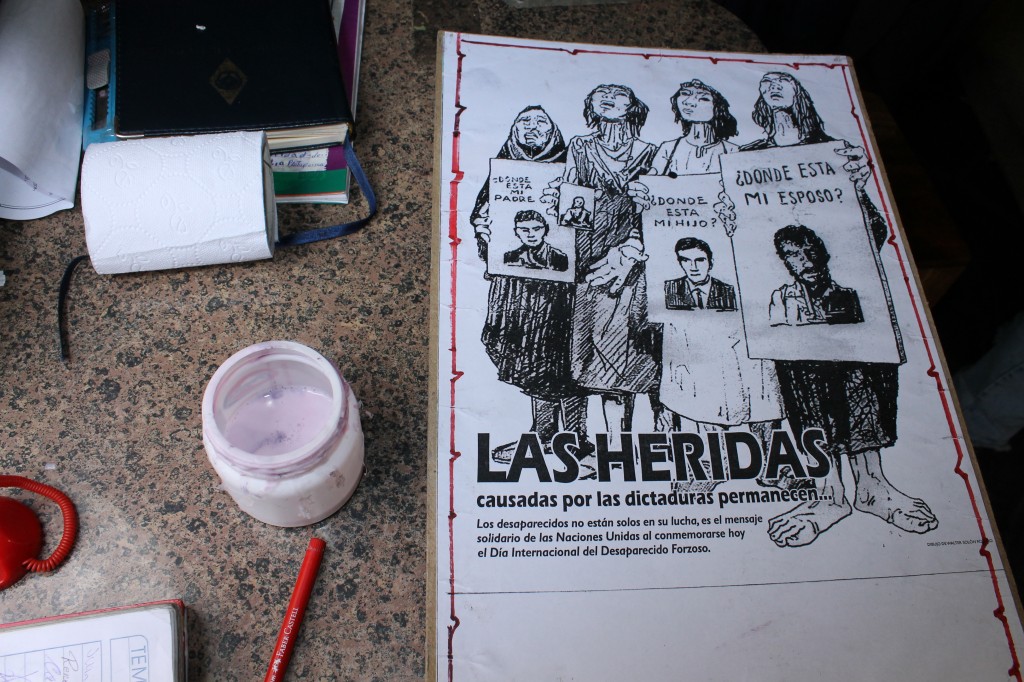

“The wounds caused by the dictatorships remain…”

“The wounds caused by the dictatorships remain…”

Photo credit: Gonzalo Ordoñez for AIN

Bolivia has had more military coups than any other nation in the world. Hugo Banzer (1971-1978) and Luis García Meza (1980-1981) were the most notorious Bolivian dictators in the Twentieth Century. More than 30 years after restoration civilian rule, however, victims of political violence still await justice. Unlike neighboring Chile and Argentina, which initiated some legal action against those involved, impunity continues in Bolivia. The military has refused access to documents from the dictatorship years; successive administrations have made minimal effort to pressure the military and have dragged their feet on the reparation process.

Julio Sevilla on a march with Bolivian Workers Central (COB); “30 years of martyrdom”

Julio Sevilla on a march with Bolivian Workers Central (COB); “30 years of martyrdom”

Photo credit: Gonzalo Ordoñez for AIN

A group of dictatorship survivors has camped out in front of the Ministry of Justice building since March 13, 2012. The group, the Platform of Advocates Against Impunity and for Justice and Historical Memory of Bolivian Dictatorship Survivors, demands the reparations promised to survivors of the dictatorships under a law passed in 2004, access to military documents from the dictatorship years, and an end to impunity for human rights violations.

The Platform’s headquarters, located on the Prado in La Paz

The Platform’s headquarters, located on the Prado in La Paz

Photo credit: Gonzalo Ordoñez for AIN

Inside the headquarters

Photo credit: Gonzalo Ordoñez for AIN

“We are not going to give up. They think, ‘Okay, these old folks are going to die,’ and we have already had two losses. It doesn’t matter. There are members who say, ‘We’ll die here. This is our last battle, and we’re going to win, of that you can be certain.’” – Dr. Jorge Pelaez Rivero, Platform member

“184 days of vigil”

Photo credit: Gonzalo Ordoñez for AIN

The victims of the Banzer dictatorship have been waiting over 40 years for acknowledgement of the violence they suffered. Most of the Platform members have been politically active for decades, but began the vigil as a result of the most recent round of protracted legal impediments to economic compensation mandated by Bolivian law.

