Some are more equal than others:

U.S. “decertification” of Bolivia’s Drug Control Efforts

Kathryn Ledebur and Julia Romani Yanoff

Andean Information Network

September 21, 2016

In its annual Presidential Determination[1], the U.S. “decertified” Bolivia’s drug control efforts for the ninth consecutive year, since 2008, when the Bolivian government expelled the U.S. ambassador and the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration. As Bolivian coca production holds steady at the lowest rate in the region, without widespread conflict, and the country strengthens regional antidrug cooperation efforts, the U.S.’ unilateral “F” grade for Bolivia appears contrived and unconvincing.

In response, the New York Times Editorial Board observed, “the yearly condemnation of Bolivia has been futile. So far, that country’s experience with its drug strategy is showing more promise than Washington’s forced-eradication model.” The merits of Bolivia’s unique coca control model have been lauded by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), The Organization of American States (OAS), the European Union, researchers, and drug policy reform advocates.

The Memorandum of Justification outlines Bolivia’s noncompliance with “international counternarcotics agreements” using inconsistent, selective, standards. A closer look at key complaints demonstrates that the U.S. continues to overlook its own criteria for certification, in favor of an apparently political determination, based on accordance with U.S. drug control dictates.

Although U.S. domestic drug reform has made progress, international policy, focused on forced crop eradication, including the ‘certification system,’ is obsolete and arrogant. It is time for the U.S. to abandon this system and objectively analyze Bolivia’s efforts.

How does Bolivia match up to U.S. drug control standards? See for yourself with AIN’s point-by-point analysis of selected U.S. arguments:

- Violation of International Counternarcotics Agreements: the U.S. sites violation of the 1961 UN Single Convention on Narcotics Drugs as an example of Bolivia’s “demonstrable failure”:

“Bolivia continues to promote the use of coca in other countries by not prohibiting the export of coca leaf (prohibited by the 1961 UN Single Convention) for consumption by Bolivians residing in Argentina and discussing potential export opportunities for coca products with other countries.”

Bolivia withdrew from the convention in 2011 and then re-acceded to it with a reservation on prohibitions to traditional coca use in 2013, in order to protect the historical and customary use of coca in Bolivia. The re-accession was approved by the majority of UN member states.

Moreover, Peru’s state coca agency Enaco, formally promotes coca exports. Its mission is “to be the only legally recognized company in the world, providing coca leaf and industrialized products for national and international markets.” Its motto is to “work to defend traditional coca uses and offer the benefits derived from it to the world.” In 2015, Enaco exported approximately $6.5 million USD in coca, including to the U.S. Although its export of the leaf to the Stepan Chemical Company for use in Coca-Cola is technically legal under a loophole in the UN Single Convention, other exports are not. You can even purchase Peruvian coca leaves in the United States online.

Enaco’s Delisse Pure Coca Powder, “From Cuzco to the World”. Buycocaleaves.com

By its own yardstick, the U.S. would have to “decertify” itself. The March 2016 UN International Narcotics Control Board report chides the U.S. for violation of the same 1961 Single Convention: “measures taken in various states of the United States to legalize the production, sale and distribution of cannabis for nonmedical and non-scientific purposes are inconsistent with the provisions of the international drug control treaties.”

- Coca Reduction: The Memorandum cites Bolivia as one of the largest producers of coca leaf and claims:

“the U.S. government—using different methodology—estimates that coca leaf cultivation increased in Bolivia to 36,500 hectares in 2015, representing a 15-year high.”

In contrast, the United Nations International Narcotics Control Board affirmed in March 2016: “for the fourth consecutive year, the Plurinational State of Bolivia reported a decrease in the area of coca bush cultivation. In 2014, the area of coca bush cultivation fell to 20,400 hectares which was 11 percent less than in 2013 and the lowest level since 2001.” (p. 64)

