Prison reform: Marginal Progress and Unwieldly Challenges

Prison reform: Marginal Progress and Unwieldly Challenges

by Linda Farthing for the Andean Information Network*

Chronic overcrowding, largely created by an overuse of preventive detention, is endemic in Bolivia’s prison system. Most Bolivians support locking up those accused of crimes until their trials take place, believing that it serves to reduce delinquency .[1] The U.S. imposed Drug Law 1008 further exacerbates the congested conditions.

Institutional weakness of the police and judiciary further violate the rights of incarcerated populations, especially the most vulnerable: indigenous peoples, women and juveniles. Efforts by the current government (MAS – Movimiento al Socialismo) at reform have led to declines in pre-trial detention, female incarceration, and drug-related sentences. Nonetheless, police and judicial corruption, insufficient funding, and continuing public opposition to alternatives to incarceration continue to impede any improvement.

Public opinion impedes reform

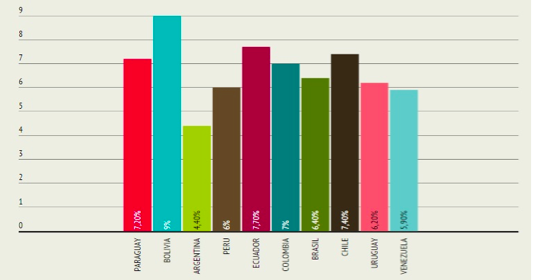

Bolivia has one of the overall lowest crime rates in Latin America, except for violent offenses against women.[2] Yet, its citizens have one of the region’s greatest perceptions of insecurity, fed by sensationalist media reports and mistrust of the police. A Gallup poll reports that 56% of Bolivians do not feel safe walking home alone.[3]

Sixty-five percent of interviewees in a 2014 survey favored punishment over prevention as a means to deter crime.[4] Bolivians generally see prison as the best way to solve citizen insecurity, with little confidence in policies that prevent crime or encourage prisoner rehabilitation.

Prisons

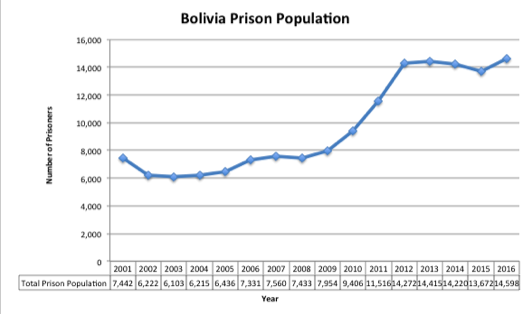

Bolivia incarcerates its population at one of the lowest rates in the Americas.[5] However, the number of people imprisoned is rising steadily: the prison population has doubled since 2005.

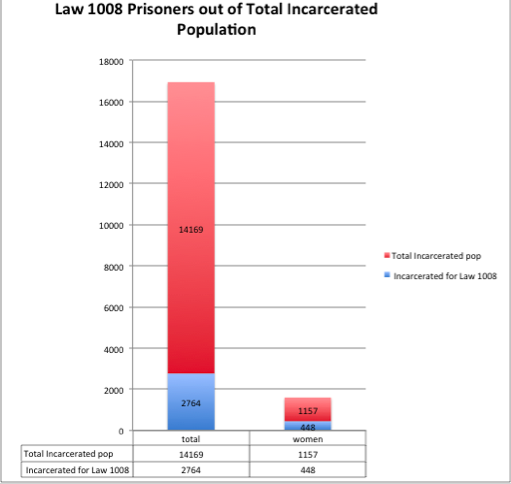

Although steadily declining, twenty percent of prisoners are incarcerated for drug offenses under Law 1008, adopted in 1988 at the behest of the United States.[6]

Bolivia has the second highest rate of pre-trial detention in Latin America after El Salvador and one of the highest in the world with 69% of current prisoners awaiting trial.[8] Most outstanding cases take between two to three years to resolve, and despite reform in 1996, prisoners are rarely released after presenting guarantees that they won’t flee and someone to vouch for them. Pre-trial detention remains deeply entrenched in the judicial system: in Santa Cruz, prosecutors ask for it at 96% of all preliminary hearings. [9]

