As the presidential campaigns gain momentum, AIN outlines the political and social landscape in Bolivia to provide background to understand upcoming electoral debates.

President Evo Morales is running for a third term in the October 12, 2014 elections. Critics argue he is not eligible to run for another consecutive term, but the Plurinational Constitutional Tribunal ruled in his favor, and the opposition across the political spectrum lacks a strong, unifying candidate. Four candidates have formally registered to run against Morales.

Bolivian Government Achievements

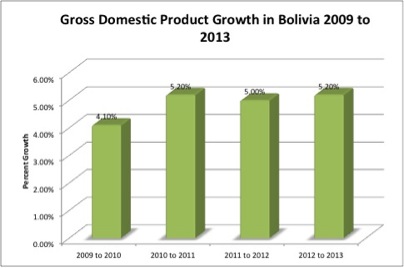

- Macroeconomic success:

- From 2009 to 2013, Bolivia’s economy experienced steady growth.

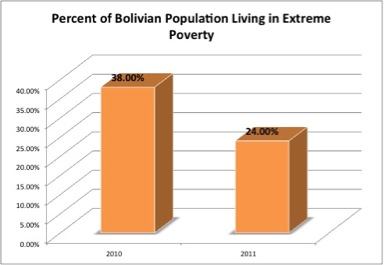

The population living in extreme poverty fell from 38% in 2005 to 24% in 2011.

- Bolivia has accrued a significant “rainy day fund.” According to the New York Times, “Bolivia has the highest ratio in the world of international reserves to the size of its economy, having recently surpassed China.”

- Employment rates and wages have both steadily increased under Morales. The minimum wage increased in 2013 from about $145 USD (1,000Bs) to about $174 USD (1,200Bs) a month.

- Double holiday bonus: In November 2013, President Evo Morales decreed that all employers must pay a double holiday bonus to all employees. Previously, the bonus was one month’s salary paid in December. The double holiday bonushad a mixed reception, celebrated by workers, but criticized by many employers and small business owners.

- Social programs: The Morales administration started several popular cash transfer programs, including benefits to school children and pregnant mothers, which have promoted significant decreases in maternal and infant mortality as well as increases in school attendance and high school graduation.

- Gas income: The Bolivian government has strengthened the economy by increasing state hydrocarbons revenues as a result of the 2004 hydocarbons law, the 2006 Nationalization Decree, and high gas prices. This income has permitted significant investment in infrastructure and social programs.

Coca Leaf and Drug Control

- In 2013, Bolivia successfully petitioned the United Nations to recognize legal coca cultivation and uses within its borders.

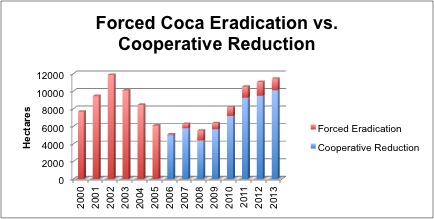

- The Morales administration has achieved sustained reductions in the cultivation of illicit coca leaf using a system of community coca control. (26% reduction from 2010-2013).

- Unlike previous military forced eradication, this innovative model relies on coca grower participation. This model guarantees subsistence and enables coca growers to diversify their income, leading to greatly reduced human rights violations. For more information see this WOLA-AIN memo.

Source: Bolivian Vice-Ministry of Social Defense

- Bolivia currently has less than half as much coca as Colombia and Peru. Yet inexpensive and abundant Peruvian cocaine paste base floods through Bolivia to Brazil and other consumer countries, offsetting national control efforts.

- The Morales’ administration has diligently pursued drug interdiction after the 2009 expulsion of the US Drug Enforcement Agency, reporting significantly increased seizures. However, the great bulk of cocaine sales and profits trafficking occur outside Bolivia’s border, limiting the impact of these initiatives.

- In spite of tensions, US-Bolivian on-the-ground collaboration on coca reduction continued productively until September 2013, including a trilateral agreement, including Brazil, to improve monitoring technology.

Challenges facing the Morales Administration

- TIPNIS issue: In spite of much rhetoric about protecting the rights of Mother Earth, the Morales administration has gone ahead with plans to build a highway through the Amazon, including the TIPNIS, a national park and indigenous territory.

- This is an enduring point of contention in the country, most notably among lowland indigenous peoples who led two marches to La Paz to protest the lack of prior consultation of TIPNIS resident about the project, which is guaranteed by the 2009 Bolivian constitution. Both marches, in 2011 and 2012, were met with police repression from the government. The segment of the construction project within the territory is on hold, but may be resumed. Critics highlighted contradictions with the administration’s pro-indigenous and environmental discourse and its handling of the incident.

- The lowland indigenous umbrella organization, CIDOB, and its highland counterpart CONAMAQ are both split between factions that support the MAS ruling party and its vocal opponents.

- Policies of extraction vs. environment: One of the most significant challenges for the MAS administration has been balancing multi-sector demands for basic services financed primarily by extractive industries with its rhetoric of protecting and living in harmony with nature.

- Bolivia’s economy has always been heavily reliant on extractive industries such as mining and hydrocarbons that have a substantial environmental impact. Conflicts often arise in mining communities over the benefits of mining income versus the damage to the environment. In addition, continuing contamination, such as the recent bursting of a damn holding toxic mining tailings in the Chuquisaca department, exacerbates the Morales administration’s inherited legacy of environmental degradations from centuries of mineral exploitation.