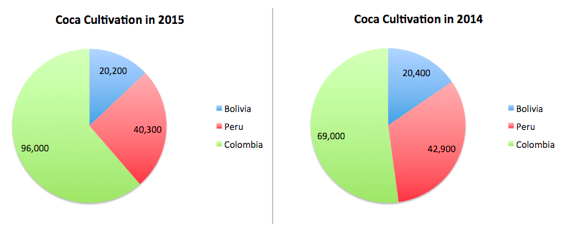

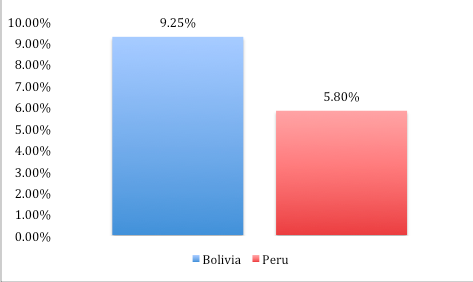

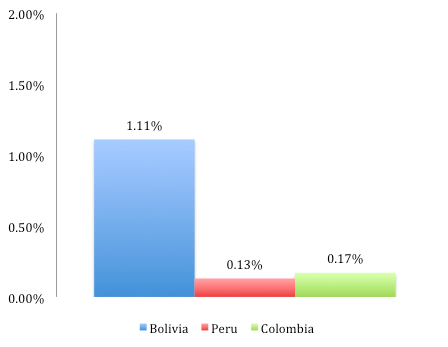

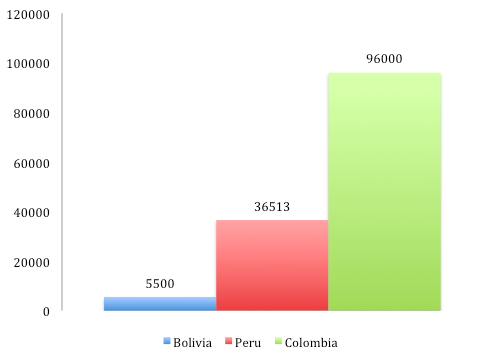

Similarly, in its 2015 Coca Monitoring Survey, the UNODC reports that the amount of coca produced in Bolivia has reduced by a net of 10,700 hectares since 2009 (from 30,900 to 20,200). On the other hand, coca cultivation in Peru is twice the amount as in Bolivia (40,300). In Colombia, it is three times as high (96,000 hectares) and has increased in recent years.

Coca cultivation in the Andes 2015 vs. 2014 according to UNODC statistics

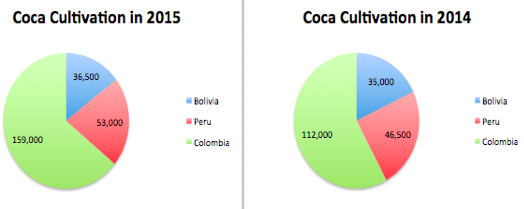

Even according to the U.S. government’s own estimates, Bolivia produces 16,500 hectares less than Peru and 122,500 hectares less than Colombia (Bolivia 36,500, Peru 53,000, Colombia 159,000). Nonetheless, the US continues to “certify” Colombia and Peru.

Coca Cultivation in the Andes 2015 vs. 2014 according to U.S. ONDCP

- The U.S. uses a “Different Methodology”

Beginning in 2012, U.S. coca monitoring figures coincided with the UNODC methodology as a result of close collaboration between Bolivia, the U.S. and Brazil coca monitoring through a trilateral agreement. During this time period, the UNODC and U.S. government published the same coca production figures. The 2014 International Narcotics Control Strategy Report (INCSR) explained that through this agreement, “the United States provided computer and digital measuring equipment as well as training to Bolivian personnel.” According to the 2015 U.S. INCSR, “while the project has formally ended, Bolivia continues to use the digital equipment that the United States provided to measure coca cultivation more efficiently and accurately.”

Inexplicably, in 2014, after the formal end of the accord, and the departure of its key proponent at the U.S. embassy, the ONDCP published dramatically different figures, citing a 40% jump in Bolivian coca production from 2012-2014, which it attributed to a “different methodology.” Initially, 2013 figures were not available on their site. In August 2016, a 2013 figure appeared (27,000) and an additional increase of around 4% was cited for 2015 (to 36,500 hectares).

U.S. officials have provided little public explanation. The U.S. Embassy in La Paz asserts that U.S. methodology is “excellent” and its “images used to estimate coca cultivation are of the best quality and definition, cover a broader territory and are obtained during a longer period of time.”

Bolivian drug control officials affirm to AIN that they are willing to continue to collaborate on coca monitoring, but U.S. officials claim they do not have access to the information.[2] U.S. potential cocaine production statistics are also inherently problematic and present substantial contradictions.

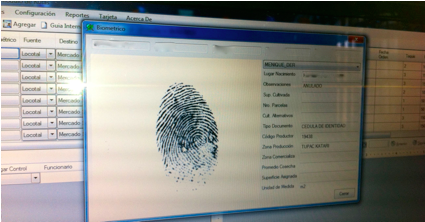

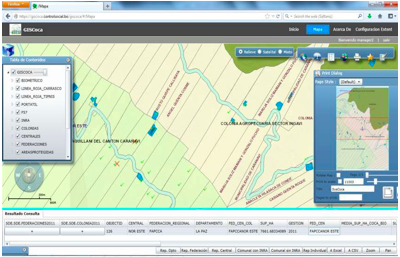

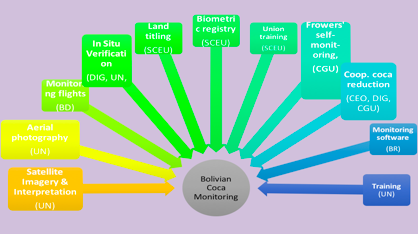

In stark contrast, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime Bolivia coca monitoring report, financed by the European Union and Denmark, includes an 18-page description of its methodology. Joint UNODC-Bolivian government methodology has received widespread recognition. For example, an April 2016 United Nations Development Program report prepared for the General Assembly Special Session on drugs affirmed, “UNODC shared geo-referenced aerial photography and satellite imagery and accompanying analysis, and carries out joint in situ verification missions with Bolivian authorities…a sophisticated database SISCOCA cross-references coca cultivation, land titling and the biometric registry of authorized growers and traces coca leaf transport and sales. Precise collaborative monitoring and ground verification provides reliable crop estimates to implement policy.” With European Union funding, coca growers and Bolivian government agencies also participate in this effort.