This results in severe overcrowding, with Bolivian prisons the fifth most congested in the region after Haiti, El Salvador, Guatemala and Venezuela.[10] With a capacity for 5750 prisoners, in July 2016, Bolivia’s 61 facilities (19 urban, 42 rural) held 14,598 prisoners, or 254% over capacity.[11] Tiny cells can house up to 4 people, with only one bed.[12]

The lack of background research about prisoners: who they are in socio-economic and cultural terms, their educational levels and what circumstances led them to commit crimes further impedes prison reform.[13]

Incarcerated Women and Children in Prison

Women make up 9% of the total prison population, the highest in the region, even though this percentage has dropped in recent years even as it has increased in other parts of Latin America.[14]

With only four women’s prisons in the country, women share facilities with men in Riberalta, Montero and Oruro. In other prisons, division between women and men’s facilities is often inadequate, increasing women’s vulnerability. Prisons lack sufficient obstetric and gynecological care.[15] Women also report sexual abuse at the hands of the police and lawyers.

Children frequently accompany their parents in prison, and women also live inside with their incarcerated partners. In 2015 Bolivia’s Human Rights Ombudsman estimated the number of children accompanying parents in Bolivia’s jails fluctuates between 800 and 1,500 children. Although Bolivian law allows children up to age six to live in prisons, many are older.[16] Most children leave to attend school, while younger children remain inside, some at preschool facilities such as the one at San Pedro prison in La Paz.[17]

Cochabamba psychologist Veronica Bustillos runs a program (Centro de Apoyo Integral Carcelario y Comunitario – CAICC) to provide support to children incarcerated with their mothers. She argues that it is less damaging for young children to stay with their imprisoned mothers rather than be separated and institutionalized.[18]

Juvenile Justice

Few facilities exist for juveniles between 16 and 21, which increases the potential for them to suffer abuse while incarcerated.[19] According to Vice Minister of Justice Diego Jimenez, 711 adolescents are currently serving time in Bolivian prisons, and 500 have received alternative sentences. Nearly half of incarcerated youth are in adult prisons. The youth pre-trial detention rate has dropped in recent years to roughly 50%.[20] Nonetheless, a recently proposed anti-gang law cracks down on gang related crimes and could potentially place more juveniles behind bars.

A study at a juvenile detention center near La Paz found that about half of the detainees could have opted for an alternative to incarceration if they had been better informed and represented. Their cases take longer to process and so they suffer a greater retardation of justice than adults. Staff trained to work with juveniles is almost completely lacking. [21]

Some current efforts appear promising. A project, financed by the Departmental government in Santa Cruz, has increased the percentage of juveniles released by a third. Based on this and other initiatives, the Ministry of Justice estimates that 23% of previously incarcerated people commit another crime, but recidivism among people who received alternative sentences is only 1.5%.[22]

Prison Services Fall Short

Nationwide, approximately only 25 doctors, including two psychiatrists, and fourteen social workers work in the country’s 61 prison facilities.[23] Prison authorities report they provided services for 2115 cases in the first half of 2016.[24]

The government allots about $34 a month to cover the costs of food, medicine and personal items per prisoner.[25] This sum forces prisoners to rely on income from family members and/or work. The most common expenses are purchasing a cell (which generally costs several hundred dollars) and paying for paperwork related to a case. Outside the men’s prison San Sebastian in downtown Cochabamba, the street is filled with furniture for sale, made by the prisoners inside

Poor conditions provoke recurring strikes, mutinies and internal conflicts. The most serious led to 35 deaths in 2013 at the country’s largest prison, Santa Cruz’s maximum security Palmasola. A conflict in Cochabamba’s maximum security El Abra prison in 2014 left four people dead. Penitentiary system officials were later convicted of corruption because of the incident.[26]

Internal governance

According to Dan Moriarty, former National Coordinator of Prison Ministry for the Bolivian Bishops’ conference, prisons operate more on a penal colony model than as a modern penitentiary. He explains, “within the prison, inmates are free to move about and interact largely as they please, resulting in a kind of enclosed village with stores, restaurants, sports leagues, cultural activities, and the same socio-economic divisions that mark the world outside. Guards only come into the inner areas of the prison when problems arise, or for a twice-daily roll-call.”[27]

