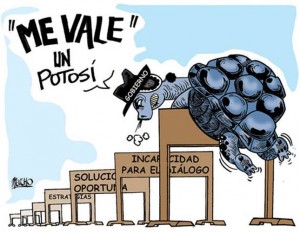

Urban Potosí, once the richest city in South America, is now one of the poorest. A mining center during the colonial and post-colonial eras, economic progress has been slow in recent decades and the region remains largely isolated with poor infrastructure. Previous administrations did little to promote development in the region. Campesino and working-class social movements, many originating from this department, contributed to the victory of Bolivian president Evo Morales, himself a social movement leader. Seventy-eight percent of Potosí voters chose Morales in the 2009 presidential elections, second only to voters in the La Paz department. However, recent conflicts in Potosí and in other parts of the country demonstrate that many social movements interpret their support of Morales as a right to directly pressure his administration to keep his electoral promises and address the long-postponed, swelling expectations of the grassroots that elected him. In short, although protests reflect diminishing support for Morales, their intensity also demonstrates citizens’ sense that the current administration should be more accountable to its constituents than its predecessors from traditional political parties.

Broad-based popular support

For two weeks, civic groups have shut down the city of Potosí and many surrounding regional roads, demanding that the national government complete promised projects in the region. Potosí natives living in La Paz, Cochabamba, and Sucre are also staging solidarity protests. Morales officials blamed mobilization on Potosí Mayor, Rene Joaquino and the “rightwing opposition.” Yet, unlike regional demands, which reflected clear class and political partisan divisions in Sucre in 2008, in fact the majority of the department’s residents support the movement. Even MAS-affiliated Potosí governor, Felix Gonzalez, and MAS senator Eduardo Maldonado joined a hunger strike of thousands of miners, union workers, prostitutes and other actors, sending a clear signal to the national government that it must meet six key demands:

1. the installation of a cement factory in Coroma, Potosí

2. construction of an international airport

3. the preservation of the dilapidated Cerro Rico, once a metal-rich mining center and a city landmark

4. completion of a metals processing plant in Karachipampa

5. the consolidation and completion of regional road infrastructure.

6. demarcation of disputed territorial boundaries with neighboring Oruro[i]

Conditions delay dialogue

Oscar Coca, Minister of the Presidency, announced on August 9 that the national government could negotiate the first five points in Potosí and the last, which defines departmental borders, in Sucre, since it is of national concern. He also offered direct dialogue with President Morales in La Paz if protests ended, causing greater tension in the region. On August 11, Potosí civic leaders announced they would meet with Morales in Sucre, but refused to deescalate protests. They cut power to the San Cristobal mine and threatened to block more roads and start a march from Potosí to La Paz if the government fails to respond.

Concessions deemed insufficient, protests drag on

The Bolivian Executive announced plans to fund $577 million of construction projects for schools, roads, and other infrastructure in the region, but civic leaders demanded a time line for long-promised airport construction. Meanwhile, blockades and closed banks exacerbated food supply and cash flow shortages in urban Potosí. Doctors ordered the evacuation of Governor Gonzalez for medical attention as a result of his participation in the hunger strike. Some foreign tourists remain stuck in the city as a result of blockades. The French and Argentine embassies are pressuring the Bolivian government to rescue their citizens, some of whom need medical attention. Meanwhile, the United Nations office in Bolivia has called the lack of access to educational facilities and needed supplies in Potosí human rights violations, urging the government to settle the dispute.

Mounting domestic demands

It is unclear if Morales will meet with Potosí leaders. He has just returned from in South Korea to negotiate lithium extraction policies and plans to go to Paraguay on August 14 to discuss diplomatic relations. His intense international travel agenda provokes criticism that he fails to prioritize domestic demands. Furthermore, it seems paradoxical that a government of social movement leaders, who frequently staged similar protests, has proven unable to provide an agile strategy to address current conflicts. Without a clear plan for negotiations protracted protests, tensions could escalate, although Morales officials have announced that they will not send police or military to lift the blockades. The eventual outcome of the current regional crisis will condition future popular demands throughout the nation. High expectations for widespread social change, public works and basic services continue to mount, presenting perhaps the most significant challenges in Morales’s second term.

_______________________________________

[i] Disputes over department boundaries frequently occur because government funding to regions is determined on a per capita basis. This particular dispute also concerns the boundaries of a limestone-rich mining site that could be used for the cement processing plant in Coroma.