The memo also claims “There is little data on the potency of Bolivian coca, crop yields, and cocaine production in the country.” Indeed it is not clear how the U.S. government conducts on the ground coca monitoring and cocaine yield studies since the DEA’s expulsion in 2009.[3] However, the UNODC calculates a range of potential coca yields by region using the 2010, Average Productivity Study of the Bolivian coca leaf, a 2005 UNODC study from the La Paz Yungas, and Chapare baseline data from the DEA (p. 1). The Morales administration has agreed to carry out new yield studies in the coming year.

SISCOCA Screen Shot

SISCOCA Screen Shot

[4]

[4]

- Control over Internal Coca Market: The Memorandum affirms that Bolivia:

“should also strengthen efforts to stem the diversion of coca for cocaine processing by tightening controls over the coca leaf trade.”

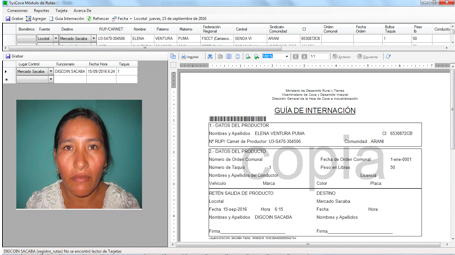

Yet, Bolivia has the most up to date, detailed system in the region. A 2006 law cites specific, multiple requirements for coca sales, licensing, transport and purchases. The Bolivian government’s SISCOCA database tracks the transport of the coca leaf through the licit market. Licensed coca merchants pay high fees to purchase the leaf and sell it throughout the nation. The Morales administration plans to complete a biometric registry of coca merchants by mid-2017 to further strengthen the system.

Although Bolivia most recently updated its biometric registry system for growers in mid-2016, Peru maintains a farmer registry from 1978, with 25,159 licensed farmers growing 17,016 hectares. The Peruvian government does not permit its modification, citing international drug control treaties.[5]

Cultivamos con Responsabilidad (p. 67)

Cultivamos con Responsabilidad (p. 67)

- Drug Seizures/Interdiction Programs: The Memorandum also recommends that Bolivia should:

“improve law enforcement and judicial efforts to investigate and prosecute drug-related criminal activity.”

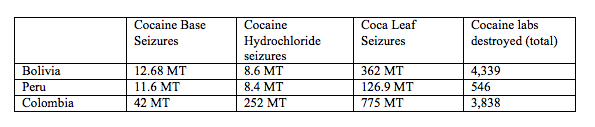

Nonetheless, the number of interdiction missions in Bolivia has steadily increased during Morales’ tenure. In August 2016, Bolivian policed seized 7.5 tons of cocaine near the Chilean border. The Bolivian government incinerates drug seizure with UNODC supervision using ovens donated by the German, British and French governments. The Bolivian antidrug force updates its seizure and arrest data monthly. The U.S. government’s most recent INCSR, cites that in 2015 the Special Force to Fight Drug Trafficking, FELCN (Elite Antidrug Police Force) arrested 3,227 people for narcotics offenses, seized 362 MT of excess coca leaf, 12.68 MT of cocaine base, 8.6 MT of cocaine hydrochloride, and destroyed 105 cocaine hydrochloride processing labs and 4,234 rustic cocaine labs.

Although Peru produces greater quantities of coca and cocaine, in 2015 Peru only seized 126.9 MT of coca leaf, 11.6 MT of cocaine base, 8.4 MT of cocaine hydrochloride, and destroyed 546 total cocaine labs. Dinandro, the FELCN’s Peruvian counterpart has not posted statistics since 2014. Colombia, in proportion to its significantly higher level of cocaine production, has seized 252 MT of cocaine hydrochloride, 42 MT of cocaine base, 775 MT of coca leaf and destroyed 3,838 cocaine labs.

Cocaine Seizures out of Total Potential Cocaine Production (Metric Tons) According to U.S. 2015 Statistics (INCSR and ONDCP)

Cocaine Seizures out of Total Potential Cocaine Production (Metric Tons) According to U.S. 2015 Statistics (INCSR and ONDCP)

Coca Leaf Seizures out of Total Coca Leaf Production (Metric Tons) according to INCSR/UNODC 2015 Statistics

Coca Leaf Seizures out of Total Coca Leaf Production (Metric Tons) according to INCSR/UNODC 2015 Statistics

- Deviation to Illegal Market: According to the Memorandum:

“65 percent of the coca produced in Bolivia is sold through local legal markets; the rest is unaccounted for and likely diverted for illicit purposes.”

According to a 2013 Bolivian government study, funded by the European Union, 14,705 hectares of coca fulfill domestic consumption demands. Although cocaine and cocaine paste seizures demonstrate diversion of the leaf to illegal markets in all three countries, the amount of Bolivian coca leaf transformed into cocaine is significantly lower than for its neighbors. At current levels of coca cultivation, only 5,500 hectares of Bolivian coca are cultivated for the illicit market, or using the 12,000 hectare ceiling established in Law 1008, 8,200. In contrast, in Colombia, due to low levels of traditional consumption, the significant majority of 96,000 hectares of coca produced end up as cocaine, and in Peru 35,791 hectares of coca out of a total of 40,300 hectares goes into the illegal market.[6] The amount of coca deviated into illegal drug trafficking in Bolivia is 1/6th that of Peru, and 1/19th that of Colombia. Bolivia has less illegal coca cultivation than its neighbors.