Control is in the hands of inmates themselves who determine how space, food and material goods are distributed, sanctions are applied, who gets legal help, and who suffers retribution. Moriarty calls this a “system of democratic self-governance” that elects representatives to defend prisoners’ interests before authorities and the press. These delegates advocate for prisoners’ needs, organize repairs to the often crumbling and inadequate infrastructure, as well as organizing recreational activities. Inmate tribunals hold trials and punish prisoners who violate community norms, all without calling in the prison’s guards.

Interactions between police officials and inmates are most frequently based on a personalized, rather than rule-based, relationship. There are no specially trained prison guards. A series of informal punishments and rewards, well understood by both police and prisoners, regulate prison interactions.[28] Research by Bolivia’s Human Rights Ombudsman’s Office shows this has fomented bribery and blackmail that involves everyone from judges to prosecutors to the police. “It’s entrenched in the whole apparatus,” says Yolanda Herrera of the Bolivian Assembly on Human Rights.[29] However, there are signs of improvement. As of April 2016, the Ministry of Justice announced that 450 police who work in prisons will be trained in the legal code governing children (Law 548) so that the rights of children who live with their parents in prison will be better protected.[30]

Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation services in Bolivia’s prisons are severely limited, mainly executed through non-governmental organizations and the Roman Catholic Church. The Catholic Prison Ministry works throughout the country, focused on spiritual healing, occupational therapy, legal assistance, social work, especially for families and incarcerated minors, and public advocacy for prisoners’ rights. Other groups are smaller, such as Semilla de Vida, which works in La Paz’s women’s prisons to provide health, education and, economic training so prisoners can earn an income. As of July 2016, 722 women had benefited from Semilla’s drug rehabilitation and social reincorporation plan.

The absence of coordinated rehabilitation fosters recidivism. According to the Catholic Prison Ministry, in Tarija 23% of prisoners go back to prison–the highest rate in the country.[31]

Rehabilitation is squarely on the government’s agenda. “Unfortunately we inherited a penal system that did not value social rehabilitation,” says Government Minister Carlos Romero.[32] The current Director of the Penitentiary system, Jorge López, argues that reintegration must be based on five pillars: education, training, jobs, health, and sports/culture[33] In Santa Cruz, the departmental government initiated a pilot treatment project for juvenile offenders in 2013. Two years later, an Orientation Center was inaugurated to offer alternatives to incarceration for 900 youth by 2017, and Oruro has announced plans to establish a similar center.[34] In Viacha, outside La Paz, a renovated juvenile facility Qalauma, which houses 120 inmates under the age of 25 was opened in 2014 with support from the Italian government and non-governmental organizations. It trains young people in carpentry, sewing, baking, and agriculture. And in March 2016, the development of a new model prison was announced with local, departmental and federal funding in Arani outside Cochabamba.[35]

Moriarty argues that for all its profound problems and human rights violations, aspects of Bolivia’s prisons are more humane than many other countries. Prisoners are less institutionalized because they are not held in barred cells, families are able to stay together, the maximum sentence is 30 years and there is no death penalty.[36]

Police Reform Falters

Government efforts at police reform were met by a violent mutiny in June 2012. Bolivia’s national police force is characterized by a repressive, highly bureaucratic and militarized structure, scarce professional training and low capacity, which results in an informal work structure, as well as high degrees of bribery and corruption.[37] The government concluded that the only people the police serve are themselves.[38]

The uprising in eight of Bolivia’s nine departments was led by police officers’ wives who demanded salary increases for their poorly paid husbands and rejected efforts to establish disciplinary procedures. The police refused to work for six days and burned files investigating police wrongdoing. The MAS government backed down, although it has since dragged its heels in responding to the police demands it agreed to.[39] Police mounted another countrywide protest in 2014, again over salary demands.