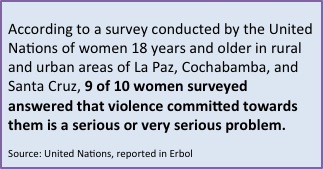

- Violence Against Women: Violence against women and children has always been startlingly prevalent in Bolivia. In March 2013, the Bolivian Congress passed a comprehensive a law to address these issues, which contained progressive ideas and preventative measures. However, the government lacks the resources and political will to fully implement the law. See this AIN update for more information.

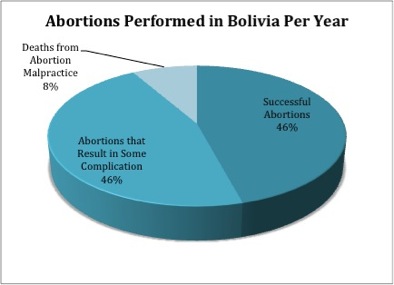

- Unsafe abortions: This is another concern for women in Bolivia. Abortions are illegal except in the case of incest, rape, or if the mother’s life is in danger. Pro-choice advocates had a partial victory in a February 2014 constitutional tribunal ruling that upheld the illegality of abortion, but threw out the rule that requires women to get a judge’s consent in the three permitted exceptions. (See Emily Achtenberg’s article in NACLA for more information on this ruling.) Lack of access to and information about sexual and reproductive health combined with cultural taboos and widespread sexual violence put women’s health at risk and severely limit their choices. Although they are illegal, an estimated 60,000 abortions are performed in Bolivia each year, and only 46% of them are performed without complication. See this AIN update for more information.

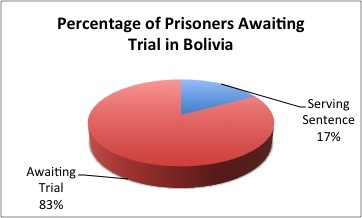

- Judicial delay and prison overcrowding: The Bolivian justice system suffers from tremendous judicial delay, resulting in lengthy pretrial detention, as well as severe prison overcrowding. Only 17% of prisoners in Bolivia are actually serving their sentence, while the other 83% are merely awaiting trial, which could take years. After prison riot and fire that killed 35 people, Morales a pardon and amnesty decree in September 2013. However, to date the pardon has benefitted only about 800 people. More comprehensive reforms, including the reduction of disproportionately high drug sentences (drug war prisoners make up almost half of all inmates) need to be enacted.

Source: La Opinión

- Legacy of dictatorships: Unlike neighboring Chile and Argentina, which initiated some legal action against those involved, impunity for authors of human rights violations continues in Bolivia. A group of survivors of the dictatorship have maintained a vigil for more than two years outside the Ministry of Justice, demanding acknowledgment for the crimes of the dictatorship and the declassification of military files from the dictatorship era. In 2004, the Bolivian government passed a law guaranteeing compensation to victims, but modifications have reduced the initial promised aid to 20%, and only 1,714 of the 8,000 who applied were approved to receive benefits. See this AIN update for more information, as well as this Amnesty International report and BBC article.

Photo: Gonzalo Ordoñez for AIN

Bolivian-US Bilateral Relations

- A mutual lack of trust is the single largest impediment to improved bilateral relations. This lack of confidence should be addressed as a prerequisite for reinstatement of ambassadors. In spite of a lack of ambassadors, bilateral relations have varied, depending on the skill of the Chargés and other officials from both nations.

- A lack of transparency on the part of USAID and credible allegations that the agency was inappropriately aiding lowland opposition led Morales to expel Ambassador Goldberg in 2008. USAID in Bolivia did not follow international agreements on development. See AIN background.

- The Morales administration responds positively to genuine diplomatic gestures. For example, November 2008 meetings with US congressional leaders permitted the sort of frank exchanges that can create rapport and lay the basis for more regular dialogue and better mutual understanding. See WOLA and AIN analysis on bilateral relations.

- US decisions to “decertify” Bolivian drug control efforts since 2008 are increasingly disconnected from reality. Governments in the region continue to see the US determinations as offensive and politically motivated. More information here.

- US funding steadily decreased since 2008. Although the Narcotics Affairs Section, the Drug Enforcement Agency, and USAID are now gone, Bolivia has compensated with funds from its own treasury and increased support from the European Union.

- Request for extradition of ex-President Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada: Widespread resentment continues for the US refusal to extradite the ex-president for the death of 69 protestors in October 2003. Although US officials claim the charges are politically motivated, two-thirds of the Bolivian congress, where Sánchez de Lozada’s own coalition had a majority, voted to indict him. The Bolivian government submitted a new extradition request on July 10th, 2014 and the US has promised to respond within sixty days. The US is expected to reject this initiative.

- US citizen Jacob Ostreicher accused of money laundering: Although US representatives and Sean Penn have argued for Ostreicher’s innocence, charges against Ostreicher appear credible. He was subject to protracted pre-trial detention in violation of his due process rights, as is every Bolivian arrested on drug charges under drug legislation imposed by the US in 1988. There was also a great deal of corruption around his case on the part of some Bolivian government officials. He escaped from Bolivia at the end of 2013 and is considered a fugitive by Interpol.

Conclusion

Recurring protests and strikes from diverse sectors, including transportation workers, university students, and milk and meat producers have characterized the political and social landscape in the past few months. However, this does not necessarily equate to discontent with the Morales administration. Rather, many sectors are strategically taking advantage of election momentum to leverage to get demands met. As one indigenous protester explained, “We’re not the opposition. We just want the respect of our people and our rights and a solution.”

Although the administration’s performance has been mixed, Morales still enjoys widespread support and his party will most likely retain a majority in both houses of congress. Furthermore, the opposition on both the left and the right lack a strong, representative, unifying candidate. It is likely that Bolivian voters will opt for continuing the status quo.