Coca Deviated to Illegal Markets (hectares) based on 2015 UNODC Reports

Coca Deviated to Illegal Markets (hectares) based on 2015 UNODC Reports

The report’s assumption that “UNODC officials have noted that 95% of coca grown in the Chapare region is not used for traditional consumption and that 89% of the coca grown in the Chapare region did not make it to the legal market in 2015” is not supported by the data.

The UNODC study stated that between 9-13 percent of coca grown in the Chapare entered the legal Sacaba market.[7] The study also affirmed that overall licit coca sales in Bolivia increased by seven percent from 2014, in spite of a 1% overall reduction in the coca crop. Furthermore, coca entering the Sacaba market increased 19% from 2014, in spite of a 2% reduction in coca production in the Chapare area. The situation is far more complex than the Memorandum suggests.

- Bolivia Fails to Cooperate with Neighbors on Drug Control:

“Increased Bolivian counternarcotics cooperation with other countries and in international fora would be welcome.”

Yet, Bolivia actively cooperates in the region on drug control, and participates twice annually in international drug control meetings with UN Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Organizations of American States, Inter-American Drug Abuse Control System (CICAD). As active members of both organizations, the US government is well aware of this participation. During, the April 2016 CICAD meetings in Washington, US officials also had bilateral meetings on coca control with Bolivian representatives. Bolivia also participates in drug control meetings of Union of South American Nations (UNASUR), and the Community of Latin American States (CELAC).

The report erroneously claims that: “during 2015 Bolivia signed counternarcotics cooperation agreements with Peru and Paraguay, it previously negotiated agreements with Argentina in 2002 and Brazil in 1978. Bolivia and Chile also maintain limited cooperation on counternarcotics despite their ongoing dispute over access to the Pacific Ocean. The present impact of these agreements is unclear.”

Yet, Bolivia has actively engaged its neighbors on drug control. For example, in 2016 Bolivia has already signed bilateral agreements with Peru, Brazil, and most recently Argentina on drug control cooperation, including joint border patrol operations, intelligence exchange, precursor control, and coca monitoring, despite the opposing political orientations of their new administrations.

Since 1977, Bolivia has signed eight bilateral accords with Brazil, in addition to the trilateral “Pilot Project for an Integrated Control System for the Reduction of Excess Coca Cultivation” agreement between Brazil, Bolivia, and the U.S. signed in 2012, which President Obama himself lauded saying, “the recent agreement between the U.S., Brazil, and Bolivia to go after (excess) coca cultivation in Bolivia is the kind of collaboration we need.”

The most recent accord with Brazil, signed in June of 2016, and then joined by Peru, called for joint drug interdiction operations, collaborative border patrol, intelligence exchanges, and the provision of technical support for coca monitoring. Furthermore, Bolivia has enjoyed substantial cooperation with the European Union and the United Nations in implementing drug control operations, research, and community development programs since the departure of the Drug Enforcement Administration in 2009. (See Appendix for a list of Bolivian drug control agreements).

In 2012 the Bolivian and Chilean governments agreed to a pilot border control program, using a vehicle scanner donated by the Chinese government.

- Transit Hub: The Memorandum criticizes Bolivia for being a “major transit country for Peruvian coca.”

Nonetheless, Peru has not been decertified for producing cocaine base or allowing it to leave its territory. A 2015 video shows how the Peruvian military allowed drug flights to take off unhindered from the Apurimac Ene Mantaro River Valley (VRAEM), a key coca growing area. Increases in cocaine paste prices in Bolivia, stimulate traffickers to transport significantly cheaper Peruvian paste, through Bolivia to consumer and transit nations (Brazil and Argentina).

- Illegal drug trafficking flights: The Memorandum states:

“The air bridge between Peru and Bolivia is a pressing issue that calls for improved cooperation between the two countries.”

Yet, regional efforts to control drug flights have been ongoing for the last two years. Regional and bilateral intelligence has identified drug flights originating in or through Bolivia to Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay. A two-year intelligence exchange initiative between the Bolivian and Peruvian antidrug polices tracing planes at their landing has led to the seizure of 39 drug planes by the Bolivian forces in 2015.

In an explicit effort to address the air bridge, Bolivia finalized a $200 million contract with French company, Thales, for the purchase, installation and training of 4 air defense radars, 3 primary/approach and 6 secondary civil radars that will substantially improve Bolivia’s control over its airspace.

In 2014, Bolivian Congress adopted legislation allowing its forces to shoot down planes that refuse to respond to orders to land. In March 2016, the Bolivian Air Force announced plans to purchase 7-9 fighter planes for training to intercept drug flights. These shoot-down policies are risky and can provoke human rights violations.

- International [Dis]approval: The Presidential Determination claims that there is a:

“growing international consensus that counternarcotics programs must be designed and implemented with the aim of improving the health and safety of individuals while preventing and reducing violence and other harmful consequences to communities.”