Police reform has always been on the MAS agenda, but it couldn’t gain traction until a new Minister of Government, Carlos Romero, took over in 2015. He has managed to build some trust with the police and announced a reform plan based on five pillars: greater specialization, decentralization of police services, increased training, and improved technology. At the end of 2015, the government began a thorough evaluation of the national police with United Nations assistance.[40]

Rocky Road for Judicial Reforms

In 1996, Bolivia passed a Judicial Bond Law that dramatically decreased pre-trial detention rates and the overall incarcerated population. A new criminal procedures code in 1999 created an oral trial system in an effort to reduce judicial delay, and established key due process guarantees, such as the presumption of innocence. The prison population declined as a result, from 8,153 in 2000 to 5,577 in 2001.[41]

However punitive public attitudes led to a gradual weakening of the 1999 reforms, resulting in the return to greater preventive detention, the debilitation of due process, and increased retardation of justice.[42] The presumption of innocence remains weak, and the burden of proof is largely on the defendant as prosecutors generally present little evidence to justify their request for preventive detention. At least 10% of those held before their trials are imprisoned for minor crimes. [43]

The government has undertaken a major, restorative justice reform of the penal code. In effect since January 2016, the previous three overlapping codes governing crime have been merged into one internally coherent one; crimes are differentiated to reduce prosecutor’s involvement in minor offenses; preventive detention is to be the exception rather than rule; and a top heavy, bureaucratic and dysfunctional citizen judge system has been terminated.[44]

The number of judges has steadily increased in recent years, but Supreme Court Judge Fidel Tordoya argued in 2015 that this was only a third of those needed to overcome delays and inadequate geographical coverage.[45] The number of cases per judge increased steadily from 2011 to 2013.[46] Untrained judges are the norm, which partially explains the enormous backlog of cases congesting the judicial system.[47]

The number of Public Defenders has also grown from 84 in 2013 to 100 nationally in 2016,[48] still grossly inadequate for a population of almost 11 million people. However, efforts are underway to reform the judiciary. One significant improvement during the MAS government is an increased increased, if limited, presence of public defenders in rural areas.

In 2015, Bolivia’s Attorney General, Ramiro Guerrero, dismissed 67 of the 500 prosecutors in his office due to accusations of corruption. Another 41 were sanctioned for unacceptable practices.[49] Even though the number of prosecutors has steadily increased, so has their caseload.[50]

Also in 2015, the courts announced that all current cases would be registered through Judicial Registry Database (Sirej) so that citizens could track their cases.[51] A government-called Summit on the Judicial System took place on June 10, 2016 in Sucre with an agenda which focused on access to justice, retardation of justice, corruption of justice system functionaries, lawyers’ training, judicial elections, and a new criminal policy.[52] The summit resolved to conduct performance evaluations for judges and prosecutors over the course of 120 days, implement sanctions for officials guilty of grave offenses, and maintain election by popular vote for high-level magistrates.[53] An implementation commission has formed to carry out these conclusions.

Pre-trial detention had dropped from over 80% of to 69%, even though the rate remains higher than the Latin American average of 56%. [54] Part of the drop can be attributed to the 2014 Penal Decongestion Law, which mandates release except in cases of corruption, femicide, murder, and rape) and when pre-trial detention exceeds 12 months without an accusation or 24 months without a sentence. The Ministry of Justice announced a plan in April 2015 to reduce the percentage to 50% through establishing judicial hearings in prison.[55] Under this initiative forty-three cases reached a verdict in just two days in three prisons in Santa Cruz. A similar effort settled 108 cases in two other prisons.[56] Other proposals to reduce overcrowding include house arrest, prisoner tracking devices and fines instead of prison time for minor crimes.[57]

Amnesty and Pardon Initiatives:

The MAS government has implemented four amnesty initiatives, leading to the release of over 4000 prisoners, with plans to release about 10,000 more according to David Tezanos Pinto, head of the National Public Defenders’ Office and Human Rights Ombudsman. This contrasts with only two pardons in the ten years’ prior (one in 1995 and the other in 2000).[58] Those who have benefited most are women and people held under Law 1008, as well as those who have been held in preventive detention for as long as the maximum sentence for the crime they are accused of. A Supreme Degree (DS 2437) in 2015 granted pardons to women who are more than 24 weeks pregnant, disabled people, and prisoners with terminal illnesses.[59] But in the absence of far reaching reforms in the penal system, new detentions have more than made up for initial reductions in the prison population.