The Platform marching with COB; “Platform of Advocate Against Impunity and for Justice and Historical Memory of the Bolivian Dictatorship Survivors”

The Platform marching with COB; “Platform of Advocate Against Impunity and for Justice and Historical Memory of the Bolivian Dictatorship Survivors”

Photo credit: Gonzalo Ordoñez for AIN

President of the Platform Julio Llanos Rojas explains their frustration:

“The world knows about these crimes against humanity…the United Nations, through human rights organizations, sanctions states to ensure that these acts never occur again. In Argentina and Chile, they have already complied with this obligation, however in not in Bolivia. Why? Because there is no political will for this. They want to cover it up; they are covering up the dictators. They do not want to sanction the torturers who raped, the coercive agents. Because of this, tired of all the mockery, we started a vigil on March 13, 2012…The government does not uphold the law. They are victimizing us again, they are violating our rights, and because of this we will continue…”

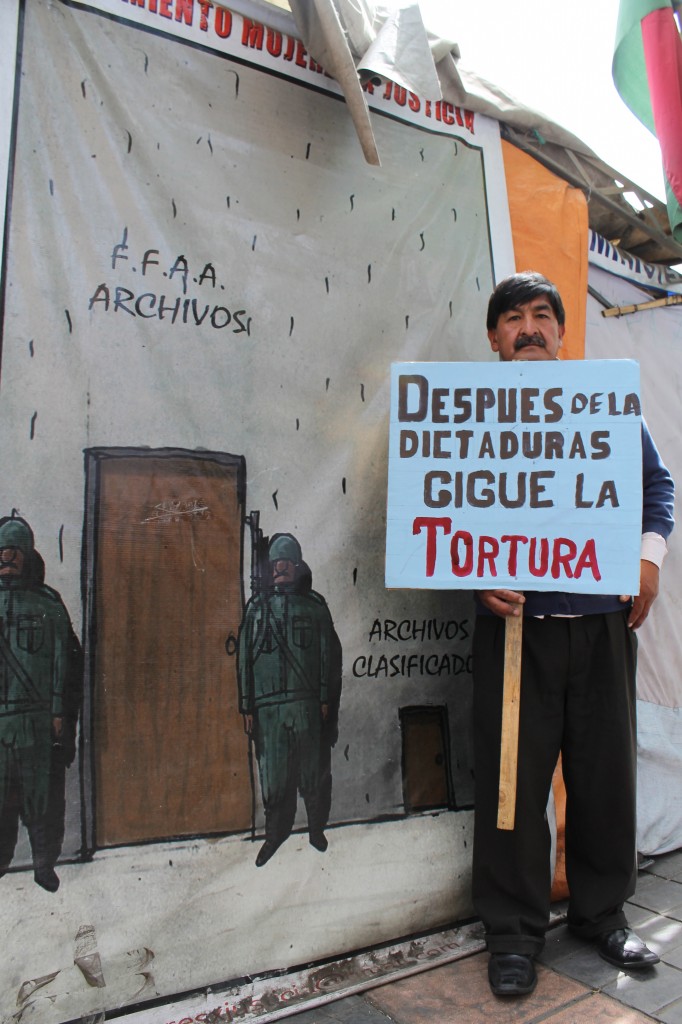

Luis Hernan Cornejo, Secretary; “After the dictatorship, the torture continues.”

Luis Hernan Cornejo, Secretary; “After the dictatorship, the torture continues.”

Photo credit: Gonzalo Ordoñez for AIN

Legislature

- In 2004, the Bolivian legislature passed Law 2640, which did the following:

- Granted economic compensation, as well as free medical and psychological care, medicine, and medical equipment to victims of the dictatorship;

- Established that victims of torture, forced disappearance, death, exile, political persecution, detention and arbitrary imprisonment, and injury qualified for benefits; and

- Established a budget for the reparations:

- 20% of the $3.6 million (USD) from the National Treasury — $1.2 million a year of from 2005 to 2007

- 80% from donations from the private sector, international organizations, and foreign entities.

However, Law 2640 was not been upheld. Economic compensation was supposed to be completed by 2007. In 2005, the government published a list of names, but did not disburse any funds to them.

- In 2006, the government passed Law 3449, which disbanded the reparation commission and established a new one that was supposed to carry on the work of the first one, but the new commission started the process from scratch.

- In 2007, the government passed a supreme decree, just before the legal deadline for compensation, which:

- Extended the timeline for the government to pay economic compensation;

- Changed the standards of evidence, making it extremely difficult to prove acts of violence. For example, the decree required rape and torture victims to present medical certificates to document the abuses- — something physically impossible.

The absurdity of this requirement is not lost on the Platform members; Dr. Pelaez noted:

“When you are being tortured, you can’t ask the torturers to bring in a witness.” The government asked women for medical certificates for rapes that occurred over 41 years ago, which are “are impossible to obtain” according to Dr. Pelaez; “They have asked for exit and entrance visas…from colleagues who had to secretly leave the country and return clandestinely…Their intention is to erase what happened before 2003…to them, history just began in 2003.”

Victoria Lopez, General Secretary; “184 Days of Vigil”

Victoria Lopez, General Secretary; “184 Days of Vigil”

Photo credit: Gonzalo Ordoñez for AIN

By 2012, some 8,000 survivors had applied for reparations.

- On April 30, 2012, the government passed a new law, Law 238, and then passed a supreme decreeon May 1, 2012 to regulate Law 238. This legislation:

- Approved only 1,714 of the 8,000 survivors who applied;

- Declared the government would provide $3.6 million USD, 20% of the $18 million USD promised in the original law; and

- Set compensation to a minimum of 26.70 Bolivianos per day of violence suffered, a paltry $3.84 USD. The maximum pay per day of violence is 134.04 Bolivianos, approximately $19.26 USD.