And yet, the U.S. condemnation is out of step with the international community in its stance on Bolivia. In May 2016, the UNODC Deputy Director, Aldo Lale-Demoz, highlighted the “long-term productive collaborative relationship between the Bolivian government and the UNODC.” The UNODC representative for Bolivia, Antonino de Leo, has lauded Bolivia’s continuous reduction in coca cultivation since 2010. In August of 2015 he said “I wanted to congratulate the Plurinational State [of Bolivia] for its continuous reduction in coca cultivation, and to highlight that in the last four years the area of coca cultivation in Bolivia reduced by 10,600 hectares which is more than a third of the amount of coca cultivated in 2010.”

The European Union has also continuously supported Bolivia’s coca reduction efforts. Former European Union delegation chief, Timothy Torlot stated in August of 2015: “I congratulate the Bolivian Government, the Police, and the FELCN) for the policy’s success, it is a great achievement to continue reducing coca production in the country.” His successor affirmed in September 2016, “I ratify the European Union’s support for Bolivia’s progress in the shared drug control model, that respects its international commitments. The new National Drug Control Council (CONALTID) center is yet another symbol of the President’s efforts, and we decidedly support them.”

Conclusion

Although Bolivian drug control is far from perfect and faces multiple challenges the small nation has demonstrated significant political will, resources, and creativity to address the evolving, complex threats of illegal drug trafficking, through both sustainable development goals, a stated UNGASS objective, as well as U.S. “body count” indicators focused on coca cultivation, arrests and seizures. Often Bolivia’s performance surpasses its “certified” coca-producing neighbors.

It’s high time U.S. policymakers abandon their Drug War report card program and reform punitive, ineffectual international drug policies that, not only have failed to limit the drug trade, but have also eroded the U.S.’ credibility with the international community.

Appendix

Bolivia Regional Bilateral Counternarcotics Agreements (non-exhaustive) since 1977

| Year | Countries | Content |

| 1977 | Bolivia-Brazil | Reciprocal Assistance Agreement to Repress Illicit Drug Trafficking |

| 1988 | Bolivia-Brazil | Additional Protocol to the Reciprocal Assistance Agreement to Repress Illicit Drug Trafficking |

| 1990 | Bolivia-Ecuador | Agreement for Prevention of Use and Repression of Illicit Trafficking of Controlled Substance |

| 1990 | Bolivia-Ecuador | Agreement to Prevent Deviation of Specific Controlled Substances |

| 1991 | Bolivia-Uruguay | Agreement for Prevention of Use and Repression of Illicit Trafficking of Controlled Substances and Specific Precursor Chemicals |

| 1991 | Bolivia-Paraguay | Reciprocal Assistance Agreement for the Prevention of Use and Repression of Illicit Drug Trafficking |

| 1992 | Bolivia-Chile | Agreement on the Control, Monitoring and Repression of Illicit Drug Trafficking and Precursor Chemicals |

| 1998 | Bolivia-Paraguay | Memorandum of Understanding on the Control of Precursor and Essential Chemicals for the Production of Illicit Drugs |

| 1998 | Bolivia-Chile | Agreement on Mutual Cooperation for the Prevention and Control of Precursor and Essential Chemicals used for the Illicit Production of Controlled Substances |

| 1999 | Bolivia-Brazil | Agreement to Impede the Illegal Use of Precursor and Essential Chemicals for the Production of Controlled Substances |

| 2000 | Bolivia-Peru | Agreement on Alternative Development, Prevention, Rehabilitation, and Illicit Drug Traffic Control |

| 2000 | Bolivia-Argentina | Agreement on Alternative Development, Prevention, Rehabilitation, and Illicit Drug Traffic Control |

| 2001 | Bolivia-Colombia | Agreement on Alternative Development, Prevention, Rehabilitation, and Illicit Drug Traffic Control |

| 2001 | Bolivia-Brazil | Memorandum of Understanding between Financial Investigations Unit of Bolivia and Financial Activities Control of Brazil |

| 2004 | Bolivia-Colombia | Agreement on the Commercialization of Products from Alternative Development Programs |

| 2008 | Bolivia-Argentina | Memorandum of Understanding on Investigative Crimes (Drugs, Precursor Chemicals, Blank Capitals) and related crimes from a human rights perspective |

| 2009 | Bolivia-Brazil | Agreement between Country’s police departments for anti-narcotics operations |

| 2011 | Bolivia-Brazil | Agreement to exchange intelligence and strengthen joint police operations to combat drug trafficking |

| 2012 | Bolivia-Peru | Agreement to strengthen fight against drug trafficking |

| 2012 | Bolivia-Chile | Border control agreement with scanner use |

| 2012 | Bolivia-Ecuador | Agreement to strengthen fight against drug trafficking |

| 2014 | Bolivia-Peru | Agreement for intelligence exchange, improved airspace control, eradication, interdiction |

| 2015 | Bolivia-Colombia | Agreement to identify drug trafficking “big fish” through intelligence exchange and joint actions |

| 2015 | Bolivia-Peru | Security and Antinarcotics Agreement including training and collaboration between three branches of the two country’s militaries, focused on limiting air transshipment of drugs |

| 2015 | Bolivia-Paraguay | Reciprocal Agreement on Use Prevention and Repression of Illicit Trafficking |

| 2016 | Bolivia-Peru | Agreement on Cooperation for Alternative Development, Prevention, Rehabilitation, and Drug Trafficking Control |

| 2016 | Bolivia-Brazil | Agreement on Drugs and Related Crimes |

| 2016 | Bolivia-Argentina | Security and Anti-drug trafficking agreement |

[1] In the “Presidential Determination on Major Drug Transit or Major Illicit Drug Producing Countries for Fiscal Year 2017” the U.S. decertified Bolivia along with Myanmar and Venezuela. The Determination states that Bolivia “failed demonstrably during the previous 12 months to adhere to its obligations under international counternarcotics agreements.”