| Amnesty Law | Men Released | Women Released | Total Released |

| Presidential Amnesty Decree #1445

Dec. 19, 2012 |

172 | 62 | 234 |

| Presidential Amnesty Decree #1723

Sep. 18, 2013 |

1221 | 512 | 1733 |

| Presidential Amnesty Decree #2131

Oct. 1, 2014 |

1300 | 398 | 1698 |

| Presidential Amnesty Decree #2437

July 7, 2015 |

1009 | 279 | 1288 |

| Total | 3702 | 1251 | 4953 |

Conclusion:

Prison reform under the MAS government confronts serious hurdles. Especially in big cities, citizens have demanded increased punishment and incarceration for offenders. This has had negative impacts on caseloads in the judicial system and exacerbated the retardation of justice.[60] Nonetheless, the MAS government has demonstrated a commitment to confront institutional problems in the judiciary, police, and prison systems through varied initiatives, including a penal code reform, amnesties, and police training.

Appendix: Major legislation governing Bolivia’s penitentiary system

| Initiative | Description | Impact |

| Judicial Bond Law (1996) | Introduced judicial bail to avoid preventive detention and improve the level of legal and social equality in the penal process, allowed for provisional freedom in certain crimes relating to controlled substances, and established other procedural modifications including the suppression of expert consultations. | Controlled delays in the Judiciary and decreased pre-trial detentions. |

| New Penal Procedural Code, Law 1970 (1999) | Established: a 36-month maximum time for penal procedures and 6-month preparatory time; the exceptional and proportional nature of preventive detention; oral penal procedures; the introduction of citizen (civil) judges; victim intervention into the judicial process and victim reparations; and conventional representation. | Facilitated alternatives to penal proceedings, simplified the penal process, limited punitive powers of the State, and initially decreased the use of pre-trial detention. |

| Citizen Security Law 2494 (2003) | Established recidivism as cause for procedural risk, increased powers of the judge and prosecutor to determine the accused’s risk of flight/obstruction and increased penalties for crimes. | Caused an increase in pre-trial detention and prison overcrowding, and decreased opportunities for alternatives to incarceration. |

| Penal Modification Law 007 (2010) | Determined criteria for risk of flight: prior criminal record; prior formal accusation or sentence; having received alternatives to incarceration; participation in criminal organization; threat to society. Also modified limitations on pre-trial detention. | Caused an increase in pre-trial detention and prison overcrowding, and decreased opportunities for alternatives to incarceration. |

| Penal Decongestion Law (2014) | Established: system for expedited investigations/resolutions for pending cases; ways to convert penal action to private mediation; an end to pre-trial detention in cases where new elements demonstrate that the motives to detain the person were inadequate, when the duration exceeded the legal minimum for the most grave crime the person is being tried for, when the duration exceeds 12 months without an accusation or 24 months without a sentence (except in crimes of corruption, state security, femicide, murder, rape of an infant/child/adolescent, and infanticide), and when the person in pretrial detention has a terminal illness.

|

Pre-trial detention decreased from 85% in 2012 to 69% in 2015. Established legal limitations on the application of pre-trial detentions. However, critics suggest that creating exceptions on these regulations for crimes of corruption, state security, etc. is problematic. |

| Presidential Amnesty Decrees (2012-2015) | Presidential Decree 1445 (Dec. 19 2012),

Presidential Decree 1723 (Sep. 18, 2013), Presidential Decree 2131 (Oct. 1 2014), Presidential Decree 2437 (Jul. 7 2015) |

Freed a total of 4,953 prisoners (75% men, 25% women). One of the highest presidential pardon initiatives in the hemisphere. Nonetheless, the number of total prisoners in Bolivia has not gone down. |

*Special thanks to Julia Yanoff of the Andean Information Network for input and graphics.

