On October 11, coca growers in the North Yungas region of the La Paz department organized blockades to protest a recent Bolivian government measure to limit and control coca leaf production and sales. Nine days later on October 19, protestors signed a preliminary agreement with the government and lifted blockades until November 5, allowing for dialogue in this intermediate period. Although the longstanding causes of the current conflict are linked to MAS initiatives to legally limit coca in the region, the temporary resolution has an infinitely simpler explanation: October 20 is the anniversary celebration of Coroico, home to many protestors.[i]

Protestors rejected a clause in the Coca Commercialization Regulation (August 13, 2010) that reduced the legal limit for growers’ direct coca sales from 15 to 5 pounds per month. The Morales administration previously conceded these direct sales to coca growers, but is now moving to restrict the amount, in response to international pressure.

The Coca Commercialization Regulation would reduce farmers’ personal income. Currently, coca growers make greater profit by directly selling their coca quota to consumers rather than to legal market intermediaries. This new policy coincides with other Morales administration measures attempting to restrict and control illicit coca leaf sales, and ongoing government plans to increase oversight in the Yungas region, which houses the majority of Bolivia’s coca crop. Nevertheless, implementation of these initial steps incurred predictable opposition in the Yungas.

Although the Morales administration annulled the new restrictions in favor of further dialogue, protestors initially refused to lift blockades unless government officials came to them to negotiate additional demands. The Departmental Association of Coca Producers (ADEPCOCA), the union leading the protest, claims that nearly 6,000 demonstrators participated in several locations. On October 14 tensions rose, as protestors began to throw rocks at parked vehicles trapped by the blockades for several days. Two days later, transportation unions with stranded drivers initiated counter-protests, prohibiting their members from giving supplies to coca growers involved in the blockades. Migrants loyal to MAS in the spillover coca-growing region beyond the blockades also threatened to dismantle the barriers.

This conflict exacerbates historic divisions among coca growers’ unions throughout the country, and reveals the inherent difficulty of maintaining equilibrium among disparate coca growing regions. Demonstrations also provide a preview of likely conflict when the Bolivian government adjusts the 12,000-hectare limit for coca production in the traditional zone.

“Traditional” vs. “illicit”

Under previous administrations little opportunity existed to modify policy through open dialogue between coca growing federations and the Bolivian government. President Morales continues to head the Six Federations of Chapare Coca Growers, and rose to power in large part thanks to their collective support. However, these ties do not guarantee his popularity among all factions in the La Paz coca growing territories. The delineation of coca growing regions in Law 1008, the 1988 edict that restricted “traditional” and “illicit”[ii] coca production in Bolivia, arbitrarily forced regional competition between Chapare federations and the Yungas coca growers:

Article 9. The traditional coca production zone is that in which coca has been historically, socially and organically cultivated to serve traditional uses… In this zone only the necessary volume to meet the demand for licit consumption and use… will be produced.[iii]

The law also geographically limited the “traditional” area to the subtropics of the North and South Yungas of La Paz, as well as the Yungas of Vandiola in the Cochabamba department, and capped production at 12,000 hectares without any statistical basis to determine legal demand within Bolivia.[iv] Yungüeños continue to use Law 1008 to justify increasing coca cultivation as their historical right. At the same time, this legislation marginalized the Chapare coca-growing region and other spillover zones as “illicit,” and required gradual eradication in those areas.[v]

Chapare coca growers thus resent the protection granted to their Yungas rivals. They perceive that farmers in the traditional zone directly benefited from violent forced eradication in the Chapare between 1997 and 2004. This situation ostensibly allowed the Yungas to grow a great deal more coca without any governmental consequences, considerably exceeding the 12,000-hectare limit set by Law 1008. Ex-dictator Banzer attempted forced eradication in the Yungas in 2001, and immediately failed as a result of unified coca grower protests. No administration before Morales successfully eradicated more than 40 hectares per year in that region. Yet, according to the latest UN coca cultivation study on Bolivia, “the La Paz Yungas produced 68 per cent of the total [coca] cultivation for 2009,” much of which exists within the boundaries of the traditional zone.[vi]