[2] AIN communication with US Embassy La Paz Public Affairs office. 11 August 2016.

[3] U.S. officials say that Operation Breakthrough, initiated in Bolivia in 1993, provides the baseline methodology to calculate potential cocaine production in the Andes. Yet current estimates, which reportedly continue to employ these methods, demonstrate some dramatic contradictions. The U.S. government complained in March 2012 that they have been unable to carry out yield studies in Bolivia since the expulsion of the DEA in January 2009. The 2015 INCSR says that the US uses cocaine originating in coca-producing coutnries, but admits it only has data from one Bolivian coca producing region. In other words, U.S. officials do not have the basic information needed to calculate potential cocaine production in Bolivia. For more information see:

https://www.wola.org/sites/default/files/AIN-WOLA%20Final%20Bolivia%20Coca%20Memo.pdf

[4] For more information on coca monitoring visit https://www.wola.org/sites/default/files/Drug%20Policy/WOLA-AIN%20Bolivia.FINAL.pdf

[5] Plan Estratégico, ENACO, S.A. pp 10-11.

[6] The UNODC report for Peru provides the conversion equation for potential cocaine production: 2,391 kg/ha (2.391 MT/ha). According to a 2013 Peruvian study, the amount of cocaine used for traditional consumption is 10,728 MT out of total potential cocaine production of 96,304 MT. To find cocaine deviated into illegal market: 96,304-10,728=MT, then divided by 2.391 MT/ha gives the result 35,791 hectares of coca deviated for illegal production.

[7] Although the majority of coca produced in the Chapare does not go through the Sacaba Wholesale market in outside Cochabamba, this does not mean it is all being deviated into cocaine production. Coca merchants and producers are reticent to travel 4-5 hours to Cochabamba, to register sales, and then return through the Chapare to more direct routes to sell coca to the Santa Cruz department (37% of all licit coca sales), Tarija Departments (16%). Chapare growers and international funders plan the construction of a checkpoint on the Chapare-Santa Cruz border to improve coca transport monitoring.

Bibliography

“Avionetas del narcotrafico investigadas por FELCN.” FM Bolivia. FM Bolivia, 2016. Web. 14 Sep. 2016 http://www.fmbolivia.com.bo/noticia177724-avionetas-del-narcotrafico-investigadas-por-felcn.html

Bajak, Frank. “Peru announces probe after AP drug plane report.” AP. Yahoo! News, 2015. Web. 20 Sep. 2016. https://www.yahoo.com/news/peru-announces-probe-ap-drug-plane-report-123919285.html?ref=gs

Beller, J. “Trilateral Project on Monitoring Coca.” United States Embassy in Bolivia. U.S. Embassy, 2012. Web. 14 Sep. 2012. https://bolivia.usembassy.gov/monitoringcoca2012.html

“Bolivia y Argentina coordinan acuerdo sobre seguridad.” El Pais. El Pais, 2016. Web. 14 Sep. 2016. http://www.elpaisonline.com/index.php/2013-01-15-14-16-26/nacional/item/228756-bolivia-y-argentina-coordinan-acuerdo-sobre-seguridad

Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs. International Narcotics Control Strategy Report. (Washington, D.C.: United States Department of State, 2014). Print.

Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs. International Narcotics Control Strategy Report. (Washington, D.C.: United States Department of State, 2015). Print.

Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs. International Narcotics Control Strategy Report. (Washington, D.C.: United States Department of State, 2016). Print.

“Colombia y Bolivia sellan acuerdo para identificar ‘peces gordos’ del narcotrafico. Pagina Siete. Pagina Siete, 2015. Web. 19 Sep. 2016. http://www.paginasiete.bo/nacional/2015/7/15/colombia-bolivia-sellan-acuerdo-para-identificar-peces-gordos-narcotrafico-63277.html

Charca, Roberto. “Brasil y Bolivia compartiran información.” La Prensa. La Prensa, 2013. Web. 14 Sep. 2016. http://www.laprensa.com.bo/diario/actualidad/seguridad/20130206/brasil-y-bolivia-compartiran-informacion_43136_69233.html

CONALTID. “Indice” Compromisos Internacionales de Bolivia en Contra de las Drogas: 1961-2010. (La Paz: Consejo Nacional de Lucha Contra el Trafico Ilicito de Drogas, 2010). Web. 14 Sep. 2016. http://www.gbv.de/dms/spk/iai/toc/688813097.pdf

Cuiza, Paulo. “Bolivia, Brasil y Peru crean un Centro de Inteligencia Policial para la lucha antidroga.” La Razon. La Razon, 2016. Web. 14 Sep. 2016. http://www.la-razon.com/nacional/seguridad_nacional/Bolivia-Brasil-Centro-Inteligencia-Policial_0_2518548134.html