[1] Preventive detention is also called pre-trial detention, but in the Bolivian case, the first term is more appropriate as those accused are incarcerated ostensibly to prevent them from committing more crime. Ramiro Orias A. 2015. Prisión Preventiva en Bolivia. Fundación del Debido Proceso. Apr 6. http://dplfblog.com/2015/04/06/prision-preventiva-en-bolivia/

[2] http://www.laprensa.com.bo/diario/actualidad/la-paz/20130124/siete-de-cada-10-mujeres-sufren-violencia-en-el_42221_67781.html

[3] “Latin Americans Least Likely Worldwide to Feel Safe.” Gallup. Aug. 2012. http://www.gallup.com/poll/156236/latin-americans-least-likely-worldwide-feel-safe.aspx

[4] Latin American Public Opinion Project (LAPOP). 2014. Cultura política de la democracia en Bolivia, 2014: Hacia una democracia de ciudadanos. http://www.vanderbilt.edu/lapop/bolivia/AB2014_Bolivia_Resumen_Ejecutivo_W_082115.pdf p. 28.

[5] Brienen, M. 2015. A Special Kind of Hell: the Bolivian Penal System in Rosen, Jonathan D. and Marten W. Brienen, editors. 2015. Prisons in the Americas in the Twenty-First Century: A Human Dumping Ground. Lexington Books. p. 151.

[6] Peru and other governments adopted similar hardline laws demanded by the U.S.

[7] Dirección General de Régimen Penitenciario, 2016, July.

[8] This percentage has dropped 15% since 2010. LAPOP, 2014. P. 16; Open Society Foundation. 2014. Presumption of Guilt: The Global overuse of Pre-trial Detention. https://www.opensocietyfoundations.org/sites/default/files/presumption-guilt-09032014.pdf p. 19.

[9] Orias, Ramiro, Susana Saavedra y Claudia V. Alarcón. 2012. Reforma Procesal Penal y Detención Preventiva en Bolivia. P. 225.

[10] CNN. 2016. A qué se debe el aumento de mujeres presas en América Latina? http://cnnespanol.cnn.com/2016/11/03/a-que-se-debe-el-aumento-de-mujeres-presas-en-america-latina/

[11] El Deber. 2016. Población carcelaria no para de crecer en Bolivia. Mar 9. http://www.eldeber.com.bo/bolivia/poblacion-carcelaria-no-crecer-bolivia.html

[12] Fundación Construir. 2014. Prisión preventiva y Derechos Humanos en Bolivia. http://www.fundacionconstruir.org/index.php/documento/online/id/95 p. 44.

[13] Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos. 2012. Uso abusivo de la prisión preventiva en las Américas. Informe presentado en el 146° período de sesiones de la Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos (Washington, DC, 1 de noviembre de 2012). http://www.fundacionconstruir.org/index.php/documento/online/id/63

[14] Boiteux, Luciana. 2015. The Incarceration of Women for Drug Offenses. The Research Consortium on Drugs and the Law (CEDD). http://www.drogasyderecho.org/publicaciones/pub-priv/luciana_i.pdf

[15] Situación de derechos humanos de las mujeres privadas de libertad en Bolivia. 2013. Comisión Interamericana de Derechos Humanos (CIDH). http://ojmbolivia.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/Informe_CIDH2013.pdf

[16] http://www.interiuris.org/archivos/situacioncarceles.pdf p. 42.

[17] Shahriari, Sara. 2015. In Bolivian prisons, blood is thicker than Bars. Jan 12. http://america.aljazeera.com/multimedia/2015/1/in-bolivia-bloodisthickerthanbars.html

[18] El país de los niños encarcelados http://elpais.com/elpais/2015/06/09/planeta_futuro/1433849917_678211.html

[19] Giné Ariscaín, Carla, coordinator. 2005. Jóvenes privados de libertad; entre el anonimato y el abandono institucional. La Paz: PIEB.

[20] Los Tiempos. 2016. Sugieren aplicar justicia restaurativa en menores. http://www.lostiempos.com/actualidad/nacional/20161014/sugieren-aplicar-justicia-restaurativa-menores

[21] Fundación Construir. 2014. Op. cit. P. 17-21; 35.