Although new control measures seem overdue in light of the government’s longstanding responsibility to limit production in compliance with international accords, the Yungüeños now feel unfairly targeted by the Morales administration, which they believe is allied with the Chapare. “There is inequality. It could be that, because our brother, Evo Morales, is from the Chapare, he prefers [that region]. We [Yungas] coca growers feel like stepchildren, while the Chapare is [treated like] the preferred son,” commented Tiburcio Mamani, a ADEPCOCA representative.[vii]

Chapare coca growers also accuse the Yungas of receiving support from the U.S. government, revealing long-standing mistrust and reflecting the struggles of the Chapare region to overcome historical repression under previous antinarcotics strategies.

Conflicting coca confederations

Shifting divisions among the Yungas coca grower organizations further complicate this tense situation. Unlike the Six Federations of the Chapare, Yungas growers are not a unified force. Some coca growers in the Yungas traditional zone historically allied with conservative political parties, such as MIR, whereas colonizers in spillover zones generally are more willing to participate in MAS coca control policies.[viii] ADEPCOCA, the traditional growers’ force leading the protests, vehemently distinguishes its members from a rival umbrella organization, the Council of Yungas Rural Farmers’ Federations (COFECAY). Increasing recent tensions, the latter group met with MAS officials to decide the terms of the coca reduction agreement. Spillover zones within the Yungas region are currently undergoing cooperative coca reduction, with mixed results. Ironically, some of the traditional coca growers maintain plots of land in the spillover Yungas zones. Conflicts also overlap when municipal governments compete and different political groups disagree.

Two days before ADEPCOCA decided to instigate protests, President Morales fueled friction by openly sided with COFECAY, calling it “the strongest and most legitimately recognized” Yungas coca growing organization.[ix]

Traditional zone growers’ demands

As protests continued, despite initial government concessions, ADEPCOCA presented a rapidly swelling list of nine to eleven demands. Their petitions included dismissal of several high-ranking MAS officials, construction of a hospital for coca growers in La Paz, a coca processing plant, and the relocation of one UMOPAR (a counter-narcotics police force) base to Unduavi, as well as road repairs and other public works projects throughout the region. ADEPCOCA leaders met with a group of MAS legislators in the Yungas on October 14, with no resolution.

The union has also called for the removal of Minister of Government, Sacha Llorenti, the Minister of Rural Development, Nemesia Achacollo, the Vice Minister of Social Defense, Felipe Caceres, the Vice Minister of Coca and Development, German Loza, and other functionaries. ADEPCOCA accuses these MAS officials of negotiating the terms of the coca reduction agreement with leaders without consulting their organization. MAS Senator Fidel Surco, in charge of a group legislators sent to meet with protestors on October 15, commented that it would be difficult to satisfy demands to fire MAS appointees because, “then when any blockade happens, they could ask for the head of any vice minister.”[x]

Head of ADEPCOCA, Ramiro Sanchez, differentiated between President Morales and the rest of his government: “It’s not President Morales’s responsibility… that there are dishonest ministers and disloyal vice ministers. [Those officials] have imposed commercialization regulations on the Yungas overnight, and I believe that the people will not forgive [these measures]. As a result, we have asked for their removal.”[xi]

Sanchez also aligned the ADEPCOCA protests with other recent blockades instigated by groups that traditionally supported the MAS government: “I believe that the Yungas region has been too quiet, we’ve been too calm, but today it’s our turn. [The government] has already [intervened] in the Potosi department and then in Caranavi.”[xii]

Vice President Garcia Linera responded to the protestors on October 13, stating that, “The regulation was already annulled, and therefore there is no justification for the blockade. The primary point [of contention] was already overcome, and ministers… have already been called on to work with [the protestors] to elaborate a new regulation… Please lift the blockade and come to dialogue together with your leaders.”[xiii]