“Dos de 14 Radares Serán Móviles y Servirán para Detectar Avionetas de ‘Narcos.’” Noticias Fides. Agencia Fides, 2016. Web. 20 Sep. 2016. http://www.noticiasfides.com/sociedad/dos-de-14-radares-seran-moviles-y-serviran-para-detectar-avionetas-de-narcos-369215/

Editor. “Bolivia y Paraguay suscriben acuerdo de cooperacion para la ejecucion de operaciones conjuntas antidroga.” Red Pais. Red Pais, 2015. Web. 14 Sep. 2016. http://redpaiss.com/es/22/sociedad/6309/Bolivia-y-Paraguay-suscriben-acuerdo-de-cooperaci%C3%B3n-para-la-ejecuci%C3%B3n-de-operaciones-conjuntas-antidroga-FELXN-BOLIVIA-PARAGUAY.htm

Editorial Board. “How Bolivia Fights the Drug Scourge.” The New York Times. The New York Times, 2016. Web. 20 Sep. 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/14/opinion/how-bolivia-fights-the-drug-scourge.html?_r=2#story-continues-1

“EEUU Informó a las Autoridades su Metodologia de MEdicion de Cocales.” Noticias Fides. Agencia Noticias Fides 2016. Web. 21 Sep. 2016. http://www.noticiasfides.com/politica/eeuu-informo-a-las-autoridades-su-metodologia-de-medicion-de-cocales-368641/

“El Director Ejecutivo Adjunto de la UNODC logró una productive mission en Bolivia.” UNODC. United Nations 2016. Web. 21 Sep. 2016. https://www.unodc.org/bolivia/es/El-Director-Ejecutivo-Adjunto-de-la-UNODC-logro-una-productiva-mision-en-Bolivia.html

Empresa Nacional de la Coca S.A. Plan Estrategico Institucional 2013-2017. (Cusco: ENACO, 2013). Web. 21 Sep. 2016. http://www.enaco.com.pe/files/pee13-17.pdf

“En frontera con Paraguay, policias decomisan 1.216 kilos de marihuana.” Pagina Siete. Pagina Seite, 2015. Web. 14 Sep. 2016. http://www.paginasiete.bo/nacional/2015/5/4/frontera-paraguay-policias-decomisan-1216-kilos-marihuana-55465.html

Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia, Ley 1008: Ley del Regimen de la Coca y Sustancias Controladas. 1988. Web. 20 Oct. 2015. https://www.oas.org/juridico/mla/en/bol/en_bol_1008.html

Estado Plurinacional de Bolivia. Ley de Seguridad y Defensa del Espacio Aereo (551) 2014. Web. 20 Sep. 2016. http://www.lexivox.org/norms/BO-L-N521.xhtml

Farfan, Williams. “FAB alista compra de escuadra de aviones para entrenamiento.” La Razon. La Razon, 2016. Web. 20 Sep. 2016. http://www.la-razon.com/index.php?_url=/nacional/seguridad_nacional/FFAA-FAB-compra-escuadra-aviones-entrenamiento_0_2456754397.html

Farthing, Linda and Kathryn Ledebur. Habeas Coca (New York: Open Society Foundations, 2015) Print.

“Informe de la UNODC: la destrucción de drogas incautadas en Bolivia en el primer semester de 2016 continúa realizandose con legalidad y transparencia.” UNODC. United Nations 2016. Web. 21 Sep. 2016. https://www.unodc.org/bolivia/es/informe-UNODC_Destruccion-de-drogas-incautadas-en-Bolivia-continua-realizandose-con-legalidad-y-transparencia.html

Instituto Nacional de Estadistica e Informática (Peru). “Resumen Ejecutivo.” Analisis de los Resultados de la Encuesta de Hogares sobre Demanda de la Hoja de Coca 2013. Web. 20 Sep. 2016. https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones_digitales/Est/Lib1286/PDF/resumen.pdf

International Narcotics Control Board. Report 2015. (Vienna: United Nations, 2016). Print.

“La OEA reconoce a Bolivia por sus avances en la lucha contra el narcotrafico.” La Razon. La Razon 2015. Web. 20 Sep. 2016. http://www.la-razon.com/index.php?_url=/nacional/OEA-reconoce-Bolivia-avances-narcotrafico_0_2252174831.html

“La Unión Europea se declara satisfecha y aplaude lucha antidroga en Bolivia.” Pagina Siete. Pagina Siete 2016. Web. 21 Sep. 2016. http://www.paginasiete.bo/seguridad/2016/9/20/union-europea-declara-satisfecha-aplaude-lucha-antidroga-bolivia-110520.html

Ledebur, Kathryn and Coletta A. Youngers. “Bolivia’s Historic Drop in Coca Cultivation Holds Steady.” Washington Office on Latin America. WOLA 2016. Web. 21 Sep. 2016. https://www.wola.org/analysis/bolivias-historic-drop-in-coca-cultivation-holds-steady/

Ledebur, Kathryn and Coletta A. Youngers. “Bolivian Drug Control Efforts: Genuine Progress, Daunting Challenges.” Washington Office on Latin America. WOLA 2012. Web. 20 Sep. 2016. https://www.wola.org/sites/default/files/AIN-WOLA%20Final%20Bolivia%20Coca%20Memo.pdf