[22] Ministry of Justice. 2016. El Ministerio de Justicia y UNICEF presentaron documentos sobre adolescentes en conflicto con la Ley y el sistema penal especializado. http://www.justicia.gob.bo/index.php/noticias/notas-de-prensa/2086-el-ministerio-de-justicia-y-unicef-presentaron-documentos-sobre-adolescentes-en-conflicto-con-la-ley-y-el-sistema-penal-especializado

[23] La Patria. 2015. Alrededor de 25 médicos atienden a 13.200 privados de libertad. http://www.lapatriaenlinea.com/?t=alrededor-de-25-ma-dicos-atienden-a-13-200-privados-de-libertad¬a=242019

[24] López, Jorge. Aspectos Generales del Régimen Penitenciario. PowerPoint. July 9, 2016.

[25] El País. 2015. http://elpais.com/elpais/2015/06/09/planeta_futuro/1433849917_678211.html

[26] Carvajal, Ibeth. 2016. Anuncian ampliación del penal de El Abra. La Razón. http://www.la-razon.com/seguridad_nacional/Cochabamba-anuncian-ampliacion-penal-El_Abra_0_2416558358.html

[27] http://danmoriarty.blogspot.com/2013/06/closing-san-pedro-prison.html

[28] http://www.defensoria.gob.bo/sp/datos_personas_privadas_libertad.asp

[29] Dorado Nava, Cecilia. 2015. La Iglesia desnuda drama carcelario y apela al papa. El Deber. Apr 29. http://www.eldeber.com.bo/bolivia/iglesia-desnuda-drama-carcelario-y.html

[30] Agencia Boliviana de Información. 2016. Justicia capacitó a 454 policías en la Ley 548 para proteger derechos de niños que viven en cárceles. Apr 6. http://www.abi.bo/abi/?i=347348

[31] Arnéz, Pamela. 2015. Pastoral Penitenciaria: Crecen casos de reincidencia por falta de políticas de rehabilitación y reinserción laboral

[32] Farfán, Williams. 2015. Qalauma, un ejemplo para la rehabilitación. Jul 7. http://www.la-razon.com/seguridad_nacional/Centro-Qalauma-ejemplo-rehabilitacion_0_2303169704.html

[33] López. 2016. Op. cit.

[34] Hoy Bolivia. 2015. Gobernación inaugura Centro Especializado en Orientación y Reinserción Social. Jan 7. http://hoybolivia.com/Noticia.php?IdNoticia=133495&tit=gobernacion_inaugura_centro_especializado_en_orientacion_y_reinsercion_social; La Patria. 2015. Adecúan centros de rehabilitación juvenil a normativas actuales. Sept 11. http://www.lapatriaenlinea.com/index.php/somos-noticias.html%3Ft%3Del-dia-de-la-mujer-boliviana%26nota%3D44370?nota=232635

[35] ERBOL. 2016. Garantizan 15 has en Arani para una cárcel modelo. http://www.erbol.com.bo/noticia/regional/09032016/garantizan_15_has_en_arani_para_una_carcel_modelo

[36] http://danmoriarty.blogspot.com/2013/06/closing-san-pedro-prison.html

[37] Campero, José Carlos. 2012. El motín policial en Bolivia en junio de 2012. Friedrich Ebert Foundation. http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/la-seguridad/09539.pdf

[38] Ortiz, Pablo. 2015. La Policía es la última rebelde que le huye a las reformas de Evo Morales. El Deber. May 31. http://www.eldeber.com.bo/especiales/policia-ultima-rebelde-le-huye.html

[39] Chávez, Eduardo. 2013. De 10 puntos conseguidos por el motín policial, sólo uno se cumple. La Razón. Apr 8. http://www.la-razon.com/nacional/seguridad_nacional/puntos-conseguidos-motin-policial-cumple_0_1811218867.html

[40] Farfán, Williams. 2015. ONU ayuda a elaborar diagnóstico de la Policía. La Razón. Dec 19. http://www.la-razon.com/seguridad_nacional/Estudio-ONU-ayuda-elaborar-diagnostico-Policia_0_2402159807.html

[41] Yáñez Cortés, Arturo. 2012. La reforma procesal penal de Bolivia(1). La Razón. Apr 20. http://www.la-razon.com/index.php?_url=/suplementos/la_gaceta_juridica/reforma-procesal-penal-Bolivia1_0_1599440106.html; Brienen. Op. cit. P. 158.