Strategic location of blockades

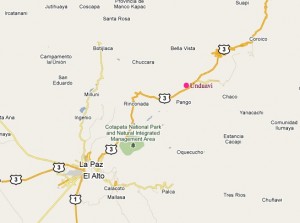

The blockades occurred between Unduavi and Santa Barbara, less than 50 miles from La Paz. A coca regulation checkpoint is located at Unduavi, which likely explains the decision to stage protests there. Road obstruction at that point also effectively blocks all traffic in and out of the Yungas region, and to the Beni and Pando departments. Residents of areas isolated by the blockades, including coca-producing migrants to the spillover zone and MAS supporters, began voicing concerns on October 18, threatening to confront the ADEPCOCA protestors if they don’t cease their demonstrations. Ultimately, this pressure contributed to the temporary resolution of blockades.

A difficult balance

Existing friction runs much deeper than the protesters’ recent lists of demands. Coca growers throughout Bolivia are also concerned about the forthcoming publication of the EU-funded, Integrated Coca Market Study to determine the demand for licit and traditional coca use. The Morales administration maintains that the results of this survey will inform revision of the legally permitted coca production limits, as part of broader Law 1008 reforms.

In the Chapare and Yungas spillover zones, previously identified under Law 1008 as areas of illicit production, the current policy permits a small amount of legal coca production (one cato, or 1600 square meters). This measure guarantees farmers’ subsistence, while capping growth to keep the price high and limit cultivation. The MAS government set the existing nation-wide production ceiling at 20,000 hectares. In 2004, Morales and other coca grower leaders agreed to adjust this limit to reflect the results of the legal market study, a promise that the Bolivian government says it will keep.

At a meeting of the Chapare coca growers’ federations on October 16, President Morales’ union constituents demanded larger plots for legal coca production, complaining about the limitations of the cato system. Denying their request, Morales cautioned union members to avoid selling their coca leaf for cocaine production. “If this detour didn’t exist, it would not be necessary to fight against drug trafficking. The challenge is to eradicate [excess] coca, while respecting human rights,” Morales asserted.[xiv] The recent Yungas protests revive Chapare coca growers’ frustrations, highlighting their overall submission to enforcement of the cato limit, while Yungas farmers continue to stonewall government policy and increase their coca crops.

Conclusions

Recent conflicts also beg the question, what would be an equitable method to determine regional boundaries and limitations for coca production? There are several recommendations for a fresh approach:

“To work in the traditional zone, we need new legislation. Once that comes out, we could maintain the 12,000 hectares in the Yungas… There are three ways to distribute [these hectares]… One is to let the growers decide, something that will never happen. They’re not going to be able to accomplish the impossible. The second is to define a quantity per farmer. If we distribute a half-hectare [per coca grower] we arrive at 12,000 [total]. The third [option] is to use the first UNODC crop monitoring study as a baseline, which showed about 12,000 hectares in Yungas. This would permit farmers the amount of hectares they had [at the time of the study]. This would allow us to still privilege the traditional growers.… Or, you could set a limit that no one could have a hectare, and those who had more should reduce [their plot]. In the traditional area there could not be any unmeasured extensions, especially because the ecosystem won’t permit it. The earth there is very poor and even coca doesn’t grow well.”[xv]

Implementation of any new regulations will certainly meet opposition in the Yungas region, which has long benefited from its “traditional” coca growing status. Policy reform will doubtless be a long, conflict-ridden process subject to international pressure. Although it is important that both the Bolivian government and protestors negotiate and compromise, divided Yungas coca growers should also recognize that they are facing a window of opportunity to influence lasting reform with a government that understands and attempts to guarantee coca farmers’ subsistence. It is unlikely that any future administration would be as sympathetic to their concerns as the Morales administration has been.

[i] In addition to coca production, tourism represents a significant source of income for the Coroico municipality.

[ii] Law 1008 actually refers to the Chapare as a “transitional” zone, meaning it should be subject to eventual coca reduction and eradication. Effectively, this earmarked all coca produced in that region as illicit.

