Choquehuanca, D (Bolivian Foreign Minister), interviewed by Coletta A. Youngers and Kathryn Ledebur 28 September 2012.

FONDAL 2011 Información Institucional. La Paz: Fondo Nacional de Desarrollo Alternativo. Available at http://www.fonadal.gob.bo/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=44&Itemid=188 [Last accessed 20 November 2012].

Hansmann, N (Attaché to the Cooperation Section of the European Union in Bolivia), interviewed by Coletta A. Youngers and Kathryn Ledebur 27 September 2012.

La Razón 2013 Incautación de cocaine creció en 234% sin participación de la DEA, 20 January.

The White House 2012 White House Presidential Determination: Memorandum of Justification for Major Illicit Drug Transit or Illicit Drug Producing Countries for Fiscal Year 2013, 14 September. Available at http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2012/09/14/presidential-memorandum-presidential-determination-annual-presidential-d [Last accessed 4 February 2013]

UNODC 2012 Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia: Monitoreo de Cultivo de Coca. La Paz: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 19 September. Available at https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/frontpage/2012/September/coca-crop-cultivation-falls-significantly-in-bolivia-according-to-2011-coca-monitoring-survey.html [Last accessed 4 February 2013]

Youngers, CA and Ledebur, K 2012 Washington in Wonderland, 21 September. Available at http://www.wola.org/commentary/washington_in_wonderland [Last accessed 4 February 2013]