[42] Ramiro Orias A. 2015. Op. cit.

[43] Fundación Construir. 2014. Op. Cit. P. 17-18.

[44] Farfán, Williams. 2014. Cambio al sistema penal busca restar casos a la Fiscalía. Mar 17. http://www.la-razon.com/index.php?_url=/nacional/seguridad_nacional/Cambio-sistema-restar-casos-Fiscalia_0_2016398353.html

[45] Fundación Construir. 2014. Op. cit. P. 17; Numbela, Martín. 2015. Piden triplicar número de jueces e incrementar presupuesto. Opinion. July 28. http://www.opinion.com.bo/opinion/articulos/2015/0728/noticias.php?id=167024

[46] Fundación Construir. 2014. Ibid. P. 10.

[47] Ministerio de Justicia: existen 516.000 procesos en mora. Erbol. Nov 29. http://www.erbol.com.bo/noticia/seguridad/29112015/ministerio_de_justicia_existen_516000_procesos_en_mora

[48]Suárez, Carol. 2015. Defensa Pública atendió 18.000 causas en 2014. La Estrella del Oriente. http://www.laestrelladeloriente.com/index.php?option=com_k2&view=item&id=16759:defensa-publica-atendio-18-000-causas-en-2014&Itemid=721; Telephone interview with Servicio Nacional de Defensa Pública, Sept 29, 2016.

[49] Flores, Yuri. 2016. Ministerio Público destituye a 67 fiscales por irregularidades. La Razón. Jan 16. http://www.la-razon.com/nacional/Ministerio-Publico-destituye-fiscales-irregularidades_0_2415958438.html

[50] Fundación Construir. 2014. Op. cit. P. 11.

[51] Los Tiempos. 2015. Informatizan los registros judiciales. Jul 15. http://www.lostiempos.com/diario/actualidad/nacional/20150714/informatizan-los-registros-judiciales-_308360_682241.html

[52] Paredes Tamayo, Iván. 2016. Evo traza seis ejes para cumbre judicial en Sucre. Jan 23. http://www.eldeber.com.bo/bolivia/evo-traza-seis-ejes-cumbre.html

[53] Correo del Sur. 2016. Cumbre judicial aprueba cadena perpetua y evaluación a jueces. http://correodelsur.com/seguridad/20160612_cumbre-judicial-aprueba-cadena-perpetua-y-evaluacion-a-jueces.html

[54] Los Tiempos. 2016. Baja número de personas con detención preventiva. http://www.lostiempos.com/actualidad/nacional/20160114/baja-numero-personas-detencion-preventiva

[55] Condori, Iván. 2015. Justicia busca reducir 50% de juicios de presos preventivos. La Razón. Apr 28. http://www.la-razon.com/seguridad_nacional/Proyecto-justicia-reducir-juicios-presos-preventivos_0_2261173900.html

[56] Erbol. 2015. En 2 días logran 43 sentencias en 3 carceletas cruceñas. Jul 14. http://www.erbol.com.bo/noticia/seguridad/14072015/en_2_dias_logran_43_sentencias_en_3_carceletas_crucenas

[57] Pomacahua, Pamela. 2015. Proponen multas para delitos menores. Página Siete. Jul 15. http://www.paginasiete.bo/nacional/2015/7/15/proponen-multas-para-delitos-menores-63254.html

[58] Cusicanqui Morales, Nicolás. 2008. El indulto en la legislación boliviana. http://www.monografias.com/trabajos-pdf/indulto-legislacion-boliviana/indulto-legislacion-boliviana.pdf

[59] Alanoca, Jesús. 2015. Aprueban amnistía por visita del papa Francisco. El Deber. Jul 7. http://www.eldeber.com.bo/papa/aprueban-amnistia-visita-del-papa.html

[60] Orias et al. 2015. Op. cit. P. 226.