[iii] ARTICULO 9. La zona de producción tradicional de coca es aquella donde histórica, social y agroecológicamente se ha cultivado coca, la misma que ha servido para los usos tradicionales, definidos en el artículo 4º En esta zona se producirán exclusivamente los volúmenes necesarios para atender la demanda para el consumo y usos lícitos determinados en los artículos 4º y 5º Esta zona comprenderá las áreas de producción minifundiaria actual de coca de los subtrópicos de las provincias Nor y Sud Yungas, Murillo, Muñecas, Franz Tamayo e Inquisiví del Departamento de La Paz y los Yungas de Vandiola, que comprende parte de las provincias de Tiraque y Carrasco del Departamento de Cochabamba.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] ARTÍCULO 10. La zona de producción excedentaria en transición es aquella donde el cultivo de coca es resultado de un proceso de colonización espontánea o dirigida, que ha sustentado la expansión de cultivos excedentarios en el crecimiento de la demanda para usos ilícitos. Esta zona queda sujeta a planes anuales de reducción, sustitución y desarrollo, mediante la aplicación de un Programa Integral de Desarrollo y Sustitución; iniciando con 5.000 hectáreas anuales la reducción hasta alcanzar la meta de 8.000 hectáreas anuales. La concreción de estas metas estará condicionada por la disponibilidad de recursos financieros del Presupuesto Nacional, así como por compromiso y desembolsos de la cooperación técnica y financiera bilateral y multilateral suficiente, que deberá orientarse al Desarrollo Alternativo. Esta zona comprende las provincias Saavedra, Larecaja y Loayza, las áreas de colonización de Yungas del departamento de La Paz y las provincias Chapare, Carrasco, Tiraque y Araní del departamento de Cochabamba.

ARTÍCULO 11. La zona de producción ilícita de coca está constituída por aquellas áreas donde queda prohibido el cultivo de coca. Comprende todo el territorio de la República, excepto las zonas definidas por los artículos 9º y 10º de la presente ley. Las plantaciones existentes de esta zona serán objeto de erradicación obligatoria y sin ningún tipo de compensación.

[vi] UNODC, “Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia: Monitoreo de Cultivos de Coca 2009.” June 2010.

[vii] Erbol, “Yungueños: Evo nos trata como a hijastros y los del Chapare son hijos preferidos.” 17 October 2010.

[viii] Dr. Caroline Conzelman, an expert on the Yungas region, also differentiates between coca growers based near Coroico, in the more “traditional” zone, versus Caranavi, the newer “spillover” zone mostly populated by colonizers. Conzelman explains that Coroico is deemed “elitist” due to its historical protection under Law 1008. Furthermore, Caranavi residents perceive that Coroico benefits unfairly from international NGO support and disproportionate tourist traffic. Conversely, Caranavi believes it suffers economically, despite USAID projects and support.

“El Movimiento Cocalero en los Yungas de Bolivia: Diferenciación Ideológica Económica y Política.” In N. A. Robins, ed., Conflictos Políticos y Movimientos Sociales en Bolivia. La Paz: Plural Editores, 2006.

[ix] ABI, “Morales no justifica bloqueo de caminos en Los Yungas por un tema resuelto con productores de coca.” 9 October 2010.

[x] La Razon, “Cinco días de bloqueo a Yungas y no hay solución.” 15 October 2010.

[xi] Los Tiempos, “3er dia de bloqueo de ruta en Yungas.” 13 October 2010.

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] Los Tiempos, “Gobierno plantea a cocaleros elaborar nuevo reglamento para suspender bloqueo.” 13 October 2010.

[xiv] Los Tiempos, “Morales afronta rebelión de los cocaleros.” 18 October 2010.

[xv] AIN-IPS-PIE Interview with Karlos Hoffmann, Proyecto de Apoyo de Control Social de la Producción de Hoja de Coca. 9 August 2010.