The most recent legislation obligates the government to disburse only 20% of the original amount stipulated in the previous law, with no commitment to seek the rest of the $14.4 million USD from the private sector and foreign entities as promised in the 2004 law. The 2004 law set a higher maximum compensation limit, based on a formula using calculations from 60 to 300 minimum salaries (depending on the length and extent of violence), while the maximum compensation under the 2012 legislation is based on calculations from 60 minimum salaries for all victims.

The Platform marching with COB; “Platform of Advocates Against Impunity and for Justice and Historical Memory of the Bolivian People Survivors of the Dictatorship”

Photo credit: Gonzalo Ordoñez for AIN

“It’s ridiculous; it’s humiliating,” Llanos expressed. “It’s a pittance, and because of this, many people rejected this pay and sent letters of the Minister [returning the checks. There is a general discontent among those who qualified [to receive reparations].”

In addition, the Platform estimates that the great majority of more than 35,000 dictatorship victims will not receive any compensation –the state only deemed 1,714 eligible. Many victims did not know about the law or missed the deadline to apply. As violations of human rights and crimes against humanity, these actions “should not have a expiration date,” according to Llanos.

Dr. Jorge Pelaez Rivero marching with COB

Dr. Jorge Pelaez Rivero marching with COB

Photo credit: Gonzalo Ordoñez for AIN

“More than anything else,” said Dr. Peleaz, the Platform asks that the Morales administration “respect our dignity as victims of political violence…not one of us has thought, ‘Oh, they’re going to give me money, so I’ll join the struggle.’”

For the Platform members, the fight for justice goes far beyond the money. It is about recognition from the government about the history of violence and brutal repression, for which their former torturers never received legal consequences.

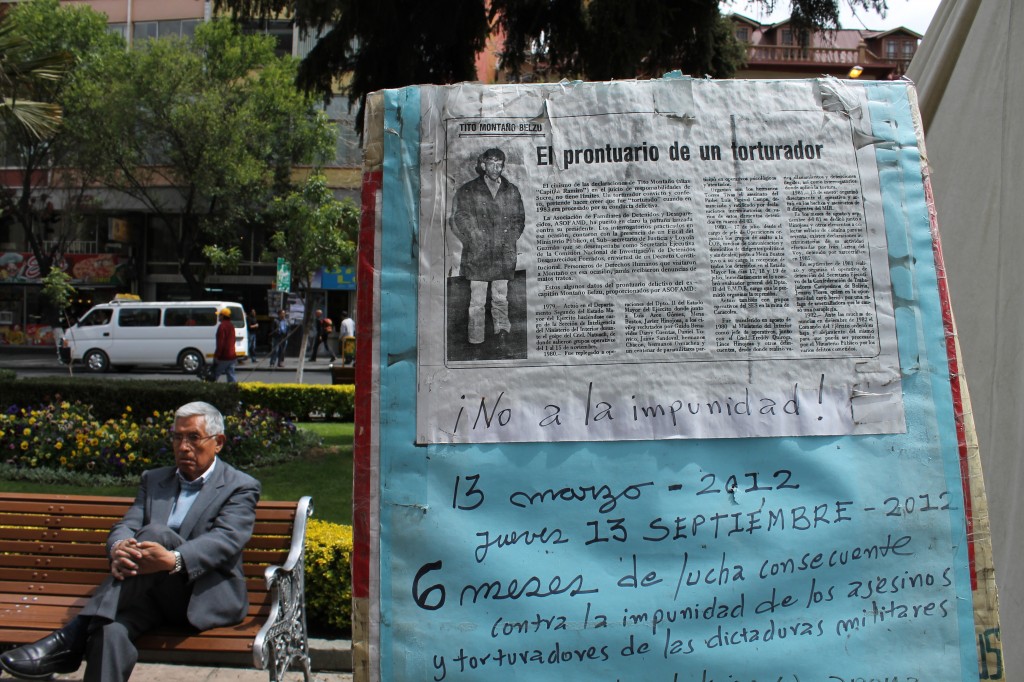

Newspaper headline: “The record of a torturer;” Written note: “No to impunity! March 13, 2012 – Thursday, September 13, 2012: Six months of consecutive fight against impunity of murderers and tortures of the military dictatorships”

Newspaper headline: “The record of a torturer;” Written note: “No to impunity! March 13, 2012 – Thursday, September 13, 2012: Six months of consecutive fight against impunity of murderers and tortures of the military dictatorships”

Photo credit: Gonzalo Ordoñez for AIN

The refusal of the military to provide access to documents from the dictatorship, and the government’s corresponding lack of pressure on the military to do so, has been a persistent barrier to ending impunity to human rights violators in Bolivia. (Please see AIN updates Bolivian Military Stalls and Pressures Civilian Authorities in Human Rights Investigation and Bolivian Armed Forces Block Investigation of Dictatorship Deaths for further analysis.) Without the cooperation of the military and stronger political will from the government, the cycle of impunity for human rights violations will continue in Bolivia.