Ledebur, Kathryn and Coletta A. Youngers. “Building on Progress: Bolivia Consolidates Achievements in Reducing Coca and Looks to Reform Decades-old Drug Law.” Washington Office on Latin America. WOLA 2015. Web. 21 Sep. 2016. https://www.wola.org/sites/default/files/Drug%20Policy/WOLA-AIN%20Bolivia.FINAL.pdf

Ledebur, Kathryn. “ONDCP Dramatically Downscales Potential Cocaine Production Estimates for Bolivia.” Andean Information Network. AIN-Bolivia 2016. Web. 21 Sep. 2016. http://ain-bolivia.org/2013/08/ondcp-dramatically-downscales-potential-cocaine-production-estimates-for-bolivia/

Ledebur, Kathryn. “Quantifying Chaos: ONDCP Cocaine Production Statistics.” Andean Information Network. AIN-Bolivia 2016. Web. 21 Sep. 2016. http://ain-bolivia.org/2016/08/quantifying-chaos-ondcp-cocaine-production-statistics/

“Limitaciones de Enaco generan Mercado paralelo de hoja de coca en Perú.” Gestión. Gestion Peru, 2015. Web. 20 Sep. 2016. http://gestion.pe/economia/limitaciones-enaco-generan-mercado-paralelo-hoja-coca-peru-2147569

“ONU felicita a Bolivia por la reducción continua de cultivos de coca.” Correo del Sur. Correo del Sur, 2015. Web. 14 Sep. 2016. https://correodelsur.com/seguridad/20150817_onu-felicita-a-bolivia-por-la-reduccion-continua-de-cultivos-de-coca.html

Organization of American States. The Drug Problem in the Americas. (Washington DC: Organization of American States, 2013) Print.

Programa de Apoyo al Control Social de la Producción de hoja de coca (PACS). Cultivamos con responsabilidad para cosechar un nuevo tiempo 2008-2013. (La Paz: Viceministerio de Defensa Social y Sustancias Controladas, 2013). Print.

Pereyra, Omar. “Encuentro: Bolivia y Argentina fortalecen lucha antidroga.” Eju tv. Eju! 2016. Web. 19 Sep. 2016. http://eju.tv/2016/09/encuentro-bolivia-y-argentina-fortalecen-lucha-antidroga/

President Barack Obama Memorandum of Justification for Major Illicit Drug Transit or Producing Countries for Fiscal Year 2017. (Washington, D.C.: United States White House, 2016). Print.

Quispe, Aline. “China entre escáner para control aduanero.” La Razón. La Razón 2012. Web. 21 Sep. 2016. http://www.la-razon.com/index.php?_url=%2Feconomia%2FChina-entrega-escaner-control-aduanero_0_1589841034.html

“Republica Dominicana: Celac analiza la problematica mundial de las drogas y los efectos en la salud.” Noticias de America Latina y el Caribe. NODAL 2016. Web. 20 Sep. 2016. http://www.nodal.am/2016/03/republica-dominicana-celac-analiza-la-problematica-mundial-de-las-drogas-y-los-efectos-en-la-salud/

“Thales Signs Historic Contract to Secure Bolivian Airspace.” Thales. Thales Group, 2016. Web. 14 Sep. 2016. https://www.thalesgroup.com/en/worldwide/aerospace/press-release/thales-signs-historic-contract-secure-bolivian-airspace

“Unasur trabaja en plan de acción en lucha contra las drogas.” El Espectador. El Espectador 2016. Web. 20 Sep. 2016. http://www.elespectador.com/noticias/elmundo/unasur-trabaja-plan-de-accion-lucha-contra-drogas-articulo-617579

Unión Europea felicita a Bolivia por la reduccion de cultivos de coca.” Eju tv. Eju! 2015. Web. 14 Sep. 2016 http://eju.tv/2015/08/union-europea-felicita-a-bolivia-por-la-reduccion-de-cultivos-de-coca-en-2014/

United Nations Development Programme. Reflections on Drug Policy and its Impact on Human Development: Innovative Approaches. (New York: United Nations Development Programme, 2016) Print.

“Unodc entrega hornos para incinerar droga.” La Patria. La Patria 2013. Web. 21 Sep. 2016. http://www.lapatriaenlinea.com/index.php/somos-noticias.html%3Ft%3Del-dia-de-la-mujer-boliviana%26nota%3D44370?nota=143634

“Unodc expandirá ayuda en Bolivia a tres áreas.” El Deber. El Deber, 2016. Web. 20 Sep. 2016. http://www.eldeber.com.bo/bolivia/unodoc-expandira-ayuda-bolivia-tres.html

UNODC, Bolivia: Monitoreo de Cultivos de Coca 2015. (Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2016). Print.

UNODC, Colombia: Monitoreo de territories afectados por cultivos ilicitos 2015. (Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2016). Print.

UNODC, Peru: Monitoreo de Cultivos de Coca 2015. (Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2016). Print.

Watson, Peter. “Peru y Bolivia coordinarán el control del espacio aereo para combater al narcotrafico.” Info Defensa. InfoDefensa, 2015. Web. 19 Sep. 2016. http://www.infodefensa.com/latam/2015/06/27/noticia-bolivia-coordinaran-control-espacio-aereo-combatir-narcotrafico.html