Here’s our analysis of the Bolivia section of this report in collaboration with Gabriela Reyes. Download report.

1) UNODC says: “In Bolivia, political turbulence in late 2019 & the recent challenges related to the spread of COVID-19 appear to be limiting the ability of state authorities to control coca bush cultivation, which could lead to an increase in cultivation.”

2) UNODC says: “In Bolivia the sociopolitical conflicts of Oct/Nov 2019 had already affected the coca leaf market & cocaine production, the premature withdrawal of the eradication task groups caused a reduction in eradication compared w/the previous year.” Well, not exactly

3) It’s important to distinguish btw legal coca markets & leaves for the illegal trade. This skews their analysis. The 2019 eradication goal was 10,000 hect., the annual total fell short by 795 & is still greater than the Añez gov’ts 2020 goal (8,525). https://bit.ly/2YN6sjN

4) Forced eradication renewed on Feb. 14, 2020 until the COVID state of emergency. There is not a direct correlation between eradication and overall coca crops, must consider replanting, new planting &, shifting dynamics.

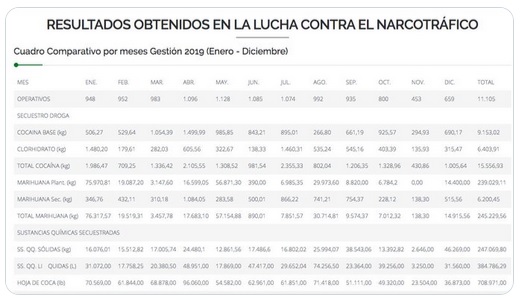

5) The correlation between Bolivian coca crops and cocaine production and trafficking in the country is even more circuitous—a significant portion of cocaine paste comes from Peru, and is transhipped to Brazil & other countries or processed into HCL and exported. It’s important to note that interdiction of cocaine paste & HCL continued during 2019 social unrest & the current quarantine, with seizures similar to preceding year.

6) The interim gov’t has tried to block coca sales for licit use: a) A failed attempt to close the legal Sacaba market (Chapare production) in mid-Nov., according to the officials stationed there. b) Closure of the Chuquiaquillo market in La Paz, used by many licensed farmers.

7) The gov’t also attemped to take over and limit licensing for Yungas coca growers, especially those affiliated with MAS, which eroded farmer trust and heightened tensions there.

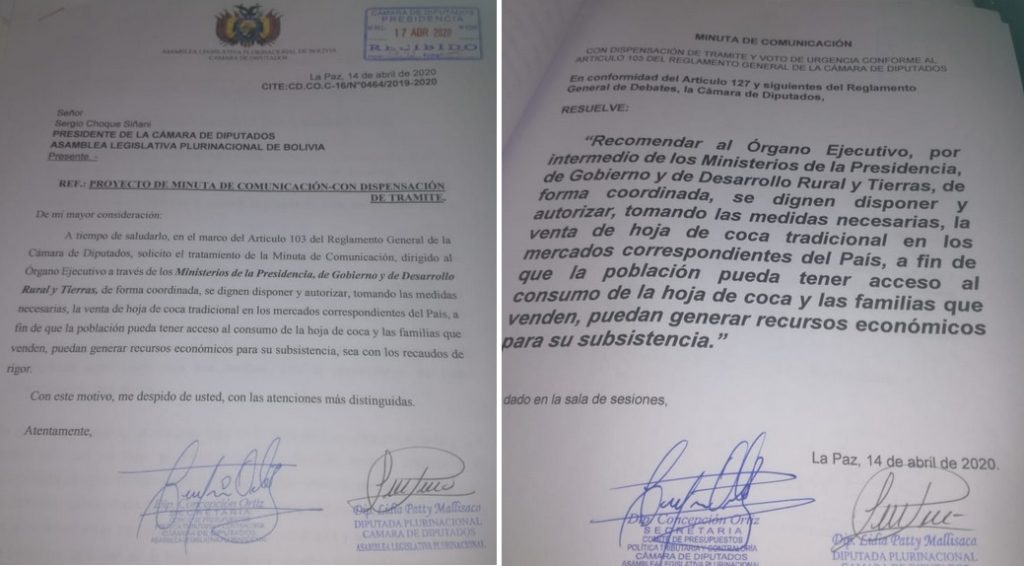

8) The prohibition of legal coca sales during the quarantine, even with needed permits, threatens farmer subsistence at a time of acute economic crisis. Representatives from all region request the right to renew sales with State supervision.

9) UNODC says:“After Nov. 2019, the “Social Control” approach, adopted earlier was abandoned and the states were placed in charge of regulating the number of coca producers $ the area of their plantations, and adopted their own rationalization or eradication measures.” Hmm

10) According to Bolivia’s 2017 General Coca Law 906, the social control program remains in place, which implicates state control in coordination with coca growers organizations. Farmers in both the Chapare and La Paz Yungas continue to affirm their commitment to the program.

11) UNODC says: “Conversely, in Bolivia, the political turbulence at the end of 2019 & the COVID-19 crisis at the beg. of 2020 could be facilitating farmers to relax the social enforcement of 1 cato of coca cultivation per family, possibly leading to an increase in cultivation.”

12) Farmers continue to affirm their commitment to the social control model, which has received international recognition. They’ve been met with repressive State actions, such as the massacre of 9 Chapare farmers and the injury of over 100, by the security forces in November 2019.

13) The freeze on int. development projects put the coca control program at risk. COVID exacerbates this, especially w/the punitive ban on gasoline sales in the Chapare, bankrupting EU-funded aguaculture projects which use gasoline pumps to aerate ponds. https://bit.ly/2YGFE4W

14) #COVID creates significant economic challenges in coca growing areas, but history shows that repressive government policy, stigmatizing farmers, presents the most corrosive risk for increased cultivation in national parks and areas where coca growing is illegal.